How Protected Are Malta’s Trees? An Analysis Of Our Laws And Loopholes

The Trees and Woodland Protection Regulations go a long way in protecting trees in Malta, their mere existence is a clear example of why the relationship between legislation and the environment is paramount to the protection of our ecosystems and natural environment.

The Trees and Woodlands Protection Regulations (SL 549.123), which was updated in 2011, is a fundamental instrument in preserving Maltese trees and protecting them from unregulated destruction and greed but question remains whether the appearance of further protection is backed up by actual advancements in legislation.

According to the ERA official website, the regulations are accredited to adding “30 new protected species” to the previous 60 species that were already protected in 2011. In reality, it is only through a thorough comparison of the separate pieces of legislation that one can find concrete proof of further protection.

On the surface, the current regulations give the impression that if a tree is protected under the law, it cannot be cut down. In reality, 38 species of these protected trees are protected everywhere and can under no circumstances be removed, leaving the remaining 53 subject to removal in certain situations.

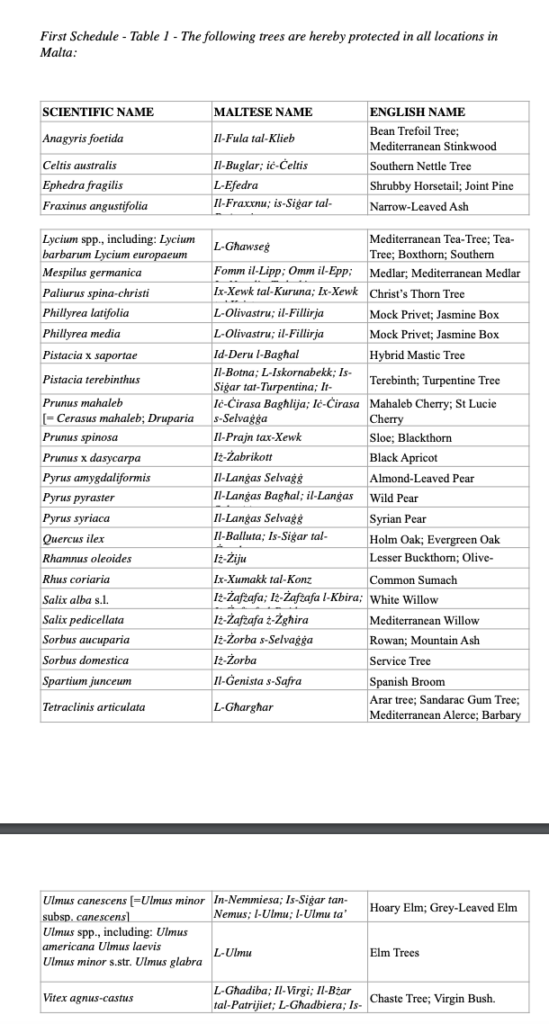

The First Schedule is a comprehensive list of all the species of trees in Malta that are “protected in all locations in Malta”, giving trees the necessary protection even when it comes to cases of development, construction and road-widening. The First Schedule therefore can be said to legislatively provide adequate and definite safeguarding of our environment with no terms and conditions attached to that protection.

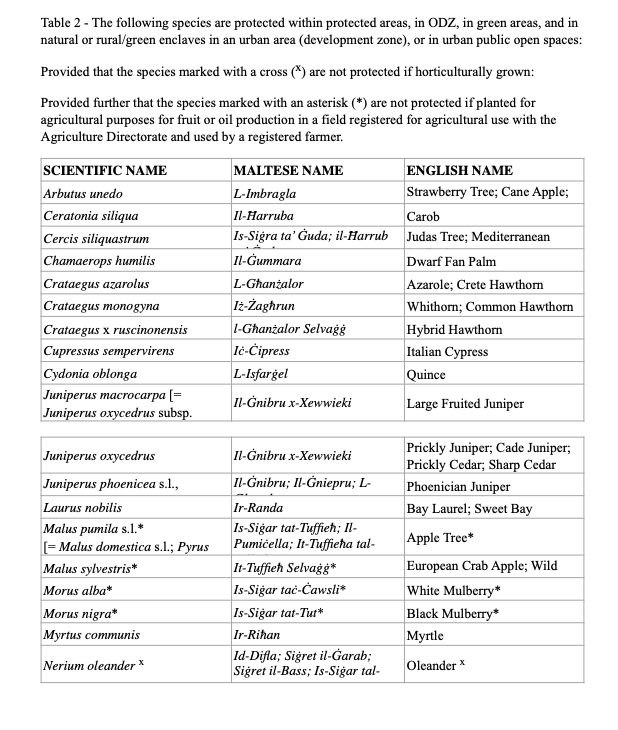

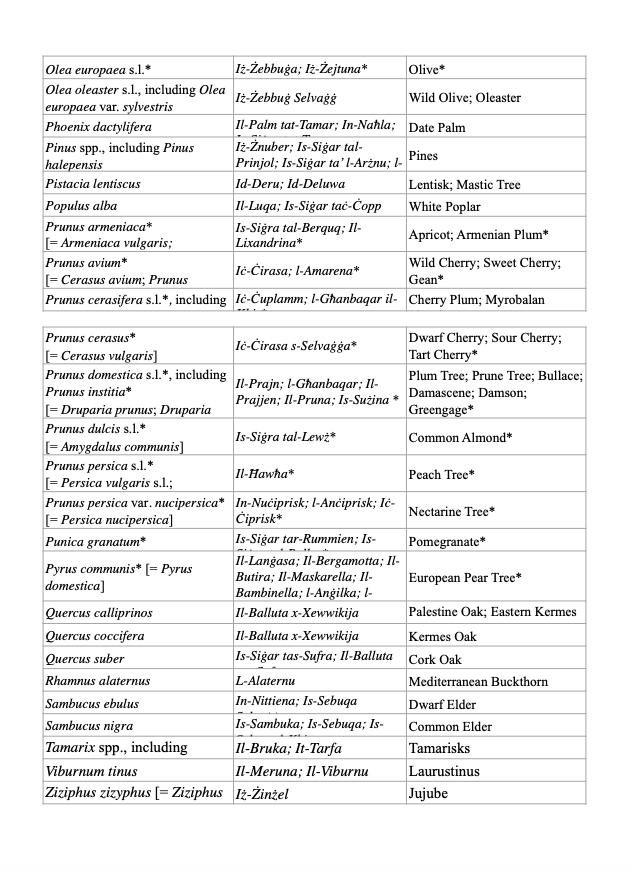

The Second Schedule, on the other hand, comes with a set of requisites that could be considered in practice as removing the protected status of these trees.

ERA’s website states these “species are protected within protected areas, in ODZ, in green areas, and in natural or rural/green enclaves in an urban area (development zone), or in urban public open spaces” but fails to mention that this protection could easily be retreacted if the criteria are satisfied.

If a tree is technically labelled legally as a protected species under the Second Schedule but isn’t located in the designated areas found above, it can be removed by law. This creates a dangerous state of play as the protected species of trees which are most in danger aren’t those found in designated safe areas but rathers ones that are on the sides of roads or in the vicinity of proposed development sites.

In reality, the majority of trees added by the reintroduced regulations were placed into the second table, with only two added to the first. Although this could be considered as an improvement to the previous 2011 list, categorising these species into the second table ultimately offers them little protection from the rise of development in Malta.

Another condition of definite importance when considering the damage being done through the removal of trees in Malta is the clause further removing protection to all species of trees that fall under the second table but are considered “horticulturally grown”.

Legally this could have rather ranging implications when considering that the definition of a horticultural plant is general and includes considering a tree as an “ornamental construct”. This categorisation could mean the removal of a tree’s protected status merely based on the fact that it was planted horticulturally, regardless of where this tree presides.

The potential danger falls in the legal definition of horticulturally-grown trees as “planted trees that are grown through horticulture and in artificial environments such as agricultural land, private gardens, roadsides and paved areas, and excludes trees in protected areas or in areas outside the development zone growing in their natural environment, whether originally planted or not.”

Using the definition given to us by the law, it is evident that roadside trees – even if protected under the Second Schedule – can be subject to removal because of their horticultural categorisation. Certain species are also stripped of their protection if they were planted for what the law describes as “agricultural purposes” and therefore the question arises whether the protection for many of these species is at the discretion of the interpretation of the law.

What can be clearly seen in this regard is that although the regulations protect in all circumstances the species of trees found in the first schedule, those in the second one come with terms and conditions allowing the destruction of certain species in cases of construction and development.

The ERA website also mentions that the new regulations add protection to “mature trees over 50 years of age that are found in urban, public, open spaces” irrespective of their species. The main difference between the 2011 version of this provision and the 2018 version is that now protection of these mature trees is extended to “urban public open spaces”.

A critical observation of these regulations is fundamental when we begin to look at what the government is actually allowed to do in the name of public interest. Although areas designated as ODZ, green areas and urban public spaces seem to foster concrete protection for the 90 species mentioned, the areas where these trees seem most vulnerable are often not protected, these areas being development zones and roadsides.

ERA, in its functioning, has many tools in its legislative arsenal to combat the eradication of trees; these include not only the Trees and Woodlands Regulations, but also the Guidelines on Trees, Shrubs and Plants for Planting and Landscaping in the Maltese Islands (2002), the Guidelines for the Reduction of Light Pollution in the Maltese Islands (2020) as well as the Natura 2000 sites management plans (2017).

Even with the existence of this vast legislation, the public interest decided upon by the government in Malta often supersedes the environment.

It is important to consider that in reality most protected species cut down are done with an issued permit from ERA; often these permits come with certain conditions and are often disregarded. In January 2020, a group of almond trees were completely destroyed; the permit only allowed the transplanting of these trees but as often is the case, Infrastructure Malta “deviated” from the original permit.

ERA’s ability to act impartially could be hindered considering that Article 13 of the Trees and Woodland Regulations allows it to permit the uprooting of even first-schedule protected species. What is often happening in Malta is not the illegal uprooting of these trees by Infrastructure Malta or the Ministry for Transport and Infrastructure, but instead the continued allowance of such destruction through the means of a permit. This was the case in Dingli where numerous carob trees were removed completely legally, by means of an ERA permit.

The same happened with a group of 100-year-old protected oak trees near the Lija cemetery. Although the Trees and Woodland Regulations merit progress, they are repeatedly halted in their tracks by their own design. The law gives little power to ERA when it comes to protecting trees outside the designated areas, and even in those areas, ERA is clearly not allowed to operate as freely as needed because public interest as seen by the government most often prevails.

Times of Malta has estimated that 450 trees will be the victim of the Central Link project in particular. The Environment and Resources Authority regulations state that this would mean Infrastructure Malta would have to plant at least over 1,400 as compensation, but the unfortunate reality is that the government has only pledged to plant around 750 trees.

Again the law seems to be undermined by the demand for progress at all costs; this particular instance saw several mature trees cut down at night without notice to the general public through the permit application. This all highlights a lack of enforcement when it comes to the government:

In terms of ERA’s role as legislator, it is notable that the Minister is the principle motivator and has a responsibility towards the environment and government agenda. This can be the reason why government institutions such as Infrastructure Malta and the Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure seem to continuously cut corners in implementing these laws and pursuing punishment after they are not adhered to.

In the case of two landmark trees being cut down in Balzan in 2018, the trees were said to have been damaging the road’s infrastructure. The law makes it very clear that trees, even if protected, are subject to removal if they begin to damage certain “structures or features of natural or cultural heritage value”. However, a roadside being considered of such value could be considered quite a strange interpretation of the law.

This raises another issue – interpretation. In this case, like many other instances, these regulations were loosely interpreted and therefore, unlawful actions justified by the competent authorities.

On a positive note, many of these regulations didn’t even exist up to a decade ago and ERA itself represents an awakening in Malta when considering the environment. Environmental awareness is clearly on the rise and the value of these trees is being recognised by more people every day.

Unfortunately, many abuses are occurring as a result of poor enforcement and government intervention within ERA itself. A large amount of legislation present can also be considered confusing to laymen and this is in itself an issue, because the average person should be able to understand the law and apply it.

Ordinary people should be able to hold their representatives accountable especially on determining issues in their lives, such as environmental conservation as well as air pollution. This is made extremely difficult with the current legal format and therefore a unification of many of these legislative documents published by ERA is very possible and would simplify these regulations whilst maintaining their substance.

Another resolution to the issues at play would be more impartiality when it comes to ERA itself; the government cannot continue to have such a prominent role, through the Minister, in an authority designed to regulate it.

Trees are fundamental to all life and through more comprehensive and foolproof legislation, more thorough enforcement, more transparency when it comes to permits and changes in legislation and more incentive to obey the regulations, we can protect and begin to rehabilitate the Maltese Islands’ natural environment.

Should Malta update its tree protection laws?