State An Accomplice In Omerta’ By Applying Right To Be Forgotten To Court Judgments, Former Human Rights Judge Says

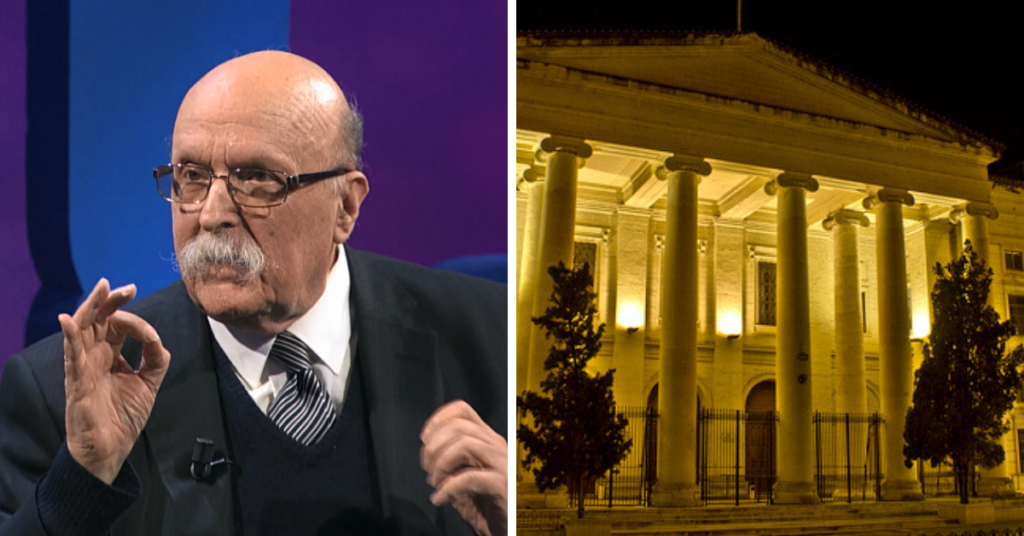

The removal of sentences from the courts’ database on the basis of the right to be forgotten is resulting in the state becoming an accomplice in omerta’, through its censoring the public findings of the criminal court, according to former European Court of Human Rights judge Giovanni Bonello.

Earlier this week, Justice Minister Edward Zammit Lewis provided statistics on the number of individuals who have had applications to have their sentences removed from the courts’ database accepted, in response to a Parliamentary Question by Opposition MP Joe Ellis.

According to the statistics, 295 sentences have been removed from the database since 2017, the majority of which being sentences handed down by the Criminal Court.

The minister also provided parliament with a brief description of how a decision on such applications is taken, telling the House that applications by people who have been found innocent by the courts are automatically removed.

The courts have removed 295 sentences from their online database since 2017

“It is the Constitution itself that demands publicity in all criminal proceedings,” Bonello told Lovin Malta.

“Publicity serves a double purpose: it favours the accused by ensuring that the actions of the state are all subject to his or her scrutiny, and it favours the community in so far as it ensures that justice is administered in a transparent manner.”

The principle of publicity in criminal matters, Bonello argued, was basic to good governance and the proper administration of justice. “Publicity is the rule, secrecy is the very limited exception.”

Bonello said that the right to be forgotten had been “entirely deformed in Malta”, arguing that it was intended to protect the right of privacy abused by for-profit commercial enterprises, like Google and other social media companies.

This, he said, was justified because “personal data should not be consumables for commercial profit”.

“Wholly uncritically, the limitations placed on commercial enterprises not to publicise sensitive ‘criminal’ information about individuals have in Malta, been corrupted into a duty placed on the state to shield criminals from the consequences of their actions. It has, in Malta, become a system by which the state becomes an accomplice in omerta’, in censoring the public findings of the criminal courts,” he said.

Guidelines for removal of sentences need to be enshrined in law

Antonio Ghio, a lecturer in data protection law at the university, pointed out that one could not simply invoke general rights laid out in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), without having proper guidelines, outlined in subsidiary legislation, about how the right is being implemented.

He said that while one could envisage a scenario where some data is removed on the basis of the right to be forgotten, this needed to be done in a transparent manner.

“There isn’t sufficient proportionality and transparency in the way things are being done. The rules, as they have been presented, aren’t good enough,” Ghio said.

“The underlying application of the right to be forgotten to court judgments is still very vague.”

While the minister said that the decisions are taken by an ad hoc committee consisting of government appointees, Ghio insisted that this wasn’t enough.

For the right to be applied and for public interest considerations to be evaluated properly there needed to be more than just guidelines, but legal provisions.

“How is the ad hoc committee deciding which sentences to remove? On what basis? Before we know what the guidelines are we can’t really say,” Ghio said, stressing that what the minister had stated to Parliament consisted of an administrative process and not clear and transparent legislation.

Lovin Malta has reached out to the Justice Ministry for comment but had not received a reply by the time of publishing.

Public interest not the only consideration

Privacy lawyer Yasmine Aquilina said the right to privacy wasn’t an absolute one.

“It must be balanced against other individuals rights or those of the state,” Aquilina said, adding that it was for this reason that the GDPR provided for derogations to the right to be forgotten.

“This includes for exercising the right of freedom of information, for performance of a task carried out in the public interest, for archiving purposes or for the establishment, exercise or defense of legal claims.”

She noted that the publication of judgments was important for the Courts’ transparency and the public’s right to information, including for research purposes.

Aquilina added that it should at least be made clear when a searched judgment has been deleted from the online portal.

Aquilina also pointed out that the courts’ website lacked a clearly accessible privacy policy, meaning it was “unclear which legal basis is being used for the processing of such data and whether or not the right to be forgotten may actually be applied”.

Do you think court sentences should be removed in some cases?