Compared To Past Leadership Wars, The PN’s Current One Is A Water Balloon Fight

Whether taking the form of a mourning cry from long-time supporters of the party or barely hidden glee from its opponents, the PN’s leadership woes seem unprecedented or even unique to many observers.

But the reality is that the PN’s current troubles serve to teach us just one thing: how effective political parties, even local ones, are at obliterating the stories of their past internal strife. Yes, the current leadership battle is messy, and some blows have been struck below the belt, but it’s still a relatively benign affair. Here are a few other power struggles within Maltese politics, many of which much larger, messier and dirtier. Just imagine if Facebook Live was around then!

1949: Paul Boffa and Dom Mintoff

Paul Boffa managed to win a Maltese General election by the greatest ever margin, amassing nearly 60% of the vote in 1947. But just three short years later, all that came tumbling down following a severe showdown with his deputy. Mintoff has been undermining and humiliating Boffa for years: one well recorded episode has Mintoff dictating what the country’s negotiating position with the Crown Government should be to Boffa instead of the other way around. When Boffa stood his ground, an infuriated Mintoff resigned his Ministerial post, but remained in the Labour party and started to organise his own mass meetings, during which he often said things like “nfarrak lil Boffa”.

Eventually, Mintoff decided to up the ante, and accused Boffa of an incestuous relationship with his daughter. And then, in a grand finale, on 9th October 1949, during a Labour General Conference, Mintoff stood up defiantly, thanked Boffa for all he had done, and led a no confidence vote against his leader. In sheer disgust, the members loyal to Boffa, comprising around half of the hall, left, with the remaining half voting to remove him.

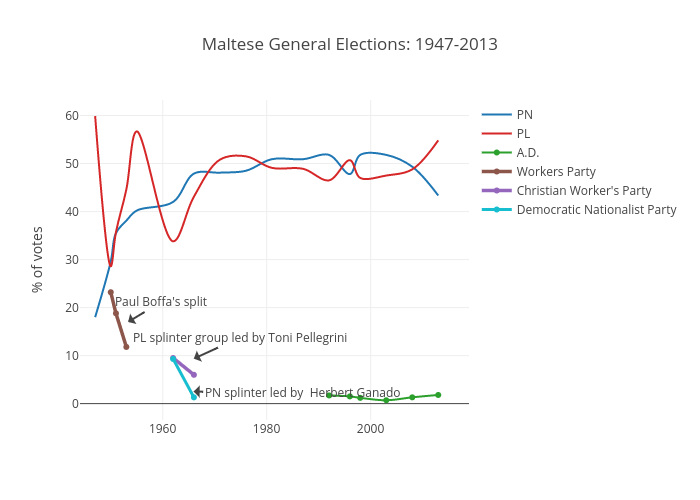

The Labour Party was split in two. Boffa would never contest an election on a Labour ballot again, forming his own separate “Worker’s Party”, which won 23% of the vote in 1950. He also won subsequent elections in 1951 and 1953, and formed part of a coalition government with Borġ Olivier’s Nationalist Party.

Eventually as time passed, enough people forgot or forgave Mintoff’s coup and he succeeded in reuniting the party almost entirely, save for a handful of hardened Boffa loyalists.

1950: Enrico Mizzi and George Borg Olivier

Although not a leadership battle per se, with Mizzi dying in office, when Borg Olivier succeeded him, he took the party on a drastically different direction. It’s hard for us nearly four decades after his death to understand just how liberal Borg Olivier was – suffice to say he was laying the foundations of a secular state at a time when Dom Mintoff was still signing political manifestos with sentences like “”in all actions take inspiration from the teachings of Our Lord Jesus Christ, as propounded by the Roman Catholic Church”.

In 2011, Fr. Peter Serracino Inglott who had a longstanding acquaintance with Borg Olivier, insisted “he would have preferred the name of his party to be Liberal rather than Christian Democrat, but not at all because he saw any intrinsic opposition between the two names… Borg Olivier used to stress that John Locke, generally deemed the founder of Liberalism as a political ideology, claimed that he derived his inspiration from the Epistles of St Paul, on which the English philosopher spent the last years of his life writing a commentary.”

This philosophy of life was very different from Enrico Mizzi’s devout Catholicism and conservatism, and at the time people were unsure of how Borg Olivier would make it work. But somehow he did, and he also succeeded in taking the PN away from an Italianate, nearly fascist past and transforming it into a force for modernism and stability at a time when the country deeply needed one.

1959: Herbert Ganado and Borg Olivier

Borg Olivier’s leadership of PN however was not without criticism, and one of the most substantial dissenting voices belonged to Herbert Ganado, a lawyer and author of Rajt Malta Tinbidel. Ganado questioned whether Borg Olivier was strong enough to contain and rebuke Mintoff, who had evolved into a dominating and intimidating figure in several Parliamentary screaming matches. But more importantly, Ganado felt that Borg Olivier’s proposals for facets like social care were much poorer than Mintoff’s, who he regarded to be leagues ahead of the PN in these spheres.

And so, Ganado gave rise to the “Democratic Nationalist Party”, which was an amalgam of the best of the PN’s ideas mated together with Mintoff’s social and welfare vision. Ganado’s party won 9.3% of the vote in 1962, but soon lost relevance after one election cycle. Borg Olivier successfully managed to reconcile most of the party, and Borg Olivier made it a point to attend Ganado’s funeral to cement that unity.

1961: Toni Pellegrini and Mintoff

Toni Pellegrini (center) in between Mabel Strickland and Dom Mintoff

During the height of the crisis between the state and the Catholic Church, Mintoff’s party became anticlerical, alienating a small but not insignificant number of traditionally Labour voters. Mintoff also alienated other members, including general secretary Toni Pellegrini. Having had enough in 1961, Pellegrini resigned, and formed his own “Christian Workers’ Party”, which balanced pro worker polity with a pro-church and decidedly anti-Communist position.

For the second time in 12 years, Labour was again split. In the 1962 election, Pellegrini managed to secure 9.5% of the vote, earning his party four seats in Parliament. However, over time, Mintoff managed to reabsorb most of this group too, and the Christian Workers’ Party was dissolved in 1966.

1977: Borg Olivier vs the Newcomers

Subsequently: Eddie Fenech Adami vs Guido de Marco

Following two successive electoral defeats and Borg Olivier’s fall from grace, new faces in the PN like Eddie Fenech Adami, Guido de Marco and Censu Tabone attempted to wrangle it away from a path of irrelevance (sound familiar?).

In failing health, and following an impromptu meeting in de Marco’s Hamrun home smelling of subversion, Borg Olivier relented to stepping away from the PN. But this was just the beginning. De Marco has preceded Fenech Adami in the party; and Fenech Adami, who didn’t secure a seat via an election, was only co-opted into the party due to pressure by De Marco. What’s more, he also had an unshakable ambition to become leader, and on realising that Fenech Adami did too, he began to openly patronise him. While at first de Marco didn’t regard Fenech Adami as a threat, he grew increasingly worried as the campaign progressed, going to far as to urging Ugo Mifsud Bonnici to contest the leadership election in a bid to split Fenech Adami’s supporters.

Mifsud Bonnici declined, and Fenech Adami won, receiving an overwhelming two thirds majority of the vote. More pertinently however, he decided to keep both de Marco and Censu Tabone not only in the party, but in public roles.