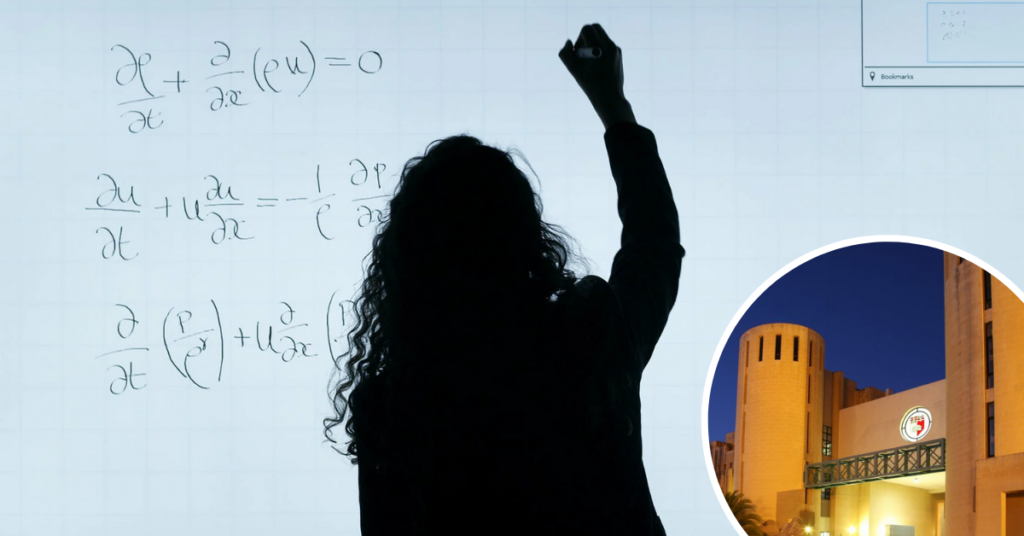

‘I Consider Myself Lucky To Be Single’: The Challenges Female Professors Face At Malta University

This article was originally published on THINK Magazine Issue 35

It’s been over 100 years since the first female student enrolled at the University of Malta. Tessie Camilleri from Sliema entered the university in October 1919 and did an undergraduate course in English and Latin literature, and philosophy.

Today, almost 60% of all students at UM are female. But that doesn’t mean gender gaps are non-existent at the institution; the majority of the university’s top management, deans and directors are male.

Roderick Vassallo, co-chair of the Gender Equality and Sexual Diversity Committee, explains: “You’ll see that there’s quite a number of female academics at the bottom – assistants, lecturers, and senior lecturers. But they start fizzling out at the top.”

The nature of promotions

A lot of it boils down to the way promotions are given. When it comes to professorship, a promotion is given based on conducted research, administration work, and teaching hours.

However, research is given way more importance than the other two. “If you don’t have research published in international journals, you might find that you will not be given a promotion,” Vassallo said.

Josann Cutajar, associate professor in Gender and Sexualities, said: “Women do very well in teaching. But when it comes to assessment, nobody in the university gives promotions on the basis of your teaching acumen.”

Working weekends

On top of that, the current standards set in place are mainly shaped by men. In order to get a promotion, you are expected to work overtime on your weekends – something most men can afford.

But that’s not the case for everyone. Claudia Borg, a lecturer in Artificial Intelligence, said: “I consider myself lucky to be single. It gives me the opportunity to work over the weekend if I want to. I really can’t imagine myself doing the same amount of work if I had a family.”

“But why should a promotion depend on my work on the weekend? Why can’t a promotion be based on working my 40-hour job?”

The bar is set high by those who have the time to work overtime, but it shouldn’t be there for everyone. “Good for them, if they don’t have much to do outside of the university. But the bar should be where we consider it reasonable in terms of output,” Borg continues.

“These are the ways in which university doesn’t support academics. These issues are creating division. There is a gap between those able to do overtime, and those who can’t because they have a life and a family outside their job.”

Why does this impact women?

These things impact women more than men, because in general, it is the woman who has to take care of the kids and the COVID-19 homeschooling. “Some are lucky and have a more balanced load, but parenthood in general more strongly impacts the mother,” Borg said.

Vassallo strongly agrees: “We need to constantly invest energy and mechanisms to help people understand this reality. There needs to be a negotiation between the quality of work and the quality of academics’ life.”

And that isn’t the only way motherhood infringes on women’s production prospects or recruitment. Cutajar said: “If you are female, employers will ask you: what is your fertility plan?”

Vassallo confirms that this doesn’t happen at university as it is in fact illegal, but Borg has experienced it before in other companies. “We’ve had to deal with it time and over again. I have been in a position where I sat for an interview and was specifically asked: ‘Do you have children?’ Or: ‘Why did you get married?'”

The problem is cultural, Vassallo said. “The idea that the family is always dumped on the female counterpart is wrong. Why is the female always in charge?”

Pay gap

Part of the reason women are the ones to stay home with the children is the pay gap. In Malta, men are paid 10% more for the same job as a woman on average. “If my husband is earning more for the same job, I’m going to give up my job because he earns more,” Borg explains.

At university, the gender pay gap exists in indirect ways. “On paper, there isn’t a pay gap. In practice there probably is. Because women will always fall back on not having time to apply for funds and projects,” Borg said.

“The gap comes in at projects where your time is actually paid. The more time you have to work and apply for funding, the more likely you are to receive additional payment for your work.”

Cutajar adds: “There are other things you can be doing, like being the Head of Department or doing research. The majority of Head of Departments and assistant deans are men. So they get an allowance for extra duties.”

Community care

The University of Malta Academic Staff Association (UMASA) has proposed a more holistic approach towards promotions. This would still include a focused approach on research output, but also include the option of taking a balanced approach that gives weight either to an academic’s commitment to university, society, and the academic profession or to demonstrated quality in teaching.

The existing promotions criteria will again be up for review when the next collective agreement is discussed.

Many female academics are involved in community issues. “Research around the world underlines that female academics spend more time with students and advocating for vulnerable social groups,” said Cutajar.

Unfortunately, taking community work into consideration hasn’t been operationalised yet. “That is, we don’t know on which basis you can get a promotion. We haven’t been told what amount of hours equals a promotion,” Cutajar said.

There is also the community within UM to take into account. Helping students is another area that doesn’t currently factor into promotions, but perhaps should.

“We have students with awful problems – suicide, matrimonial issues, abortion… Two of my students had an abortion, so they couldn’t cope. We’ve had a student who got divorced because her husband didn’t allow her to continue her studies,” Cutajar said.

Spending time and effort on helping students infringes on lecturers’ time to do research. Patricia Hill Collins, an American academic specializing in race, class, and gender, once said: “If you want to proceed in academia, don’t do any social help.”

Unfortunately, taking community work into consideration hasn’t been operationalised yet. “That is, we don’t know on which basis you can get a promotion. We haven’t been told what amount of hours equals a promotion,” Cutajar said.

Glass escalator

It doesn’t only depend on the amount of time men and women have to spend on their academic careers. Though there is definitely a glass ceiling in academia, there is also such a thing as a glass escalator, Cutajar explains.

“As a lecturer, your role model is a professor. When you look up and just see men, you think: ‘oh my god, I’m never going to get there.’ We have glass ceilings, but men have glass escalators.”

She elaborates: “Social workers are usually female. When men go into this field, they usually don’t spend as much time at the bottom – they will get to the top really fast. It shows that it takes female academics more time than men to reach their goal.”

Unconscious bias

The issue goes beyond rules and expectations – it is culturally ingrained. “We call it internalised oppression,” Cutajar said. Borg said many parents tell their daughters: “Don’t take computing, that is for boys.”

“I have experienced setbacks, but I can’t always pinpoint whether those setbacks are because I am a woman. The thing is that we have a lot of unconscious biases when it comes to gender,” Borg said.

“In our department, out of 50 lecturers, there are three women. Whenever I enter meetings and I complain, I always find a wall in front of me. There’s an unconscious bias.” And as the criteria for the promotions aren’t strictly defined, it leaves space for that same unconscious bias.

No one will literally say: “There’s a female application, it’s not right to promote her yet. Let’s promote this male applicant.”

“But if you are looking at the female’s CV and you see 10 publications and then you see 50 publications on a male CV straight after, you will likely think she didn’t do enough. Although she may have done a lot of administration, or maybe she has 50 teaching hours.”

Solutions

From the way promotions are granted to the unconscious bias of the men at the top, there are many factors that play into the fact that women are underrepresented in the upper part of academia. Luckily, there are plenty of solutions that can break this glass ceiling.

The three agree that there needs to be more transparency in the way promotions are given, as only the amount of publications is set on paper. Marks should be given for teaching hours and administrative work, too.

Another important step towards gender equality is equal pay and equal maternity and paternity leave.

“Those are the two measures we require,” Vassallo said. “We need the responsibility of the child to be equally distributed between the father and the mother. Then, anyone who will be interviewed who has a child will be liable for the same thing, not just the woman.”

“And more complaints,” Vassallo adds. “When he complains, they listen,” Cutajar said. “When we complain, we are considered hysterical females.” Borg replies: “Of course I am the hysterical female complaining. We’re not going to move forward unless we are shouting.”

What do you think should be done to break Malta’s glass ceiling?