Watch: ‘They Told Me If I Slept At Night, I’d Be Raped To Death’ – Human Trafficking Survivor Shares Her Harrowing Story

After being promised a flight to Europe, Precious found herself crossing three West African countries before arriving in Libya, catching a boat to Italy and waking up in Malta eight years ago.

“I fell for the same trick that every lady does when they leave home,” Precious told Lovin Malta in an exclusive interview.

However, she found herself in Burkina Faso and that was the start of what would become a two-year journey to Malta.

Now 31 years old, Precious sat down with Lovin Malta as part of a larger campaign led by TAMA wherein we interviewed six people who sought refuge in Malta and have either witnessed or experienced horrific sexual gender-based violence while migrating.

Life in Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso

Precious arrived in Burkina Faso in 2015 at just 21 years old with the smugglers’ intent to force her into prostitution. However, the woman who was running the brothel thought Precious looked too young so she sent her to work with her sister in the village.

She explained that she was lucky because in many cases, which she had already witnessed, people who weren’t forced into prostitution by one trafficker would just be sold to another.

The sister in the village took care of Precious, but after a while, she fled back to the city where she stayed with Nigerian women.

“Some were nice, but others were horrible to me,” Precious explained.

This was the first time she had ever left Nigeria and many of the women around her were Yoruba who spoke a French dialect which, at that point, she couldn’t understand. While she didn’t divulge much, it was clear – for obvious reasons – that this transition was incredibly difficult for Precious.

As time passed, the language barrier prevented her from integrating and at some point, she became a “burden” to these women. So, as two women decided they would travel to Ivory Coast, the others, in French, told them to take Precious with them.

Of course, Precious was confused. She went with them but didn’t realise until two days later that she was in another country. She only figured out she had crossed borders because she took note of the change in lifestyle residents were leading.

She explained that the people in Burkina Faso lived extravagantly while those in the Ivory Coast are more frugal and similar to Nigerians. Corruption within the police force was another clue that she was no longer in Burkina Faso because there, “they don’t accept bribes”.

Life in Ivory Coast

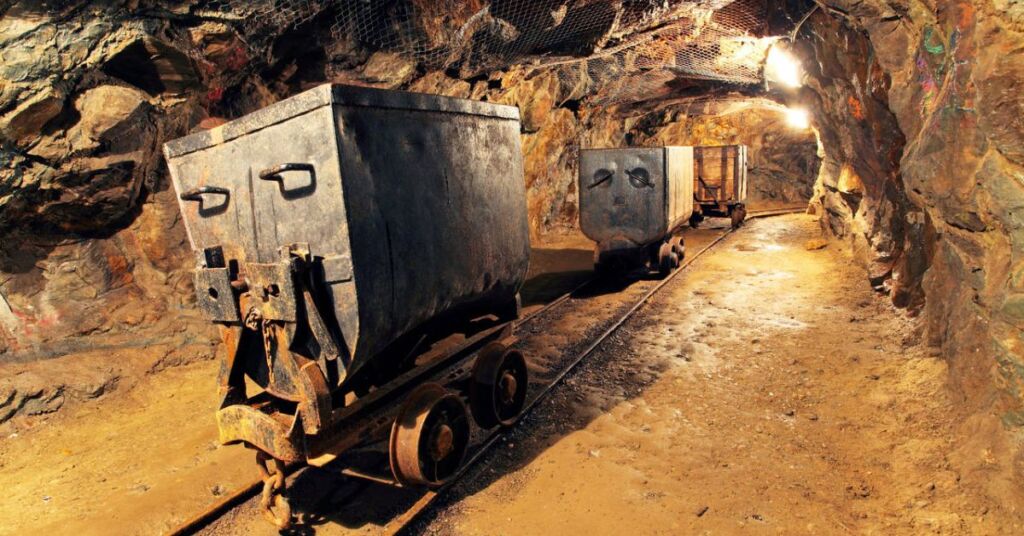

Gold mine in Ivory Coast: TTstudio | Shutterstock

Life in Ivory Coast was better. Precious began to learn French and she met other Nigerians who showed her how to make a living.

She didn’t earn as much as she did in Burkina Faso, where she said that she worked less but was given money by people who liked to “show off”. Overall, she was able to get by in Ivory Coast, but not without hardship.

“I had to struggle in Ivory Coast; everyone is struggling there.”

For work, Precious would go into the bush with villagers to help them dig for gold. There were no homes or buildings so she built a structure made of plastic as shelter in the nights.

As a woman, she wasn’t allowed to go into the mines and dig, her role was to pass on the gold to the machines which frustrated her because “the men were lazy”.

She did this for six months and made very little money because people would buy the plot and the miners would be forced to sell the gold to the owner according to the owner’s price. This means they got a fraction of what both the work and the gold were worth.

A whole day’s work would give her something between 0.15 cents to 0.30 cents.

“It was extremely hard.”

Precious managed to save up some money and she travelled with some friends to Mali.

Life in Mali

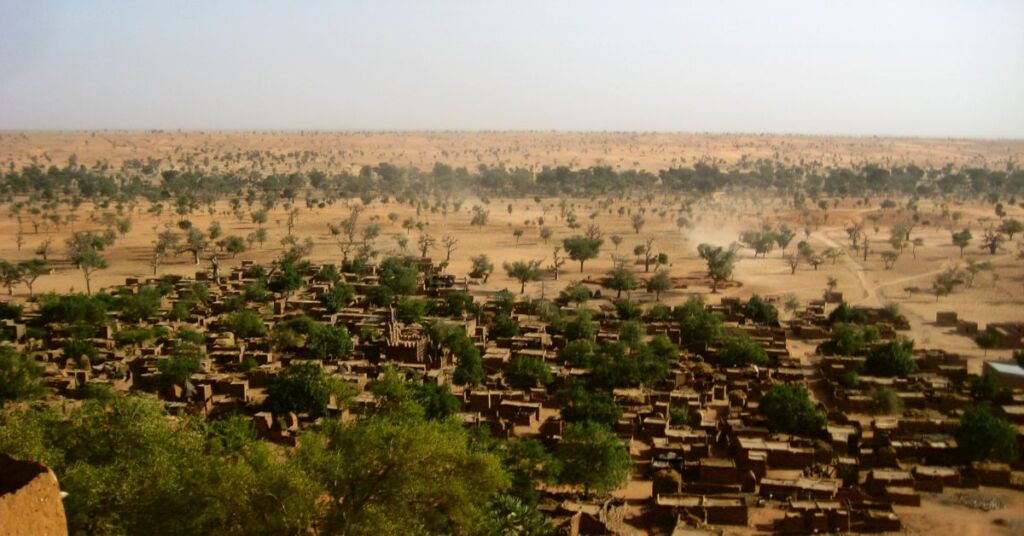

Mali

“In less than six months in Mali, we became the bosses of the place.”

In Mali, Precious was able to dig gold on her own and she made a lot of money doing it. It was hard work but without the intervention of a middleman, Precious was earning much more.

Eventually, she fell pregnant and that’s when she decided to leave again.

Mali sorely lacked healthcare infrastructure: there was no hospital, no doctor – and having already seen people give birth in Mali, Precious instantly knew that she could not take that risk.

To make matters worse, people around her started began ousting and mocking her because she was pregnant.

“People took it against me because I didn’t want to be a prostitute and I wasn’t married, yet I got pregnant. They assumed I thought I was better than them.”

That being said, Precious would have left Mali if she hadn’t got pregnant, but she would have likely stayed in West Africa. Her initial plan was to go back to the Ivory Coast where she was already renting an apartment but the pregnancy pushed her to venture to Europe in search of a better life for both herself and her child.

That was how her journey to Libya started.

The long road to Libya

Sahara Desert

Precious and her ex-partner – who is the father of her child – left one city in Mali and travelled to Algeria, stopping at different cities on the way.

The trouble started when they arrived in Kidal – located in the desert region of northern Mali – in the midst of a civil war. Women were going missing and danger was looming, so smugglers packed some 200 migrants into one truck and started driving out: “Everyone was throwing up on each other,” Precious recounted.

They were driving from one checkpoint to another where people would be searched and money was stolen by the military and insurgency groups. It came to a point where people started giving Precious their money because her condition as a pregnant woman made her less likely to be searched.

When the truck finally arrived in Algeria, everyone instantly began running into the desert because they knew what was waiting for them if they didn’t. However, Precious and her ex-partner had no idea what was happening – someone even dragged Precious to run with her but the father of her child wanted a cigarette, so he entered a gate close by to ask for one and she followed.

“That was where the trouble started. That place he entered is a no-go area.”

The smugglers – who operate the truck – inform traffickers that a truckload of people will be arriving outside their sites. From there, people are either captured or unknowingly walk in and their only way out is money.

“Anything can happen there. You can enter that building and never come back,” Precious explained.

When Precious got in, she saw a woman who warned her to find a way to get money and get out; she gave her a small, sharp knife for protection which Precious used twice throughout the journey. Later that night, a man who they had travelled with was hung upside down because he had no money.

Two women then took it in turn to make sure Precious didn’t sleep at night because if she did, she could’ve easily never woken up again.

“They told me that if you sleep at night you could either wake up somewhere else or get raped to death,” Precious recounted.

She stayed awake all night and the next morning her partner sold their phones and they were let out and taken to another one of the traffickers’ quarters just a few metres away: “It was even worse than the first one.”

A lot of the women there looked comfortable and well taken care of but had been living there for three years. This terrified Precious, who knew that they were being fed empty promises; they’d do the house chores and have sex on request with the men in charge of the place, but would remain captive in these quarters.

At one point, Precious was asked to go and take a shower but she felt a bit suspicious about it all, she tried to refuse but they didn’t want to let her out of the apartment they took her to. So she brought out her knife and slashed one of them, managing to run out unscathed.

When she made it out, she instantly called her family to ask them for money to get her out of there. They transferred something between 50,000 to 100,000 algerian dinar (around €400 to €700), but that wasn’t enough for the traffickers. Precious called her family again and after around three days they sent the money that set her free. To this day, Precious doesn’t know how much they spent to save her.

After those few days, she was told she’d be travelling to Tamanrasset in the evening. This would be her final stop before Libya, they said.

She was crammed into a filled bus and once the night started fading away, everyone was discharged from the bus and it turned back. They were left completely alone in the desert with no idea of where they were.

After a while of walking, the migrants stopped a truck that was passing and asked where they were. They were nowhere close to Tamanrasset and the nearest village was 150 kilometres away. Upon hearing this, one of the migrants collapsed; “That was the end of him.”

Precious’ partner took the water from his body and they began their journey on foot.

“You can’t look back.”

At this point, Precious was three months pregnant; the nausea, vomiting and fatigue had gotten much worse. Not to mention that she hadn’t eaten the whole day before travelling out of the quarters and had very little food on her.

Eventually, they saw another van pass and the driver offered them ride, but her instincts said it wasn’t safe. Her partner was constantly complaining; “He was acting worse than a toddler”, Precious explained. She had to give him all of her food and still, he decided to give these people the money all they had left.

They got on the van, were driven around for around three minutes, were kicked off the vehicle and it sped away.

“They were members of the mafia; they took our money and drove around in circles, we were still 150 kilometres away. We had no money, we had no water – we were stuck.”

Their only choice was to keep walking.

After a whole day, they found some farmers who allowed them on the truck and got them to the nearest village. They stayed in an unfinished building near the farmers’ home for around three months, they gave her some work in their home and after some time they managed to get to Tamanrasset by bus.

Precious was able to get a job but she had to walk an hour to and from every single day because black people weren’t allowed in taxis in the city unless they paid five times the amount.

After some time, they travelled to another city and that’s where she realised that women crossing to Libya have it a lot worse than men.

“My own black brothers who gave us a place to stay tried to rape me multiple times while I was pregnant.”

Overall, Precious spent six months travelling from one Algerian village to another before she got to Libya. When she had finally reached Debdeb – the boundary to Libya, she was raped – while heavily pregnant – by a Libyan man.

In Debdeb, Precious met the same woman who gave her advice and a knife six months earlier, however, despite working for the traffickers for years, she was penniless. They never paid her a cent and Precious instantly knew that that could have been her had she not managed to flee.

While at the border she needed to make money for transportation to Libya. So, she and the woman she knew began converting money from Algerian dinar to Libyan dinar and were making money from the exchange. Precious also began interpreting and buying and reselling condoms and other products for prostitutes who didn’t speak any French. She also found men for them who also gave her some commission. Eventually, Precious managed to scrape up enough money to get on a bus to Libya.

“From that night, harassment started.”

As a woman travelling between Debdeb to Libya, you have two options: have sex with the multiple men who harass you or fight, Precious explained.

“It depends on how many men you’re facing and how aggressive they are. This happened to me multiple times but there’s a limit to what I could bear as a human.”

She saw young teenagers bleeding from rape and forced abortions and she was helpless otherwise that, or worse, would have happened to her.

“You see the male migrants and nothing happens to them… nothing.”

Connecting the Dots: Migration, Gender Justice and EU Solidarity

This interview is part of a series being released in the lead-up to an event organised by local NGO TAMA Connecting the Dots: Migration, Gender Justice and EU Solidarity.

It’s a completely free event taking place on 24th May where people will be sharing their stories of gender-based violence during the migration process. The event will feature panels, film screenings and a variety of workshops intended to shed light on what it takes to seek refuge in Europe.

“An event like this should take place every year,” Precious said.

“When I say I’m sharing my story, I’m just sharing the surface of what happened. There’s never enough time to share exactly what you’ve been through. Some of the stories that I shared here, I don’t think anyone in my family knows about them,” she continued.

During the event, people like Precious will be able to delve in detail into her experiences. The event gives migrants and refugees space and time to share their stories. There are a lot of misconceptions that the hardest part of the journey is the boat, but in reality, the worst part is getting to Libya.

“That’s where people die, that’s where people give birth, that’s where women are being molested, that’s where people are being robbed, that’s where the worst of the problems are.”

There is no sense of control during the journey and it is detrimental to the lives of millions. An event like this is extremely important because it humanises the reality of seeking refuge in a country like Malta, where thousands come escaping the tragedies they faced on the way.

Tthis event can also educate people thinking of beginning a similar journey, Precious explained. Many tend to underestimate the difficulty and inhumanity that comes with crossing West Africa to Libya, Precious herself did.

“I was similarly foolish because I saw who suffered but managed and I thought to myself, ‘If she managed, I can too.’”

What is often shared in the media is just the surface of the reality and an event like this help showcase the devastating reality of migrating.

“It’s raising awareness for those thinking of starting this journey that it is better to remain at home, hungry than to embark on the journey.”

Such an event will also educate policy makers who may be out of touch with the true hardship people arriving in Malta endure.

“It will let lawmakers know that we’’ve suffered enough. A little bit of peace in our host country will go a long way. Imagine travelling two years to arrive in a country where the suffering continues or can be even worse,” Precious added.

However, the scope of the event will go beyond educating and will also help heal a lot of people who sought refuge. Being able to share stories in an informal, safe space is almost like therapy, Precious said.

“It really does help us.”

If you’re interested in being part of the conversation by hearing the experiences of your neighbours, click here to register for the public event.