MALTESE HERSTORY: Malta’s First Established Female Painter Was A Bold, Baroque And Free-Roaming Nun

Whether you’re a local or floating tourist – you’re bound to come across the ornate paintings of the Baroque master Mattia Preti. And while he is rightly put on a pedestal in Maltese art history, a closer look at his bottega reveals another jewel – Maria De Dominici – sculptor, tertiary nun and the first established female painter recorded in Malta.

Introducing Maria De Dominici: free-roaming nun, painter and unbeknownst feminist

An artistic interpretation of Suor Maria de Dominici, from L'Arte 1-51

Suor Maria De Dominici was born today, December 6th, in 1645 in Vittoriosa to a gifted Napolitan family of artist and goldsmiths.

She is known for her association with famous Baroque painter Mattia Preti – responsible for some of the greatest artworks on the island, including the ethereal paintings on the vaulted ceilings of St. John’s Co-Cathedral. She was even said to have contributed to Preti’s cathedral work, though she was often glorified because she was a nun and female painter.

Unlike other female painters of the time, who were often overlooked for their gender, De Dominici held a respected reputation and is the most well-known painter in Pretti’s renowned art studio, where she worked with her two brothers Raimondo and Francesco.

St. John's Co-Cathedral

De Dominici was set on breaking boundaries for women

As a tertiary nun and pinzocchera, De Domenici took vows of chastity and obedience but was not confined to a religious convent and free from ties of contrasts of family ties.

De Dominici ripped up the idea of what 17th Century women were expected to do – that is – submit to their husbands and tend to housework and children.

She worked as a painter for Preti, as an independent artist in her own right and as a sculptor, earning commissions and living independently in Malta and later in Rome, where she died.

Biographies of the nun described her as a fiery woman – strong-minded, stubborn and bold. The 18th-century Maltese historian Giovannantonio Ciantar described her as wanting more than the traditional norms that come with being a Baroque woman:

“[Maria showed a] repugnance to apply her energies to female duties and was thus often rebuked by her parents … She would do nothing other than draw figures and other things according to her whim and natural talents. At last her parents, seeing her so inclined and disposed to painting, providing an art master to teach her design.”

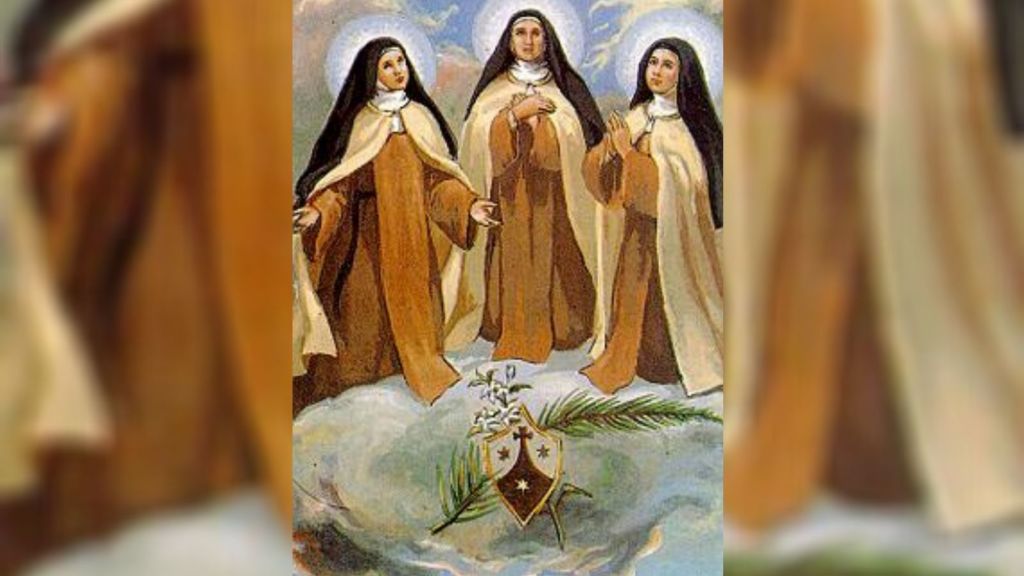

The Carmelite Martyrs of Guadalajara, Spain

Perhaps it is why she turned to religion – to dedicate her life to her work.

Her surviving works

Beyond her work in Preti’s art studio, only six of De Dominici’s works are known to survive.

Research by Maltese art historian Nadette Xuereb, professional photographer Joe Borg and the Head of the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Malta, Professor Keith Sciberras, shows that these are all religious works: three altarpieces and three smaller works.

They are all characterised by her distinctive style, the use of subdued pastel colours, soft bodies and angular folds and drapery. They can all be found scattered across the island.

From right: Vision of St Maria Maddalena de Pazzi, St Teresa of Avila and Visitation of the Virgin

Virgin with St. Nicholas and St. Roque can be found in Attard and is her only documented work. In the Carmelite Priory in Valletta, there’s her painting of Christ Receiving St Maddalena de Pazzi.

Then there is her Visitation of the Virgin, which was heavily repainted and lives at the old sacristy in Żebbuġ Parish Church. It was supposed to be the altarpiece for the Chapel of the Visitation at Wied Qirda in Żebbug together with two side paintings of St Teresa of Avila and St John of the Cross, which are kept in the parish’s storage.

Lastly, there is a small Crucifixion with Saints, in a private collection which was recently been ascribed to her.

While these are the only works confirmed to form part of her oeuvre, there should be other works not yet discovered, amended or even destroyed.

Historians also say De Dominici was even more gifted as a sculptor. She produced a number of portable statues of saints for religious street precessions and is rumoured to have left to Rome to pursue the art form, encouraged by her painting master Mattia Preti.

Photograph of the Immaculate Conception sculpture by Maria de Dominici, with the original pedestal

Unfortunately, none of her sculptures survives except for a heavily amended Immaculate Conception, found in Cospicua parish church.

Even as a pioneer, it wasn’t easy as a female artist

Female artists in 16th and 17th Century Western Europe dealt with countless social, educational and political barriers in the face of becoming great masters of their craft.

Gerard Terborch (Dutch Baroque Era Painter, 1617-1681) Woman Writing a Letter, 1655

Despite the unconventional life lived by the out-of-convent nun and painter, De Dominici was also very aware of the double standards she faced. In fact, in her two wills penned in Rome, she describes being underpaid for her work.

Her gender may have been the most defining hurdle in her life.

Women at the time weren’t allowed to study male anatomy, which could be the reason why her figures were more feminine and less defined than her male counterparts.

Perhaps, if she were allowed to hone her skills, she could have flourished even more as an artist. She also died middle-aged, at just 57 years old, hindering her ability to produce a large body of work and perhaps to mature into a master painter.

Her legacy lives on

Chapel of the Visitation at Wied Qirda by Joe Borg

While De Dominici’s work was not particularly exceptional, she is the most well-known painter from Mattia Preti’s bottega, and plays an engrossing role in history: helping Preti prepare his oeuvres at St. John’s Co-Cathedral, her own independent paintings and sculptures and of course, as the first female artist on this little island.

Today, her legacy lives on. De Dominici continues to be studied and admired for breaking ceilings for local female artists and in Western history of art. In 2010, a crater on Mercury was named after her. In Malta, a street in Santa Lucija is named after her too.

If we can learn anything from Suor Maria De Dominici, it’s that stubbornness in the face of claustrophobic ideas of gender are worth fighting. We may not shatter the entire ceiling single-handedly, but if we all chip away at it, it’ll come crashing down faster.

Special thanks to Prof. Keith Scibberas, who attributed the works of art based on the only documented work of Suor Maria De Dominici in Attard.

Special thanks also goes to Nadette Xuereb. Her research on the scholarship and life of De Domenici, together with Joe Borg, made this article possible. You can read her BA (Honours) in History of Art’s thesis here.

A previous version of this article stated that De Dominici aided Mattia Pretti with the preparatory work at St. John’s Co-Cathedral, as claimed by some biographers. However, recent scholarship shows because she was a nun and female artist, her contributions were often glorified.

Tag someone who needs to learn about Maria De Domenici!