Wait Until The Bus Stops: An In Depth Look At David Schembri’s New Photobook On Malta’s Old Buses

Malta’s vintage orange buses have long faded into a nostalgic memory for many, reminiscent of a part of the islands’ history that has long ceased to exist.

When I found out David Schembri has just published a book, his first, featuring photographs all taken in the last month before the old Maltese buses were replaced, I was immediately intrigued to revisit this distant part of my memory.

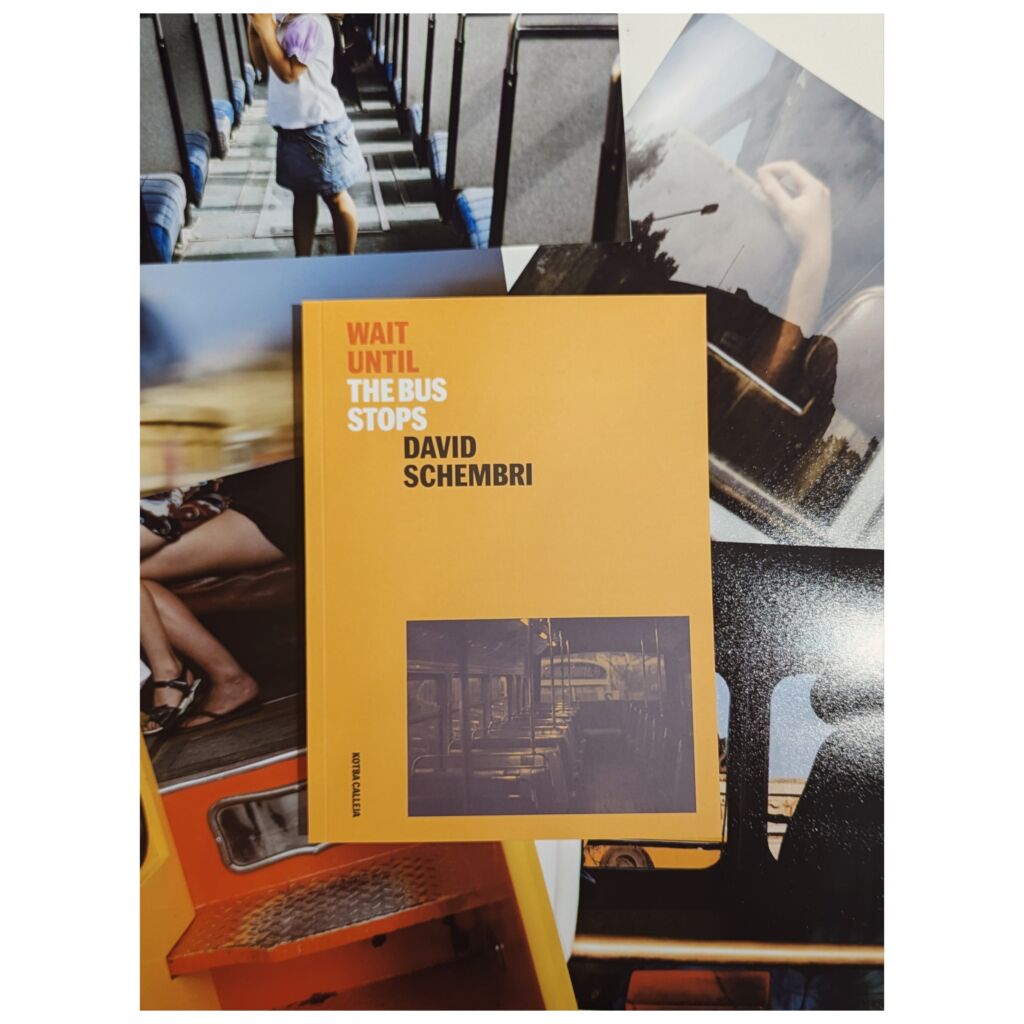

The book, Wait Until The Bus Stops, was edited and published by Glen Calleja, from Kotba Calleja – and it is currently available for sale at their stand at Malta’s ongoing National Book Festival.

I sat down with David Schembri to have an in depth look at his newly published book, and to find out more about the inspirations that drew this into reality.

What inspired you to start photographing Malta’s buses in June 2011?

At the time, I worked as a journalist in the Times of Malta’s newsroom, and one of the topics I covered was the public transform reform, which would see the old Maltese buses being replaced with the Arriva fleet.

I realised that a unique part of our country’s landscape and collective imagination was going to be lost certainly in the way we knew it, and I set out to capture as much as I could of what fascinated me about these buses.

So you could say it was a mixture of love and fear that drove me to spend all of that month obsessively taking photos of buses. And the fact that it was their last month on the roads, albeit quite poetic as an idea, is also because I’m a bit of a procrastinator. I’m actually quite impressed at my past self that I managed to capture a month, rather than the last day!

Were there any memorable encounters or specific bus journeys that stood out to you during your month of photographing?

I’m from Nigret, on the outskirts of Żurrieq, and when I was a teenager I was often the last passenger on the bus. I’m not sure how it is today, but it was very common back then for drivers to work the same routes, so eventually you become familiar, and eventually you end up chatting with them and getting to know them a bit.

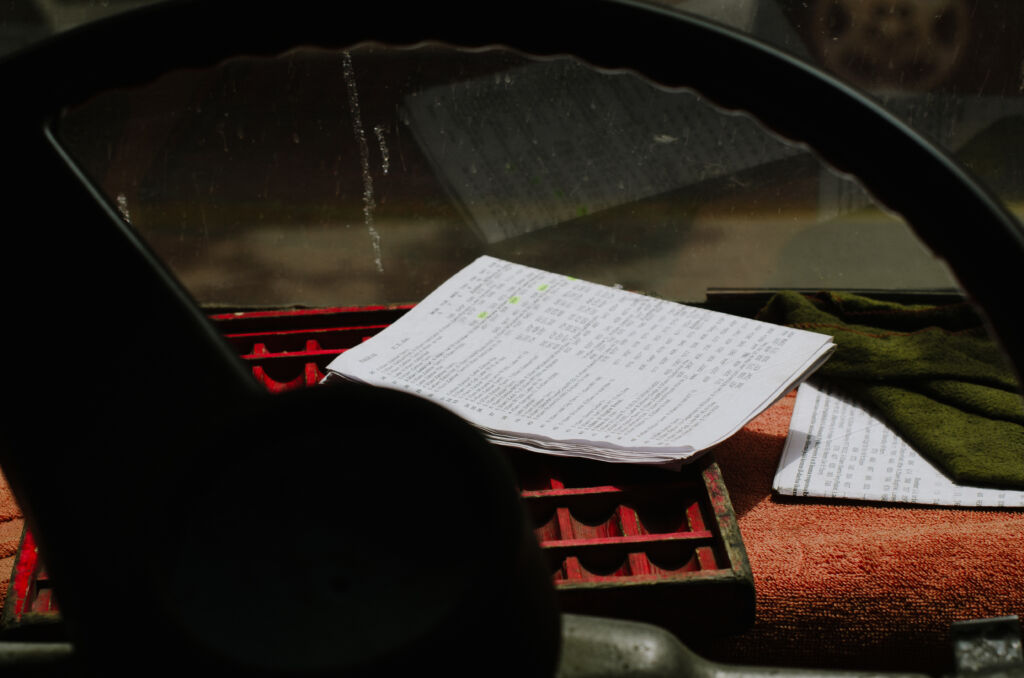

Shooting this project was a bit like that – getting to know the drivers, not only through speaking to them, but also through their bus, which many times they owned themselves, and would have customised and modified over the years. One memory I cherish is also tied to one of my favourite images in the book, that of a driver’s young daughter running around the bus with such familiarity, as if it were her home. These buses weren’t just vehicles, they were something more.

How did you go about selecting the images for this book from the thousands you took, and what story do these chosen photographs aim to tell?

The selection process was shared between Glen Calleja, the editor and publisher, and myself. Back when I was pitching the book to publishers, I had put together a portfolio of what I felt were the strongest shots that gave the work the best shot possible. Glen, from his part, asked me to give him all the photos (over 5,000 in total), and he made his own edit, which includes photos from my shortlist and his.

When I set out to photograph the buses, I started out by zooming into the little details which fascinated me, a kind of deconstruction in which you abstract little details – such as the textures of the fabric on the seats, a patch of rust over tberfil, the handwritten signage – but eventually I became more interested in the way people related to them.

The project includes a mix of both, but I think it’s more biased towards the latter, perhaps more photojournalistic style of photography.

Can you describe the experience / emotions of revisiting these photos over a decade later?

The project was always on the back of my mind, but in some cases I would look at a photo which turned out particularly well and surprise myself because it wasn’t something I remember taking.

Some four years ago, the hard disk on which I kept my photos failed catastrophically, and I ended up losing around six years’ worth of photos. Luckily, the bus photos were also on another drive, and that gave me the motivation to get these out into the world.

Looking back at them, I’m glad I managed to capture what I treasured about these buses, because the way I feel about them now is the same way I felt back then.

What role did your collaborators play, like Glen Calleja with the editing and Marco Scerri with the design, in shaping the final look and narrative of Wait Until the Bus Stops?

Glen, of Kotba Calleja, is at ease in the literary and the visual world, and cares deeply about the content of a book as well as its form – I think he’s the only person I know who writes, edits, and binds books himself. Since this project is so concerned with materiality, it was vital to work with someone who cares about the book as an object in itself.

He was instrumental in choosing what to include and to leave out, and the final product is a result of his vision. He also invited me to write short texts, which range from the reflective to the personal, mostly around the theme of movement.

Marco Scerri is one of my favourite designers and I was thrilled he agreed to work on this project. He is a lifelong student of design, typography and photography and his design helped give the book’s contents rhythm and room to breathe. His cover design – with typography echoing that of the route numbers and the colours echoing the main colours you’d see on the buses – manages to pay homage to the subject matter without being obvious.

In what ways do you hope this book resonates with Maltese readers or anyone interested in Malta’s history?

If it resonates in any way with readers, it’s enough. It would be nice if it reminded people to not take whatever makes up our heritage for granted and to work to keep it alive, before it’s too late.

If you’re heading to the Malta National Book Festival this weekend, be sure to give this one a look