Malta’s 1921 Constitution: A Colonial Compromise

The 1921 self-government constitution was presented as a milestone in Maltese political development, but in reality, it was a strategic tool used by the British Empire to maintain control over their Mediterranean stronghold during the interwar period.

From the British perspective, granting political concessions to the Maltese elite helped placate local demands for autonomy while safeguarding imperial interests at a time when traditional empires were under pressure globally.

Early British Rule and the Quest for Control

When the British expelled Napoleon’s forces from Malta in 1800, it was widely expected that they would act as protectors rather than rulers. Initially, the Maltese trusted the British to preserve their traditional privileges, the authority of the Catholic Church, and local autonomy.

However, under Governor Sir Thomas Maitland, appointed in 1813, Britain formally established Malta as a crown colony to secure a strategic naval base in the Mediterranean. Early British administrators viewed the Maltese elite as inexperienced and unfit for governance.

The 1812 Royal Commission bluntly stated that no people on earth were less suited to political office, and it was in Malta’s best interest that the population had no real political authority.

The Gradual, Limited Introduction of Local Representation

The first sort of local representation granted by the British since their arrival to Maltese shores was when they granted the 1835 constitution which saw three Maltese unofficial members appointed to the council of government by the governor. So in reality, it wasn’t a total local representation since the governor chose pro-British representation.

The British kept politicians at a distance, arguing that they represented only themselves, while securing the loyalty of the population through strong ties with the Church, whose influence over the people they keenly recognised.

Nevertheless, Maltese politicians remained persistent, though their efforts were met with reluctant, incremental constitutional concessions: in 1835, a consultative Council of Government; in 1849, limited representation; in 1864, partial control over fiscal matters concerning purely local affairs; and in 1887, majority representation with restricted responsibilities.

Essentially, the British granted Malta illusory constitutions and then withdrawing them as soon as the Maltese attempted to use their power in any way that did not approve to the British.

Maltese Demands for Self-Government

By the early 20th century, the Maltese political elite were increasingly assertive. The Assemblea Nazionale, formed by local politicians, held its first session on 25th February 1919, demanding “full political and administrative autonomy in affairs of local nature and interest.”

These demands echoed international developments. US President Woodrow Wilson’s post-World War I program emphasised self-determination as a guiding principle for nations. Maltese politicians referenced Wilson’s ideas and King George V’s support for national rights to strengthen their case.

The Maltese drafted a constitution calling for leaders to be chosen through party-based elections. The British opposed this but proposed a diarchical system, modelled after a system tested in India, to appease local demands without relinquishing real control.

The 1921 Self-Government Constitution

The “self-government” constitution saw an increase of Maltese politicians in the council of government. In 1921 there were 10 Maltese (Six elected by a limited electorate and four nominated by the governor) politicians in government. This increase of number harks back to the granting of the 1887 constitution in which 14 Maltese members were allowed.

The constitution strengthened the sense of nationhood, made local politicians directly accountable for promoting the common good and highlighted the limitations faced by Maltese representatives living within a fortress colony. It inspired politicians to envision, and eventually work toward, reducing Malta’s colonial dependence through constitutional progress.

In comparison with previous constitutions, like that of the 1903 “Chamberlain” constitution, the 1921 gave more representation in the council of government.

1921 constitution revoked

By 1930-1933, political tensions escalated because of three reasons. The first being religion and education which saw a fierce clash between the Constitutional Party (which was pro-British and liberal) and the Nationalist Patrty (which was Catholic and very Italian-oriented). Secondly, the Catholic Church issued pastoral letters forbidding Catholics from voting for Constitutional Party candidates. This created a constitutional crisis, as elections were disrupted. Finally, the British governor at the time suspended the self-government constitution over these conflicts.

In 1933, the constitution was formally revoked after another Nationalist electoral victory. The British authorities accused the Nationalist government of promoting Italian language and culture at the expense of English, which was seen as dangerous given Mussolini’s rise and Italy’s claims over Malta.

Thus, one can conclude that the self-government constitution granted in 1921 by the British to the Maltese politicians meant that they were giving illusory concessions just to then revoke them as soon as some trouble emerged.

Malta didn’t regain self-government until after the Second World War, in 1947, which saw a 14-year gap which saw the British gaining more control over their colony while there was the local instability and while they had to give priority to the defence of their island fortress throughout the Second World War.

Thus, while the 1921 was definitely a huge achievement for the Maltese politicians to develop themselves and pave the way for Malta’s political future, it was ultimately, a colonial compromise giving the illusion that some power is being leased to the Maltese and later pulled back as soon as there was a hint of anti-British sentiment or instability in the local arena.

Do you think incremental political concessions helped or hindered the long-term goal of independence?

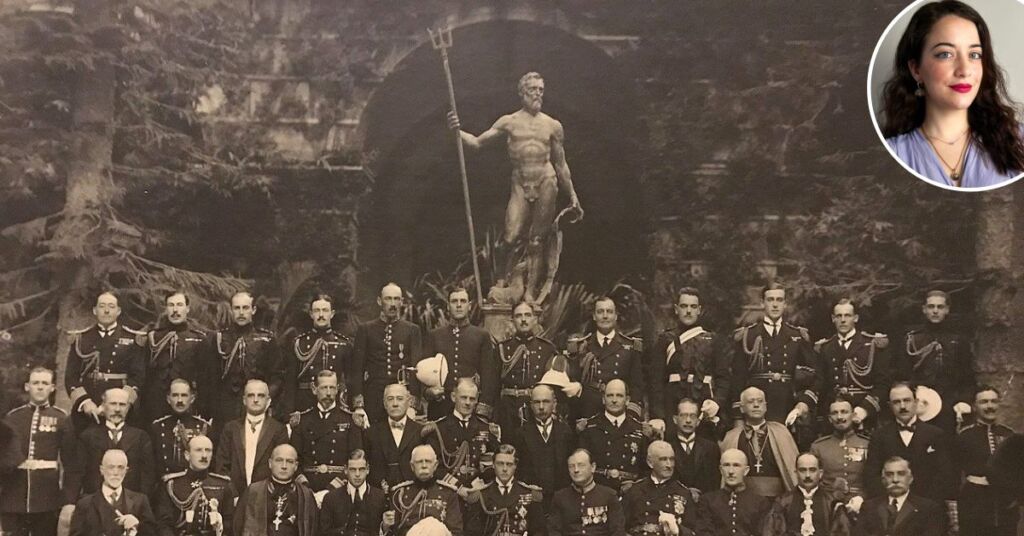

Featured image: Richard Ellis Archive