How the Palestine-Israel Conflict Has Spilled Into Malta Over the Years

On 1 May 2025, a vessel carrying humanitarian aid to Gaza and partially organised out of Malta was struck by an unmanned aerial vehicle in the eastern Mediterranean. No group claimed responsibility, but all the hallmarks of an Israeli operation were there: strategic precision, high-grade military equipment, and silence.

To many, the incident seemed like a shocking anomaly — a Maltese-linked ship targeted in a Middle Eastern war. But history tells a different story. Malta has, on more than one occasion, found itself on the edges of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Sometimes as a mediator, sometimes as a backdrop — and occasionally, as the stage for bloodshed.

Here are a number of moments when the Israel-Palestine conflict reached Malta.

The Hijacking of EgyptAir Flight 648 – November 23, 1985

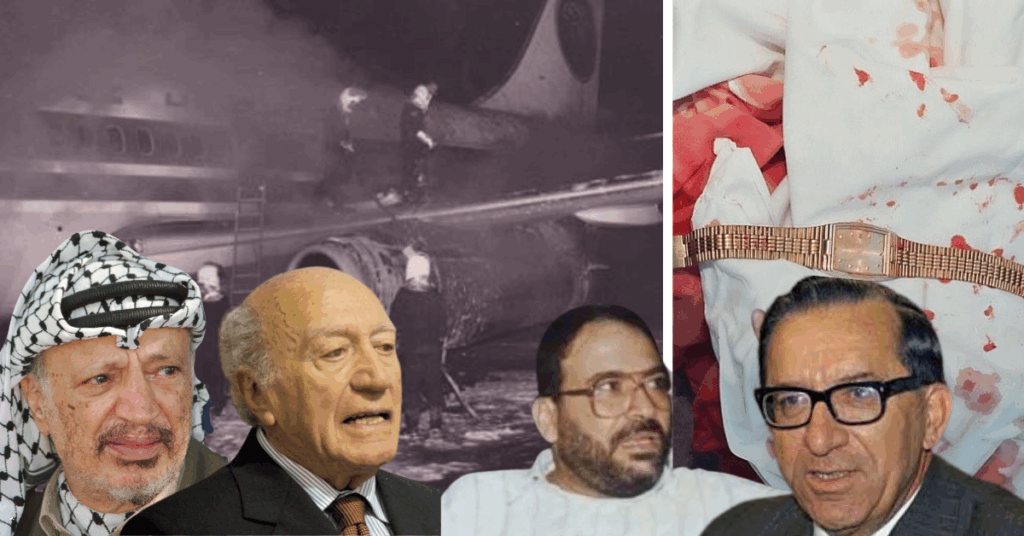

The most catastrophic of all was the hijacking of EgyptAir Flight 648. Three members of the Abu Nidal Organisation, a radical Palestinian splinter group, seized control of the flight en route from Athens to Cairo and forced it to land in Malta.

The climate was tense: Egypt had signed peace with Israel, becoming a target for militant Palestinian groups. Abu Nidal, opposed to both the PLO and peace with Israel, often launched attacks intended to destabilise Arab governments seen as conciliatory.

After the plane landed at Luqa airport, the Maltese authorities negotiated with the hijackers, but a standoff ensued. Egyptian special forces stormed the plane 24 hours later, using explosives to enter. The result was disastrous: 60 people were killed, most of them during the raid.

The event caused severe diplomatic tension between Egypt and Malta. Dom Mintoff, who had pursued a non-aligned foreign policy, denounced the operation as a massacre.

KLM Flight 861 – November 25, 1973

Two days after another hijacking incident in Dubai, three young Arab men hijacked KLM Flight 861, a Boeing 747 with 247 passengers en route from Amsterdam to Tokyo. They took control over Iraqi airspace and demanded it be flown to multiple destinations.

No country would accept the aircraft until Malta allowed it to land at Luqa Airport. Prime Minister Dom Mintoff personally negotiated with the hijackers, reportedly telling them the aircraft could not physically take off with both a full load of passengers and the 27,000 gallons of fuel they were demanding.

Eventually, most passengers and all crew were released. The plane left Malta with just 11 people on board and flew to Dubai, where the crisis ended without bloodshed. The incident was part of a broader wave of Palestinian-linked hijackings in the 1970s, intended to draw global attention to their cause. Malta, whether by geography or neutrality, became an unwilling participant.

The Assassination of Fathi Shaqaqi – October 26, 1995

In 1995, Malta became the site of a covert assassination. Fathi Shaqaqi, the founder of Palestinian Islamic Jihad, was gunned down outside the Diplomat Hotel in Sliema by two assailants on a motorbike. He had been travelling under a false identity after a trip to Libya, where he reportedly secured funding from Muammar Gaddafi.

Israel never claimed responsibility, but intelligence reports and later investigations pointed to Mossad. The operation bore all the agency’s hallmarks: a silenced weapon, no forensic trail, and rapid extraction. Shaqaqi had been blamed for a string of suicide bombings in Israel and was considered one of the most dangerous Palestinian militant leaders at the time.

The killing sent shockwaves through Palestinian circles, briefly paralysing the Islamic Jihad leadership. For Malta, it was a grim reminder of how the quiet neutrality of a Mediterranean island can still make it a player — or a pawn — in much larger conflicts.

A Tradition of Sticking Their Necks Out

Beyond these incidents, Malta’s involvement in the Israel-Palestine conflict hasn’t always come by force. At times, it came from conviction.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Prime Minister Dom Mintoff emerged as a fierce advocate for Palestinian rights, granting the PLO official status in Malta and repeatedly condemning Israeli aggression. His non-aligned stance, combined with his ties to Yasser Arafat and Muammar Gaddafi, brought Malta under close scrutiny from the West — particularly the United States.

Declassified diplomatic cables show that Mintoff was viewed by the CIA and U.S. State Department as unpredictable and dangerous. American intelligence closely monitored Malta, suspecting that it was being used as a communication channel and logistics base for anti-Western actors, including Palestinian militants. Washington also resented Malta’s refusal to allow U.S. Navy ships to dock — a stance Mintoff maintained as part of his broader anti-imperialist policy.

Years later, President Guido de Marco would also make headlines for his firm support of Palestinian dignity. During the Israeli siege of the West Bank in 2002, de Marco reportedly phoned Yasser Arafat daily. He urged calm while expressing solidarity — even sending personal messages through European leaders urging Israel not to harm the Palestinian leader.

De Marco also promoted people-to-people dialogue, hosting events in Malta that brought young Israelis and Palestinians together for reconciliation programmes. His efforts were quieter than Mintoff’s, but no less sincere. Malta, through him, maintained its identity as a country willing to advocate for justice — even when it meant stepping outside the Western consensus.

A Changing Posture

The 2024 drone strike may have surprised many, but perhaps more striking is the contrast in how Malta’s leadership now responds to such incidents. Where past prime ministers and presidents were unafraid to take clear, and often controversial, stances on Palestine — even at the risk of straining ties with major powers — today’s political class has adopted a far more cautious tone.

There were no fiery speeches in Parliament, no declarations of solidarity, no Maltese official standing on the international stage to condemn the attack or demand accountability. The country that once gave the PLO diplomatic space, that sent personal messages to protect Arafat, that risked U.S. ire in the name of principle, now finds itself watching from the sidelines.

In a world where neutrality is increasingly transactional, Malta’s historical willingness to take moral positions — especially on Palestine — stands in contrast to the current climate of quiet diplomacy and risk aversion.