MALTESE HERSTORY: Malta’s First ‘She-Chemist’ Was A Rich, Promiscuous Slave Owner

Caterina Vitale bore many hats to her contemporaries in the 16th century, a high-class whore, a firm businesswoman, a sadist and supposed witch… and Malta’s first recorded pharmacist.

Known as ‘La Speziala’ or the she-chemist, Caterina Vitale was born to Greek parents, in 1566 just as Valletta was being built. Barely a teenager, she was married off to a Neopolitan man called Ettore Vitale, the chief pharmacist to the Knights of St. John.

When Caterina was 27, Ettore died and she took over the pharmacy, supplying crucial medicine to La Sacria Infermeria; the flagship hospital was known as the ‘Holy Infirmary’ off the Grand Harbour.

Depiction of a French chemist in the 15th Century

Some say her husband was killed by a bomb, but law historian Giovanni Bonello claims the bomb exploded outside one of the widow’s houses on Archbishop Street in 1593.

In fact, three commissioners were appointed to investigate the attempted assassination of Vitale, who was rumoured to be a wealthy witch and a whore, floating between Knights of the Order and blackmailing them.

As Susanna Hoe writes in her enlightening book Malta – Women, History, Books and Places: “Perhaps what is more likely is that she was rather litigious where Knights were concerned, to do with money and business rather than sex.”

Courtesy of Vassallo History

It is not unlikely that her power as an independent woman in the 16th century, quite unheard of at the time, would bring about such attempts to tarnish her name.

Indeed, claims of witchcraft and promiscuity were never proven, but there is little doubt of her knack as a vigorous businesswoman.

“She and Ettore engaged in buying and selling property and socks of medicine and, like many of her contemporaries, Caterina made ‘good money’ by dealing in slaves,” Hoe wrote.

However, her treatment of black and Muslim slaves and her behaviour towards her adopted child Isabella, paints a darker portrait of the she-chemist.

Three of her slaves took Vitale to the Inquisitor’s court at least three times, accusing her of sadistic torture, witchcraft and perpetrating carnal sexual abuse together with some of her friends in armour.

Tribunal room at the Inquisitor's Palace

Like many people with friends in high places, the crafty she-chemist escaped major punishment but was ordered under house arrest for an unknown amount of time.

Although it is not known how long Isabella lived with her mother, she eventually ran away to join the Maddalena, which, as historian Christine Muscat says, was a convent for fallen girls or prostitutes who wished to turn away from the trade could go.

Vitale had other plans in mind and visited the nunnery to exhort her on several occasions, once declaring she wanted to see it in ruins and was temporarily banned from visiting. She would be vindictive towards Isabelle in her will, leaving her with a pittance.

Vitale led a colourful life to say the least, refusing to submit to the “intolerable and unrealistic” precepts laid down for widows by the Catholic Church.

Pietro Bertelli’s flip-up courtesan shows off the woman’s chopines as well as her undergarments. (c. 1588)

As Carmel Cassar explained: “It may be because she was Greek and had more sympathies with Greek Orthodoxy and Greek culture”.

Archbishop street, where she had two houses, was known as Strada del Popolo under the Knights, but also known as Strada Dei Greci, perhaps not connected to Caterina but the fact that the Greek Orthodox Church, Our Lady of Damascus, was under construction.

She died in Syracuse, aged 53, and would be known as a generous philanthropist for the project she embraced later on in life.

Vitale donated her property, jewellery and money to various people and opened various foundations; like one for her own soul in the monastery of St. John the Evangelist, on one of the Dodecanese Greek islands.

In 1583, she set up a foundation in the Carmelite church, dedicated to the soul of her mother, herself and her descendants, where she would later be buried with her husband and parents.

Basilica of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Valletta

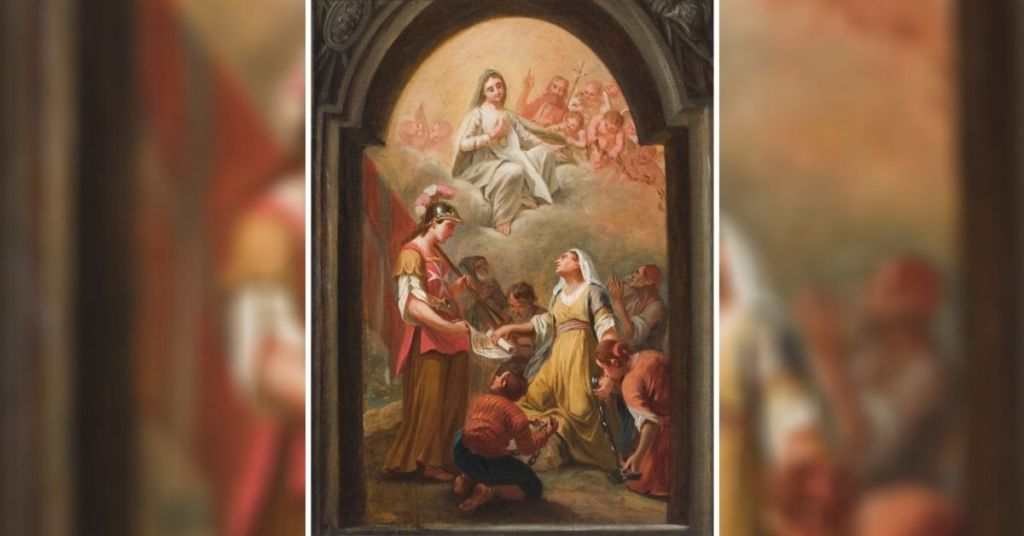

Because of her hefty donations, portraits like this by Antoine Fairy commemorate her. Bonello’s tongue-in-cheek description is perfect.

“A lovely, but imaginary portrait of her, painted in 1760 by Antoine Favry for the main altar of the church of Selmun, shows her press discussing the pros and cons of chastity with the Virgin Mary, who seems to have already made up her mind.”

As Susanna Hoe perfectly sums up: “In one woman, indeed, is contained many of the possibilities for a man of the sixteenth and seventeenth century.”

Tag someone who needs to learn about Vitale!