L-Interdett: How Malta’s Church Made Supporting The Labour Party A Mortal Sin

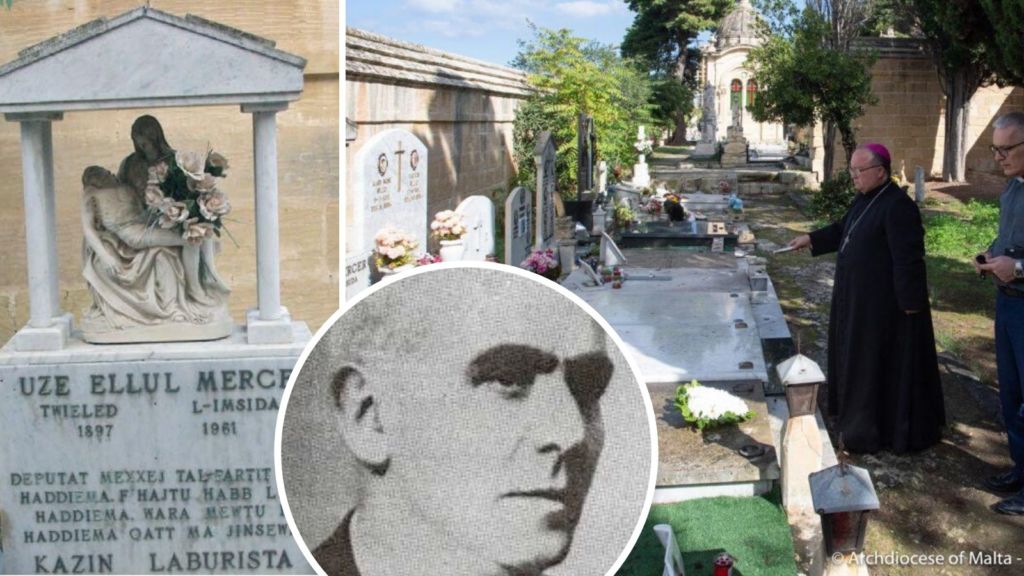

The sight of the Archbishop begging for forgiveness while blessing the tombs of a once-unconsecrated section of the cemetery has brought a renewed focus on one the darkest periods in Maltese history, the interdiction of the 1960s.

A war that shed no blood but left everlasting wounds, the interdiction (l-interdett) saw the church declare that supporting the Labour Party was a mortal sin.

Remember, this is not the Malta it is today. Even though the Church still holds some influence, back then it and conservatism reigned supreme. Homosexuality and adultery were illegal while women had only been granted the right to vote a decade prior.

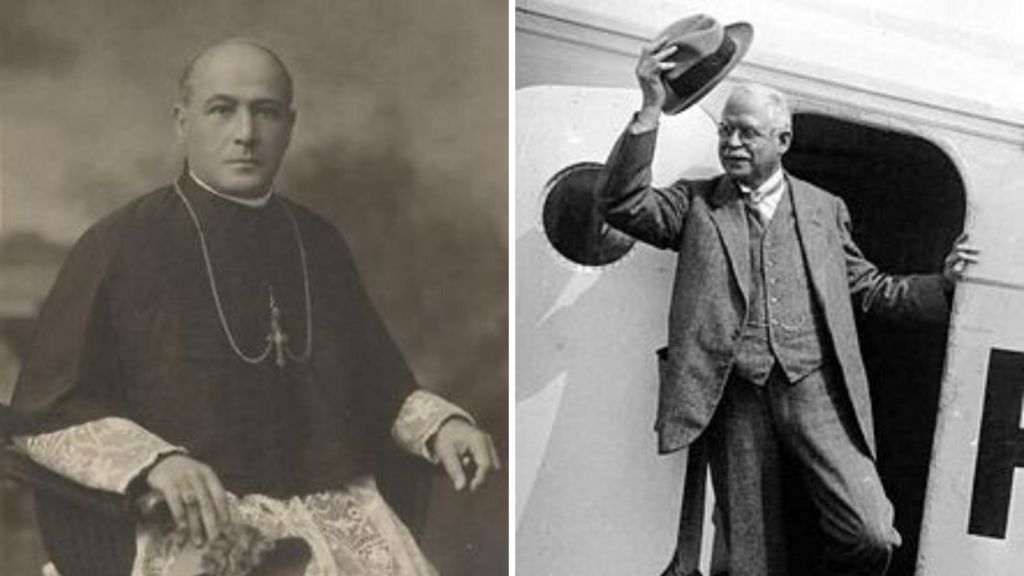

Being cut off from the Church inflicted social shame on Labour families, while two men from Cottonera, former Prime Minister Dom Mintoff and former Archbishop Mikiel Gonzi, jostled for ideological supremacy on the islands.

The period, while so intrinsically important to the development of Malta as a nation, is seldom researched or discussed. Lovin Malta took a look at the interdiction, what lead to it, and how it informs the current political climate.

The Dark Years: The Interdiction (1961-1969)

After Mintoff’s continued calls for a separation of Church and state, Archbishop Gonzi ‘interdicted’ supporters of the Labour Party on 17th March 1961, specifically, the Party’s Executive Committee, readers, distributors and advertisers in the Party papers and voters and candidates of the Party.

The anti-religious aspects of socialism were also highlighted, the situation was exacerbated with Labour’s decision to develop relationships with the Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Organization (AAPSO). Meanwhile, fears that Mintoff was a closet communist and would accept aid from the Soviet Union further compounded the issue.

Those ‘interdicted’ could not receive the sacraments and, when they died, were buried in unconsecrated ground, in a part of the cemetery popularly called by the pejorative term Il-Miżbla (the dump).

Several Labour Party activists were buried there, including Deputy Leader and highly-regarded author Ġużè Ellul Mercer.

Some people weren’t even allowed to get married in church, with only the sacristy reserved for couples with links to the Labour Party, like what happened to former Minister Joe Micallef Stafrace.

“I met Mgr Gonzi, and he had all my writings laid out on his desk. He told me that if I ‘converted’ he would even have officiated the wedding ceremony himself at the Palace.”

“When I said I felt I had done no wrong, he insisted I could only get married in the sacristy, even denying me the right to get married in a chapel. I later learnt that several priests had urged my wife-to-be to leave me. Can you imagine that?” Micallef Stafrace said in a Times of Malta interview back in 2011.

His wedding, he explained, was humiliating, with a group of Catholic youths chanting politically-loaded hymns outside the Church and passing snide remarks, questioning why such a beautiful bride was marrying a Labour executive member.

Kindness, however, came from unlikely places. Despite forming part of the Christian Democratic Nationalist Party, former President Guido de Marco took an active part in ensuring the wedding was a success, one of the many instances where the PN heavyweight directly intervened.

The era, obviously, was defined by its tense political climate, with supporters of the interdiction regularly humiliating Labour activists.

Labour Party rallies were also often disrupted by continuous churchbells ringing and whistling and other deliberate noise by Catholic laypeople, while church sermons were predominately used to damn their political rivals.

One recording showing Mintoff yelling above the church bells still exists on YouTube today.

The crisis would lead to Mintoff issuing his six-point plan for independence, which included the separation of Church and State, the acceptance of civil marriage, the removal of the Church from censorship issues, a parent’s right to exempt their children from religious teaching at school, the right of all citizens to be buried in the cemetery, and the empowerment of police to enter churches to stop bells from ringing.

Interdiction would only be lifted in 1969.

At first, the decision yielded Gonzi’s desired result, with the Labour Party losing 7 parliamentary seats and dropping by more than 20% in the 1962 general election as the country veered towards independence.

However, this would not last. Dom Mintoff would quickly recover, with the Labour Party eventually taking control of the government by 1971, holding onto power until 1987. In his tenure, sodomy, homosexuality and adultery were decriminalised.

The Prelude: The First Interdiction

In a sign for things to come, Monsignor Gonzi (who was then Bishop of Gozo) played a part in the interdiction of former Prime Minister Gerald Strickland. On 1st May 1930, the then Bishop of Malta Mauro Caruana declared that whoever voted for the Constitutional Party and its former coalition partner, the Labour Party, committed a mortal sin.

Anyone who read Strickland’s newspapers, printed by Progress Press, also sinned.

The core of the issue was also religious. Strickland’s papers and party regularly criticised the Church, pushing for Malta to become a secular state.

The clash between the Church and political party eventually led to the suspension of the Maltese Constitution, with authorities declaring it was impossible to hold a free and fair election, with the threat of mortal sin looming large.

In a blow to the Church, Strickland was chosen to head the caretaker government until the situation returned to semi-normality.

The Church would have the last laugh, with the Constitutional Party crumbling in the next general election, losing five seats. Following a brief hiatus in the mid-40s, the party would become obsolete in the political scene by 1953.

The Build-up: Integration And Dockyard Riots

While troubles may have kicked off long before, relations between Gonzi and Mintoff deteriorated during the integration campaign of the mid-1950s. With Mintoff pushing for Malta to become part of the United Kingdom, Gonzi feared that the Catholic Church would be lost in favour of Anglicanism.

An interdiction was not called. However, the Church still asked voters to either vote ‘no’ or abstain, floating banners with “Meta tivvota Alla jarak u jiġġudikak” (When you’re voting God will watch you and will judge you).

Gonzi’s success is debatable. While Mintoff won the referendum with close to 80% of vote, less than 60% went to the polls, while integration was dumped in favour of independence.

Things got worse in 1958 during the nationwide protests and unrest over the dockyard closure. Gonzi quickly condemned both the protestors and the Labour Party for supporting them, which in turn drew criticism of the Church for failing to attack the harsh conditions imposed by British colonial authorities.

The Aftermath: How we live with its legacy

The effects of the interdiction can be felt today. Why would a lifelong Labour Party supporter even consider switching to the catholicly-aligned PN, when they have friends and family members, who were oppressed and ostracised by the church?

Take a look around any lifelong Labourite’s home (particularly of the Mintoffian sect); you’re much more likely to see a picture of the former and current Prime Minister than you are of any religious figure.

It’s also partly why most Labour Party supporters view the Church’s few forays into political commentary as sceptical, with even the Archbishop subject to intense criticism and allegations of bias whenever he comments.

The animosity of the other side would spill over into Mintoff’s tenure, where Nationalist Party supporters became oppressed, creating a diametrically opposed group of diehard supporters.

Unfortunately, an inability to critically analyse the most divisive periods of our history and simply focus on the actions has left wounds unhealed just as the country deals with a new identity crisis following the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia.

In Malta, we never learn, just argue.