MALTESE HERSTORY: Are You Washing Your Hands To Fight COVID-19? Thank Florence Nightingale For That

Florence Nightingale is a 20th-century icon whose name has a familiar ring to Maltese. But how much do you know about the revolutionary woman? As with all the women in Maltese herstory, the tale of Nightingale is one of broken boundaries, strife and courage. This is the life of an aristocratic-born woman, who gave up wealth, marriage and comfort to heal the masses and also the reason we know to wash our hands to fight diseases.

Nightingale was born in 1820 to a silver-spooned English family, in the Renaissance city of Florence, which she was named after. Her taste for revolutionary thinking was bounded in blood, through their father, a liberal politician.

In an era where a woman’s greatest destiny was to marry and bear children, William Shore Nightingale believed that women possessed similar faculty as men. Florence and her sister Frances benefitted from his progressive ideas, and taught the two history, philosophy, languages and – virtually unheard of for women of her time – mathematics.

Florence stood out as the most academic of her ten siblings – a sponge for knowledge. She was particularly talented at collecting and analysing data, which would serve her well in her life’s path.

As a teenager, her philanthropic affinity emerged at a young age – aiding the ill in a village neighbouring her family’s fabulous estate in Derbyshire. At 17, after a spiritual calling, her mind was set – to be a nurse was her divine calling.

Nursing may sound normal and honourable profession by today’s standards, but it was certainly not the case when the news reached her mother and sister.

A young lady of her class was expected to marry a man of means and tend to his needs, not the needs of the sick. Moreover, the practice of nursing was virtually non-existent in the first half of the 19th century, usually left to former servants or widows with no proper medical or scientific education, and were often described as negligent and incompetent. That is, until Florence transformed nursing upon her return from Crimea.

Florence Nightingale, the world’s first professional nurse

Unfazed by the dismissal of her mother and sister, Nightingale, in her mid-20s, embarked on a self-taught journey to become an expert in sanitation and hospitals. Eventually, her pundit for care was recognised during her time in the Crimean War.

In 1854, Nightingale was asked to nurse British soldiers, deployed to aid Turkey against the interference of Russia. With access to fortune and influential people, she gathered a force of 28 nurses, gave them uniforms and contracts and headed to Scutari, Turkey to the Barrack Hospital. There, their promise of supplies and top-notch facilities was shattered – there was nothing but calamity. A day after the nursing ensemble arrived, the hospital was flooded with wounded soldiers in terrible sanitary conditions.

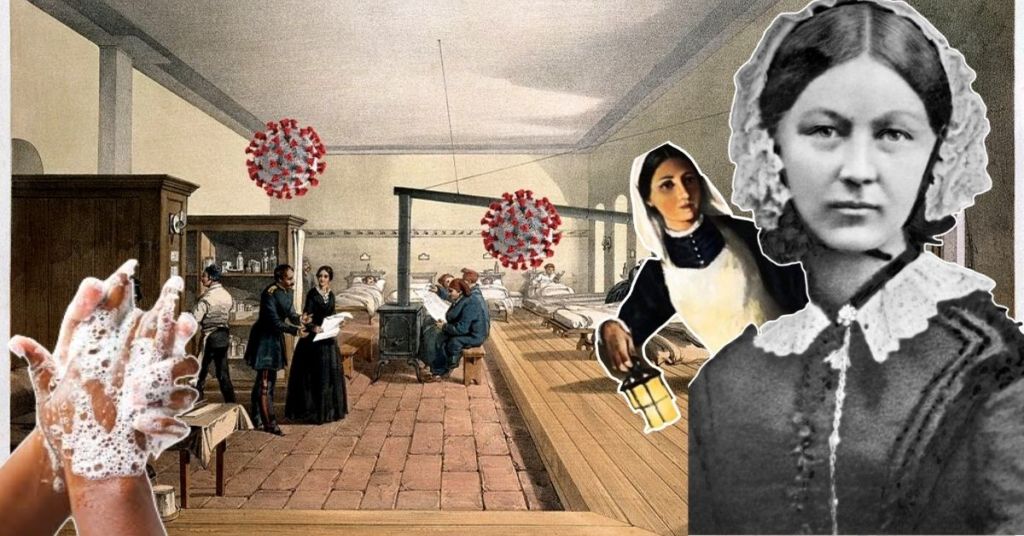

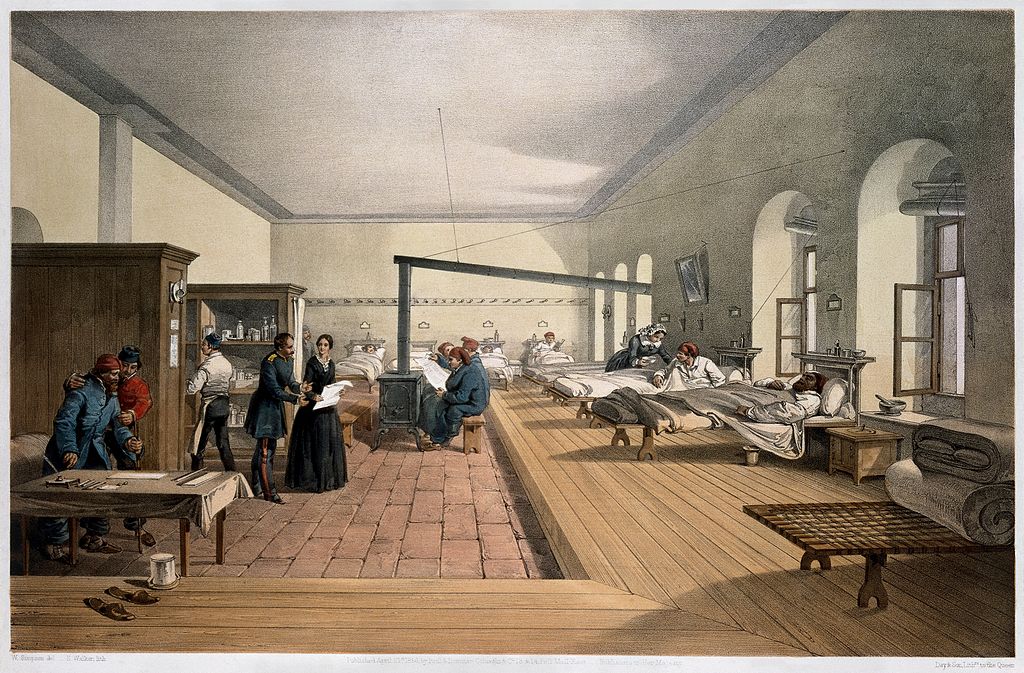

A ward of the hospital at Scutari where Nightingale worked, from an 1856 lithograph by William Simpson

Over 4,000 soldiers died there, however, with overcrowding, overflowing sewers and no ventilation, Nightingale believed that the death rates were due to poor nutrition, lack of supplies, stale air and overworking of the soldiers. In fact, ten times more officers died from illnesses like typhus, typhoid, cholera, and dysentery than from wounds in battle.

Her experiences cemented her advocation for sanitary living conditions in hospitals and in the average household too. She returned to Britain as a wartime heroine, becoming the subject of poems and songs, while her Crimean War reports sparked a revolution for sanitisation in hospital design, the introduction of drainage systems and better hygiene in working-class homes across the world. This stubborn, dedicated woman largely helped increase British life expectancy by 20 years.

Her extraordinary care for soldiers in the Crimean War gained her the nickname of “The Lady with the Lamp” after a news report by The Times:

She is a “ministering angel” without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds.”

Florence Nightingale in Malta

Ward 10 in Cottonera Hospital during World War 1

It’s no exaggeration that Nightingale’s impact was far-reaching, training the first nurse of the United States, healing wounded soldiers, and living conditions of citizens in Britain, India and even the little island of Malta.

Nightingale visited the island on two occasions, first as a tourist in 1849, and then on her way to the Crimea. Malta was a crucial military base. It was where soldiers were trained before being deployed, a depot for ships to replenish in food, repairs and ammunition and as “the hospital of the Mediterranean”.

Her arrival in Malta was highly documented in local newspapers, her short appearance widely celebrated. She even wrote that she wished she had learnt nursing from the Knights of St. John and the way they treated patients with such respect and dignity.

Her visit also inspired a part of one of her fundamental writings that would interest any medical student in Malta today. Her work entitled “Notes on Hospitals”, includes detailed plans to “place this small island in the foremost rank as regards its charitable institutions”.

It proposed the General Military Hospital in Valletta, the Asylum for the Aged and Infirm and Hospital for Incurables, all with pioneering sanitary designs which would prove effective after her time in Crimea.

In line with proposals drawn up by Nightingale, Malta’s Cottonera Hospital was built in 1873, one of the first major hospitals to have groundbreaking sanitary practices inbuilt into its design. It was well-ventilated, had running water, a separate ward for contagious diseases, and each bed was given 1,500 cubic feet. It’s no wonder the state-of-the-art hospital was dubbed the best in Southern Europe and went on to be a fundamental pawn in World War 1.

Nightingale, writer, reformer, revolutionary woman

There are countless fascinating facts surrounding Nightingale, her character, work and legacy. She was widely described as beautiful, carried herself gracefully with a charming and radiant smile – but her stubborn drive to fulfil her life’s calling is her attribute we should thank and take notes from. She turned down two marriage proposals, the easy life of an upper-class woman to make strides in history.

Florence Nightingale, who never married or bore children, would never live to see how her designs helped Malta heal thousands of soldiers wounded in The Great War. She fell ill in 1910 with severe case of Brucellosis, also known as “Malta fever” and died.

Known for her contributions to nursing and also mathematics, with countless schools, medals and funds bearing her name, Nightingale also played an important part in English feminism. She wrote some 200 works books, pamphlets and articles in her life, including “Cassandra”, a protest to the over-feminisation of women into impotence, her spiritual ponderings and of course, medical analysis.

Florence Nightingale posing with her class of nurses from St. Thomas' Hospital, set up in 1860.

International Nurses Day is also celebrated on her birthday, while nurses across the world take the Nightingale Pledge at the end of their training. It honours Florence Nightingale as a pledge of ethics and principles embodied by the founder of modern nursing.

In Malta, the Florence Nightingale Benevolent fund within the Malta Union of Midwives and Nurses organises a presentation ceremony, to celebrate and give thanks to its members who have retired from their nursing career.

Nightingale’s mark on history holds particular significance today, as the world continues to battle the COVID-19 virus. Whenever you wash your hands, remember Florence Nightingale’s defiance, the lady with the lamp, a baton now carried by nurses and doctors on the frontlines of this pandemic.

Tag someone who needs to know about Florence Nightingale