Malta Could Have A Metro In Ten Years… If We Only Follow This Architect’s Well-Detailed Plans

Ten years. That’s all the time it could take for a metro to actually start functioning in Malta, a long-term solution for the island’s perennial traffic woes.

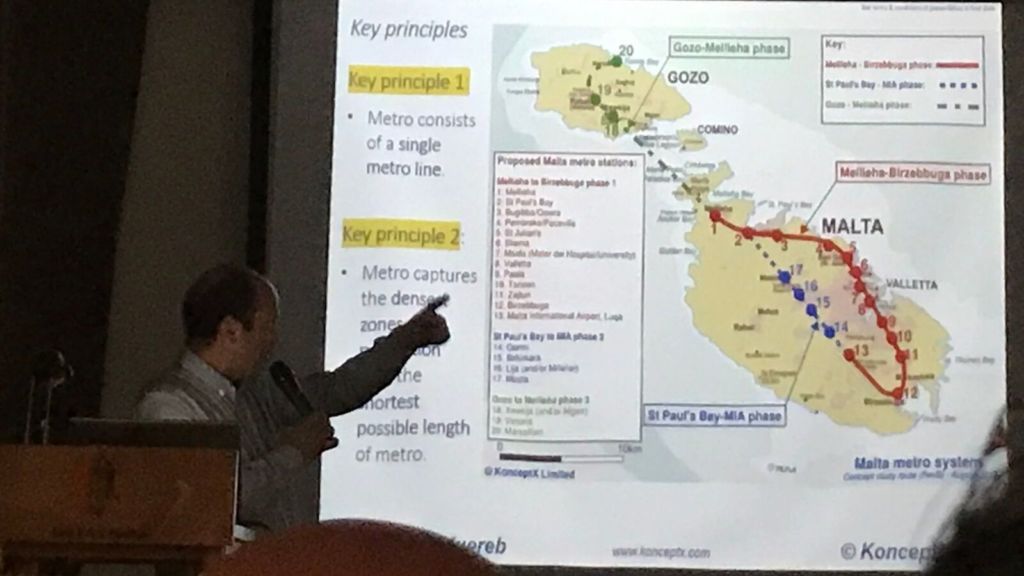

Maltese architect Konrad Xuereb and his firm KonceptX have worked on some major projects worldwide, such as the Al Bahr Towers in Abu Dhabi and the Lochnagar Bridge in London, and they’ve now turned their focus towards designing a financially feasible metro for the Maltese Islands.

Around 60 people turned up to listen to Xuereb’s plans at an event organised by the environmental NGO Din l-Art Ħelwa last night… and they weren’t left disappointed.

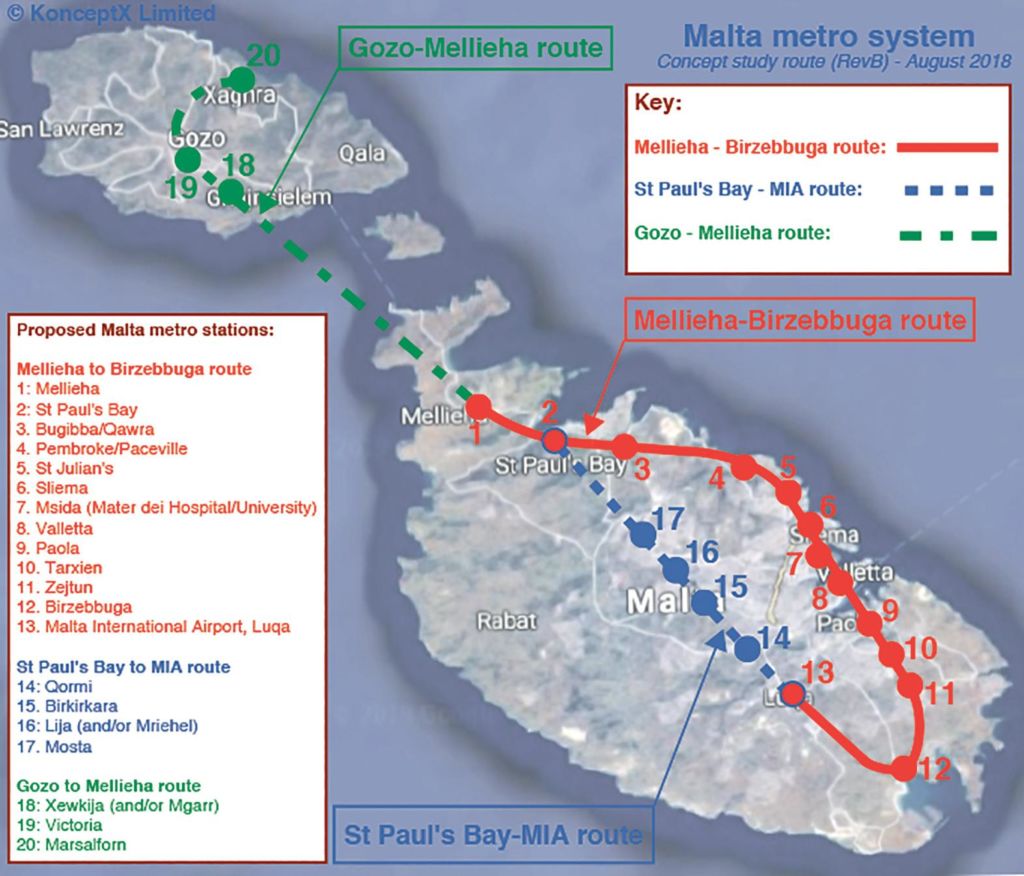

Xuereb has envisaged a single 50-kilometre metro line connecting the major hubs of Malta and Gozo, with around 40 trains in operation, feeder shuttle buses connecting the towns and villages left without a metro to the nearest station, and rental bikes at every station based on the ‘Boris Bikes’ of London.

How the metro will work

Xuereb has projected it will take five years for all the necessary environmental, archaeological, financial and social studies to take place, after which construction will be able to begin.

The first phase of the project will connect the airport to Mellieħa and make stops at Birżebbuġa, Żejtun, Tarxien, Paola, Valletta, Mater Dei, Sliema, St Julian’s, Pembroke, Buġibba, St Paul’s Bay and Mellieħa. Xuereb has estimated this line will take around five years to build, which means people will be able to start using the train by as early as 2029 if the studies start from now.

Work would start on the second phase, connecting the airport to St Paul’s Bay via Qormi, Birkirkara, Lija/Mrieħel and Mosta. After two years, the most ambitious part of the project will commence, linking Mellieħa to Gozo with stops in Xewkija, Rabat and Marsalforn. After five years, the entire project will be complete.

Xuereb has estimated the project will cost €4 billion to construct and has proposed that the government secures €675 million in EU funds through the TEN-T programme to connect the continent, release €1.57 billion in bonds with a 20-year maturity, and make up for the remaining €1.75 billion through public funds.

While this will cost the public purse a hefty €175 million a year, Xuereb wisely noted that this is not that much more than the €100 million a year the government is currently spending on the widening and reconstruction of roads.

And, unlike the roadworks, the metro have long-term financial and environmental benefits.

Xuereb kept his financial calculations conservative, assuming only 25% of residents and tourists will use the metro for a return trip everyday, which makes the results even more striking.

If Malta’s population grows by 8% to 525,000 by 2035 and tourist numbers remain stable at 2.5 million a year, some 53 million metro rides will be undertaken every year. If each trip costs €2, the total revenue from ticketing will be €240 million a year. Add an estimated €50 million per year in advertising revenue and €10 million in leasing out retail space at stations, and the total annual revenue will rise to €300 million.

Xuereb has estimated maintenance costs at €75 million, energy costs at €15 million, salaries and operating costs at €40 million and contingency costs at €20 million, which means the metro will make an annual profit of €150 million. Within a matter of time, the government will be able to make up for the construction costs.

This is over and above the reductions in traffic, the environmental benefits of building underground instead of widening roads, and the healthcare benefits of reduced car emissions.

Isn’t Malta too small for a metro though?

Xuereb has debunked that argument by observing that Lausanne, Rennes, Brescia and Catania, European towns with a much smaller population than Malta, all have functioning metro systems.

The Wallasea bird sanctuary, built out of construction waste. Photo: Crossrail

And what about the construction waste?

This has become a pressing issue in Malta after all, with the government and developers coming to grips with the fact that there’s simply not enough space to dump it in.

Xuereb’s proposal is clear and to the point – land reclamation for environmental purposes. As examples, he has pointed at the Wallasea bird sanctuary in the UK, built from the construction waste generated by a railway project, the Kagoshima Nanatsujima solar farm in Japan, and the London Array offshore wind farm. The project could therefore hit two birds with one stone, setting up a well-needed mass transport system and in the process creating a peaceful nature reserve or generating cleaner energy.

“I felt it was my duty to conduct a study and publish the findings to show that yes, there is an alternative,” Xuereb said when taking questions the end of his presentation. “A year and a half ago, people would have called this proposal crazy but now they’re agreeing that we can’t keep on widening our roads forever.”

“We must stop widening our roads. It will be painful for the next ten years and we might have to catch the bus, but we’ll know that in ten years we’ll have a system that works. If the government says we cannot drive on certain days, then so be it, but we’ll know we have a solution for the future.”

As Xuereb finished his presentation, he was met with rapturous applause and people crowding him to praise him and find out more details. This was no pie-in-the-sky proposal from a commuter frustrated at getting stuck in traffic for the umpteenth time but a well-researched plan by an architect who has rubbed shoulders with the best in the business. It’s too early to get excited, and the government has yet to make its mind up, but this certainly looked, sounded and felt like the real deal.