Data Protection Commissioner Distances His Office From Courts’ Removal Of Judgments From Online Database

Malta’s Data Protection Commissioner has distanced his office from the Court Services Agency’s removal of judgments from its online database, despite the Justice Ministry’s claims that the system for doing so has the office of the commissioner’s blessing.

According to a reply by Justice Minister Edward Zammit Lewis to a parliamentary question last week, 295 people have had their judgments removed from the courts’ online database on the basis of the ‘right to be forgotten’ since 2017.

The ‘right to be forgotten’ principle is outlined in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which specifies that people have a right to request the deletion of personal data held by an entity removed if they have not consented to it, or if it is no longer necessary for the entity to keep it.

The regulations however clearly state that this right does not apply to instances where the processing of that data is required by the laws of a country or is essential to the public entity carrying out its role.

Various legal experts, including former European Court of Human Rights Judge Vanni Bonello have pointed out to Lovin Malta that the Constitution itself – the supreme law of the land – requires court proceedings, and their judgments, to be made public in the interest of transparency.

Asked about this fact, as well as the criteria used to determine whether or not a judgment should be removed from the online database, the ministry simply insisted that the “process of removing judgments from the Court Services Agency (CSA) online system is in line with GDPR regulations, and the principle of transparency”.

“The judgments remain available to all those who have an interest, as well as legal professionals. Judgments are only removed after consultations and discussions are undertaken from time to time, between the Internal Court Services Agency Administrative Board, the Office of the Information and Data Protection Commissioner. Established criteria that are used (mentioned in the PQ) were developed on the basis of the GDPR and consultation with the Data Protection Commissioner that the criteria were set up,” a ministry spokesperson told Lovin Malta.

Justice Minister Edward Zammit Lewis

Lovin Malta also asked the Office of the Information and Data Protection Commissioner for its position on the matter, as well as about assertions by the ministry that the IDPC is consulted from time to time about such requests.

“Our office is not a member of, and has no direct or indirect involvement in, the ad-hoc committee which decides on these cases. We are not consulted on the determination of these applications. Any similar involvement would certainly be prejudicial to our regulatory duties,” Data Protection Commissioner Ian Deguara told Lovin Malta.

As for whether it had been consulted on the criteria used to determine whether or not to accept such requests, Deguara said the IDPC was never consulted.

“A couple of years back we were involved in discussions with the CSA, specifically on the matter of general data protection principles which are applicable to these kinds of requests made by data subjects for the removal of their personal data from the online system.

“Apart from that, I am not informed that we have provided any form of feedback to the controller (the CSA in this case) during their process to determine whether a judgment should be kept online or removed from the system altogether,” Deguara said.

In comments to Lovin Malta last week, privacy lawyer Antonio Ghio pointed out the need for the criteria on the basis of which judgments are removed to be enshrined into law in order to ensure greater transparency, a suggestion Deguara said he supported.

“Concerning the guidelines used by the ad-hoc committee in their deliberations on requests for removal of judgments, in the spirit of ensuring legal clarity and certainty, I am in favour of giving these criteria a legal standing,” Deguara said.

He would not be drawn into whether or not the removal of judgments went against the spirit of the regulations being cited, or whether the criteria being used were in fact enough, telling Lovin Malta that this was ultimately the responsibility of the courts.

“This is more a matter relating to the application, in practice, of the right of erasure by the controller, which must be seen in the light of the exemptions set out under Article 17(3) of the GDPR and the relevant CJEU jurisprudence on the subject matter,” Deguara said.

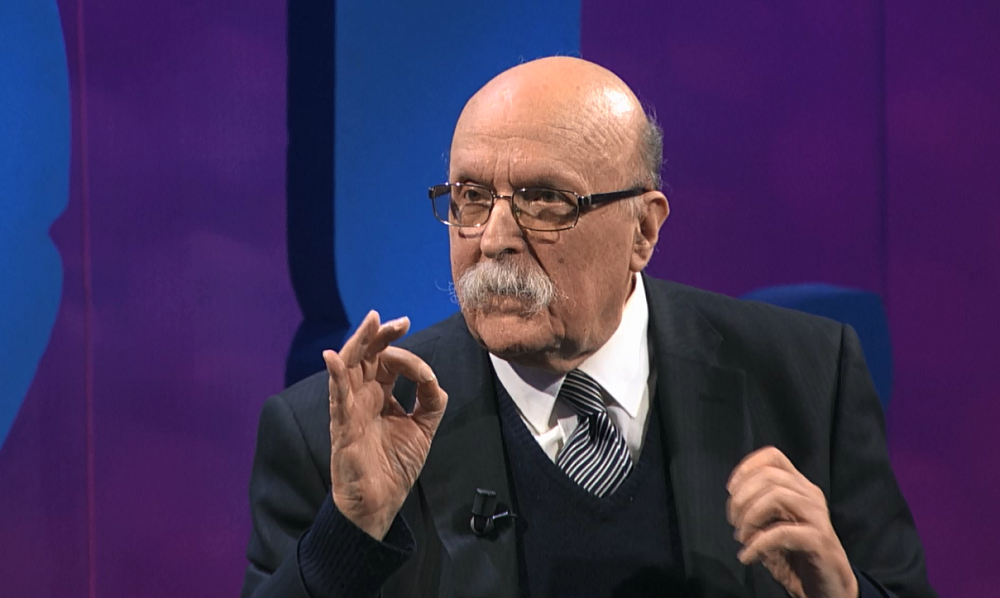

Former ECHR Judge Vanni Bonello has noted that the Constitution requires court judgements to be made public

So what does the GDPR say anyway?

The Article of the GDPR cited by Deguara relates to specific scenarios where the right to be forgotten does not apply, which includes situations where the personal data is being processed “for compliance with a legal obligation which requires processing [by Maltese law] or for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or the exercise of official authority”.

In this case, making public the outcome of court proceedings is required by the Maltese Constitution. It is also a requirement under Article 6 of the European Charter on Human Rights.

The European Court of Human Rights has in fact pronounced itself on this on a number of occasions on the matter, noting that the “complete concealment from the public of the entirety of a judicial decision cannot be justified”.

It must be said that in this case, at least according to what we’ve been told, judgments have not been removed from the actual register and anyone who physically goes to court and requests to see the case file can do so. It nonetheless feels like the policy goes against the spirit of the reguations.

According to the minister’s parliamentary question reply, judgments removed from the online database are removed on the basis of preambles 65, 66 and 156 of the GDPR as well as Article 17 of the same regulation.

A reading of the regulations, however, shows that none of the provisions cited justify the removal of court judgments. Preamble 65 actually expressly states that data need not be removed in cases such as this. Preambles 66 and 156 on the other hand aren’t really relevant to this discussion.

It is difficult to imagine a circumstance in which the removal of a court judgment could be justified.

This is especially true when considering that in most cases, especially with more recent judgments, a Google search for a particular person’s name won’t bring up a link to the Court Registry website. More often than not, it is people searching for a judgment who will find it.

But even if one were to accept that there could be legitimate reasons for removal, one would expect this to be done in as transparent a manner as possible, and on the basis of clear, transparent and legally binding criteria.

What do you make of this story?