Guest Post: Al-Arroub, A Photo Story Of Lives In A Palestinian Refugee Camp Under Israeli Occupation

While studying in Jordan in September 2023, I crossed the border to the Occupied West Bank and spent two weeks in Al-Arroub Refugee Camp, which falls under area C, meaning it’s directly under Israeli Occupation. I met many Palestinian refugees while there, who told me their stories. I could also observe the dire state of the refugee camp under Israeli occupation and how Palestinians resist in their day-to-day lives.

In this photo article, I aim to showcase what I could observe and learn in Al-Arroub refugee camp through my photography, as well as the stories I’ve been able to gather.

Panoramic views Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Panoramic views Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Panoramic views Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

1. When I went

When you hear ‘refugee camp’, what do you think of? Big tents set across an open space? What happens when a space and a people have remained in a state of impermanence and insecurity for over 75 years? How does a refugee camp transform in the span of generations? How do people who are born and die as refugees live? How do they build a functioning society despite the obstacles that they face?

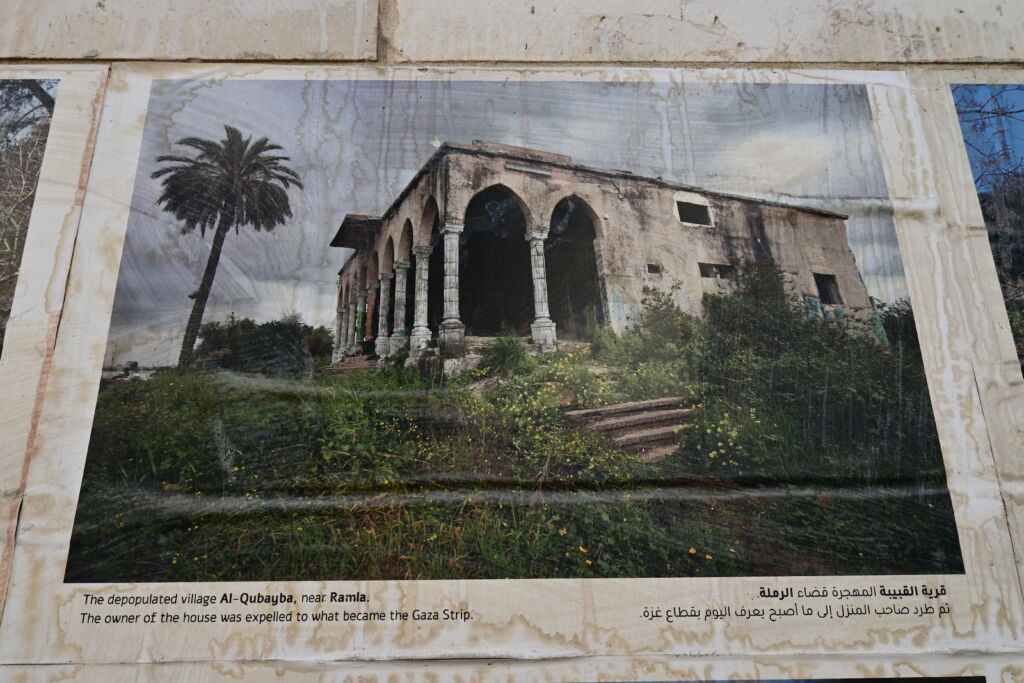

These are questions I like to pose when talking about Palestinian refugee camps, many of which have existed for over 75 years. A refugee camp is usually understood as a temporary measure, however, that has not been the case for Palestinian refugee camps, to the point where generations of Palestinian families have grown in them. These camps have transformed into villages, but the status of their inhabitants remains that of refugees. The existence of these refugee camps is linked with the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians by Israel since 1948 and is a lasting reminder of the losses and state of impermanence generations of Palestinians have had to endure.

The dire state of the refugee camp

The dire state of the refugee camp

The dire state of the refugee camp

The dire state of the refugee camp

The dire state of the refugee camp

Al-Arroub is a Palestinian refugee camp, located between the cities of Bethlehem and Al-Khalil and is inhabited by over 15,000 people. It falls under area C, which means it’s controlled by Israel. When I arrived there I was shocked to see a village. One can observe its poor conditions. It is small and compact, with very narrow alleys separating each building, and large families living in small spaces.

Yousef explained that access to water was not always adequate and that since 1982, they started receiving water from Israel instead of UNRWA. They would supply them with water only twice a week. Since the first Intifada, the Israeli forces started cutting their water supply regularly as a form of collective punishment. They didn’t have any electricity till 1989. The camp itself is surrounded by Israeli checkpoints, including a control tower with automated rifles on the front façade at the entrance of the refugee camp where Palestinians in Al-Arroub catch the bus every day.

Control Tower in Al-Arroub

Control Tower in Al-Arroub

Control Tower in Al-Arroub

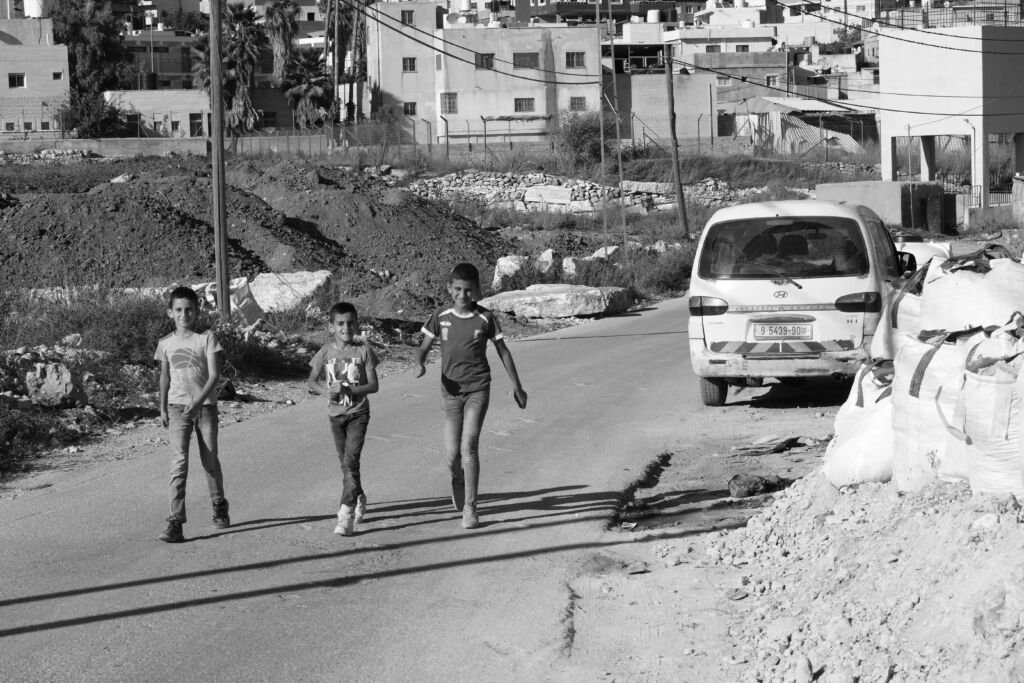

During my stay in Al-Arroub I could observe the dire state of the camp, the Israeli control tower, the bullet holes, and the suffering. With that said, this did not deter the Palestinians’ thirst for life. Despite the constant threats imposed by the occupation, I could see their comradery and their resilience. I watched refugees open restaurants, children play in the street, and men catch up with each other at the barbershop.

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

People of Al-Arroub

I wrote extensively on my experience in Al-Arroub refugee camp in A photo story: contrast of lives in the West Bank that I published for The Perspective UPF Lund.

2. A family’s life in Al-Arroub: a story of struggle spanning three generations

My friend Yousef’s family is originally from the village of Agour, which now falls under Israel, following the natives’ forced displacement in the Nakba. Now, from what I’ve been informed, it’s a primarily abandoned kibbutz used for agriculture.

We talked extensively about his father, who was 19 years old when the war started in 1948 and held a British passport since he lived during the British occupation. Until 1995 his ID showed that his birthplace was Agour. Upon renewing it, they eliminated the name of the village and wrote Israel, as a way to erase his Palestinian heritage. From 1948 till 1951 his family was living in a tent in Al-Arroub. Everyone depended on UNRWA for food and water. Before the Nakba, he was a shepherd, but his life changed since the start of occupation and had to become a construction worker. His way of life was completely taken from him. Despite not having a high level of education, he was the only breadwinner in the family, which included eight children as well as his parents.

In his last years, his father used to break into tears every time he remembered his life in the village of Agour before Nakba. He didn’t want to let go of his past life, which he loved so much and that was abruptly taken away from him by Israeli settlers. He died wanting to return to that life. He used to ask his family “When can we go back to our village?” He was always sitting at home in silence reminiscing about his life in Palestine before the partition and subsequent occupation.

Yousef’s father was separated from his brother in the 1967 Naksa, which saw Israel occupying Gaza, the West Bank, and parts of Egypt and Syria, which, in the case of Syria’s Golan Heights region, is still occupied until this very day. His brother was living in a Palestinian refugee camp in Jordan at the time. He didn’t see him until 27 years after Naksa, since the border between Jordan and the West Bank was completely closed, following the Israeli Occupation of the West Bank.

A Palestinian Refugee Camp in Jordan

The occupied Syrian Golan Heights seen from Jordan

His mother, also from Agour, suffered as much as his father. She was 13 years old when her family was forcefully displaced from Agour. Her life in the refugee camp was as hard. She had to go down the hillside of the refugee camp to the entrance to get water from UNRWA (when it was still supplying the refugee camp with water) and then carry it uphill herself.

At the time, UNRWA supplied each household in Al-Arroub with a gallon (3,8 litres) of water a day. She also had to wash the clothes at the outskirts of the refugee camp and had to leave the village every day to get wood to use for daily necessities like cooking. Yousef’s mother had to do all of this while taking care of the eight children.

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

For Yousef, life has been quite hard. UNRWA provides education till they reach 15 years of age. In his time, every classroom had 50 students. For post-secondary (16 to 19 years of age) he had to walk 3.5km to the school and 3.5km back everyday, since there was no transport. To add insult to injury, when Yousef was in post-secondary, the Gulf War involving Iraq occurred.

Everything was halted during this time since Iraq was launching missiles towards Israel. He couldn’t attend school for around two months. Later on he got a scholarship to study at the University of Bethlehem. He said Palestinians and especially Palestinian refugees like him are motivated to continue their education since it’s the only thing they have.

A school in Al-Arroub

He always emphasises how the situation is tiring and hopeless. He doesn’t have the freedom to go where he wants and it’s impossible to organise his life or have any future plans. The situation is constantly changing and the Israeli forces impose new restrictions every other day (since the beginning of the occupation decades ago). He told me “I know we are used to this type of life but it’s not life. What kind of life is this?”

Yousef’s family’s younger generation has also been traumatised, with several of the younger family members targeted by the Israeli forces. Two of his nephews are currently in prison, while another one of his nephews was released two years ago since he was the youngest and injured by Israeli soldiers, who shot him with four bullets in his leg.

When he was discharged from the hospital, the Israeli forces went to his family’s house (my friend’s older brother) and detained him again for four months. They were able to bail him out by paying 8,000 shekel (equivalent to around €1,960 which is a lot of money for the family). He was only 14 years old and unarmed when this happened.

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Al-Arroub Refugee Camp

Last July, the Israeli forces detained another of his brother’s sons, who was 19 years old. They imprisoned him for 36 months. After 7th October, they also took another nephew, also 19 years old, who was studying to become a nurse. The Israeli forces broke into his family home in the middle of the night, shouting and breaking the main door. They forced all the family members (including little girls) to go to a room while they searched the house and threw everything to the ground. The little girls were terrified since the soldiers had their cheeks painted and brought two big German shepherds with them to scare off the family.

They started hitting Yousef’s nephew in front of all the family and then took him to a prison. The family still has no idea which prison they took him to or what they’ve done to him. They have not been given any information by the Israeli authorities. His younger brother and sisters are traumatised until this very day. The trial in the military court (Palestinians, including the underaged, are all subjected to military court by Israel, unlike Israelis who are subjected to civil court) has been postponed four times. He’s already been imprisoned for six months and no one knows for how long he’ll be there. The judge recommended a sentence of three years and a half in prison, however, the ruling hasn’t been made yet, due to it being constantly postponed. The Israeli forces took him without any reason, as they do in most cases.

Yousef’s nephews are a few of the thousands of Palestinians detained and imprisoned by the Israeli forces with no justification. They are held as hostages by the State of Israel and their future is uncertain.

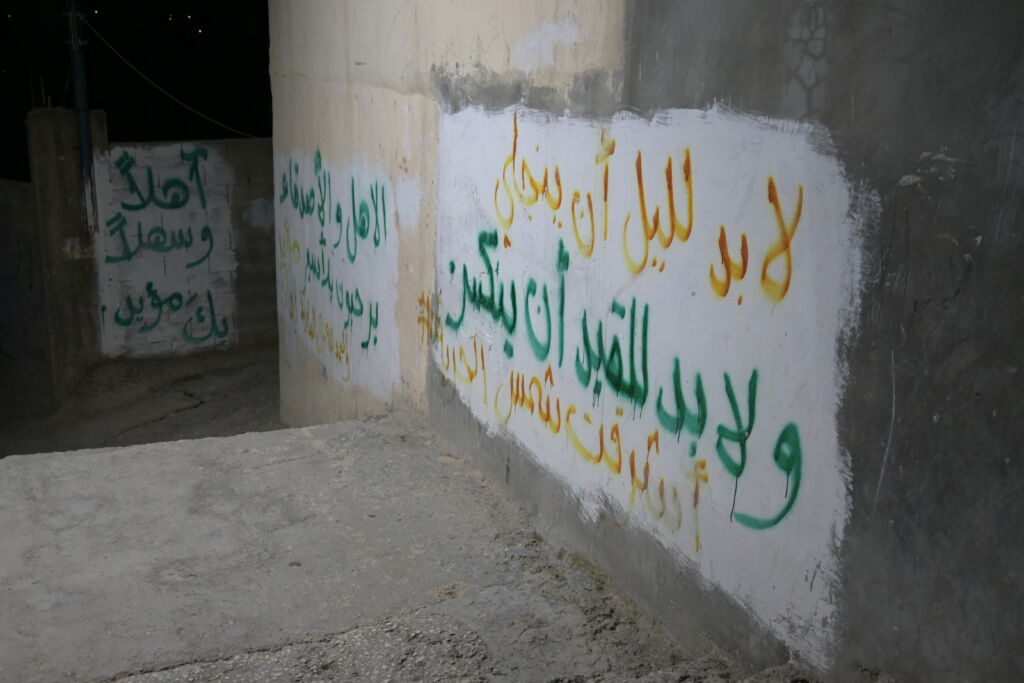

A Poem on a wall in Al-Arroub of someone who had been to prison

3. Al-Hajj

Al-Hajj

This man, known as Al-Hajj, is 77 years old. He was born before the Nakba (1948) in the village of Agour (like Yousef’s family). He has been a refugee since he was two years old, when his family ended up in Al-Arroub following their forced displacement by Israel.

Al-Hajj suffers from many illnesses, but the medication is too expensive. His children are unable to buy it as a consequence of the ongoing war. He depends on other refugees’ generosity. He used to receive 60 shekels (around €15) worth of aid from UNRWA every three months. Now I’ve been informed he’s only receiving 40 shekels (around €10) every three months. He only gets the basic medication from the UNRWA pharmacy since it doesn’t have all the required medication. He is supposed to buy the rest himself with the equivalent of €10 every three months.

He lives alone with his wife. During Ramadan, some people in the refugee camp provided him with some food to eat. He’s always in his room and does not go out. He suffers from depression and is constantly thinking about when he’ll die. To add insult to injury, all of his siblings have passed away and he’s the only one left. He’s really thin due to the stress of always thinking about the hardships of his life. This is the life of most elderly people in Palestine.

Most refugees across the globe hold their citizenship regardless of their refugee status. However, Palestinian refugees have no citizenship. They are refugees in their own land, which makes them eternal refugees and citizens of nowhere, like Al-Hajj and Yousef’s family.

4. Martyrs: Children and youth killed in Al-Arroub

In 2023, the Israeli forces killed five youths in Al-Arroub. Before I arrived in Al-Arroub they had killed three children (one a week before I arrived) and since 7th October they’ve killed two more. One was killed very close to Yousef’s house, while he was walking with a friend between the village of Bayt Fajjar (which falls under area A – Palestinian Authority control) and Al-Arroub. He had problems with sight.

Israeli soldiers were passing by in a car and asked him and his friend to stop. They both stopped, but this didn’t deter the soldiers from shooting him in the head. The soldiers’ excuse was that they were not stopping…from walking. As if that were a justifiable reason for killing him. He was 19 years old. His family has been devastated ever since.

When I was in Al-Arroub I could see images of martyred (Palestinians killed by Israelis are described as martyrs) Palestinians all over the camp.

Martyrs of Al-Arroub

Martyrs of Al-Arroub

Martyrs of Al-Arroub

Martyrs of Al-Arroub

A week before I arrived, there were clashes with the soldiers at the entrance of the refugee camp. The Palestinians of Al-Arroub were protesting against Israel’s operation in Jenin Refugee Camp (Northern West Bank). Even before 7th October, the Israeli forces invaded the Jenin refugee camp. Around three to nine Palestinians in that refugee camp were being killed every day.

Israeli forces’ raids and break-ins have also increased in Al-Arroub since 7th October, however, even when I was there, I could see evidence of struggle and bullet holes in the campsite, especially the closer it got to the Control Tower.

One of the youths I spent time with even told me how he narrowly dodged a bullet shot by an Israeli soldier just a few weeks before.

Evidence of struggles in Al-Arroub

Evidence of struggles in Al-Arroub

Evidence of struggles in Al-Arroub

Israel’s decades-long occupation of Palestine has left a trail of destruction and apartheid. I hope that through these photographs and stories you can see the humans behind the numbers and statistics.

Everyone wants to live their life in dignity. Palestinians have been treated like lesser human beings by a settler group that decided to build a nation on their land, without their consent.

Just ask yourself, what would you do if you, your family and your nation were placed in that situation for nearly a century. How would you react? Do you deserve to live through it? I imagine your answer would be no, so then I ask, why should Palestinians be put through this? Why should people live and die as refugees in their own land?

I’ll leave you with this picture of a group of shabab (youth) posing for a photo in Al-Arroub Refugee Camp. They all have hopes and dreams for their future, just like you and I. So why shouldn’t they have the same rights we have been given?