Maltese Surgical Trainee: How The COVID19 Swab Test Works And Why It Is Important In Flattening The Curve

In the course of the last month, as a nation, we have become accustomed to putting on our televisions and smart devices every day at around noon to listen to the updates from Prof Charmaine Gauci with regard to the ongoing COVID 19 pandemic.

Every day Prof Gauci tells us about the number of new cases on our islands, the number of those who have recovered or, unfortunately, perished. However, emphasis is also placed on the number of swabs performed. Over 16,000 of these swabs have now been performed locally from the start of this pandemic. In a news conference on March 16th, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the head of the World Health Organisation (WHO), conveyed a simple message to all countries: ‘Test, test, test’.

He went on to explain that without testing, the virus will continue to sweep across the planet as cases cannot be isolated and the chain of infection cannot be broken. This theory has been proved both by our neighbours Italy, who were able to stop new infections entirely in the small town of Vo by repeated testing of its just over 3000 inhabitants, and in more distant nations in Asia, such as South Korea, where an aggressive ‘trace, test, treat’ policy was put into place early on, resulting in a dramatic flattening of the epidemic curve.

Over the last weeks, the world has paid tribute time over time to the heroes on the frontline of the pandemic; the nurses, doctors, cleaners, ECG technicians, physiotherapists, phlebotomists, and all those working tirelessly to put an end to the spread of this virus. As a doctor, I would like to thank the public for their endless support; and I would like to pay a special tribute through this article to the allied health practitioners in the molecular diagnostics lab who are working tirelessly during this pandemic to keep us informed.

Every day they not only have to expose themselves to the virus to test each and every sample rigorously, but they also endure numerous phone calls from us doctors calling to follow up on our patients’ swab results to guide us in our next steps of management.

I was fortunate enough to get to know this team of experts whilst reading for my Master of Surgery at the University of Malta last year. During this time, the team helped me conduct my research entitled ‘The Association of Helicobacter pylori and Colorectal Cancer’, funded by the Ministry of Education and Employment through the Endeavour scholarship scheme.

In this study, I looked into whether the bacterium H pylori can contribute to the development of colorectal cancer in the Maltese population and, whilst my study did not find such an association, little did I know how important the method employed to test this association would become in the following months. This method is called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

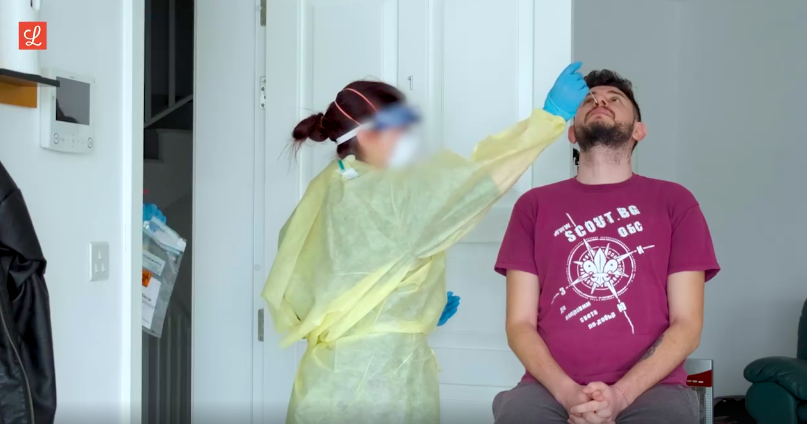

In the days following the publication of the novel coronavirus’ genomic sequence on January 12th 2020, a group of Chinese researchers began using PCR for detection and diagnosis of the virus. As we are now well aware, the test starts with a swab taken from the back of the nose, or the nasopharynx, of a patient suspected to be infected.

Genomic material extraction followed by PCR is then employed to search for the virus’ RNA. RNA is the molecule in which the novel coronavirus stores its genetic material, similar to the DNA us humans employ. The PCR test centres around the concept of DNA amplification. Therefore, an enzyme called reverse transcriptase is applied to the sample and if the virus is present its RNA is converted to DNA. This DNA is then amplified.

During a PCR run, DNA is fluorescently labelled, and the amount of fluorescence released during amplification is proportional to the amount of DNA amplified. The PCR machine’s software provides a graphical representation of the results, which is then interpreted by the biomedical scientists. The software result is translated as positive or negative depending on the amount of fluorescent signal released.

PCR is the most sensitive and rapid molecular test available for detecting microbes in clinical specimens, albeit with the disadvantages of equipment and consumables cost, loading times, inhibition of PCR reaction, possible contamination and tedious data analysis. It is important to keep in mind that if the virus is present only at low levels, which may be the case at the start or end of infection, PCR may still mark a sample as negative.

Moreover, the professional performing the swab must collect sufficient amounts of RNA; this requires them to insert the swab probe deep into the nose, which is likely to cause coughing and therefore it is imperative for the person performing the test to be adequately protected.

Besides PCR, another method being used is known as serology testing, or what we would commonly call a blood test. This test looks for antibodies in the blood stream. It allows for the identification of patients who were previously infected and have recovered and, therefore, do not have virus present in significant levels on swabbing.

The serology test uses what is called an antigen. This is a protein which targets the antibody created by the patient’s body to fight off the virus. The antigen sticks to, and captures, the antibody in the blood stream if present. This will result in light emission under the microscope and subsequently a positive result. Such a test is cheaper than PCR to run, but it may not always be as reliable.

Germany is preparing to make wider use of these blood tests in the coming weeks in a trial which will look mainly at four areas of Germany which were worst hit. Germany is another clear example of how widespread testing allowed for early identification of positive cases, and in turn the number of deaths and rate of infection in Germany rose much slower than in other major European countries.

I would like to emphasise once again the message I am sure you have all read by now; stay home, do not meet others, do not go outside unless it’s for food or health reasons. If you do go out, stay 2 metres away from people and wash your hands as soon as you get home. If you develop any symptoms call 111.

Take care of your mental health by following regular schedules and establishing objectives for each day; if you find yourself struggling in this regard call 1770. In the spirit of this article, I would like to once again thank the allied health practitioners in the molecular diagnostics lab. And finally, remind everyone that whilst we go to work for you, you need to stay home for us.

Keith Pace is a urology higher specialist trainee at Mater Dei Hospital