Revealed: Open-Source Data Shows Increase In Palumbo Shipyard Traffic After Rushed, Secretive Merger With MSC Cruises

A new investigative series launched in Malta has set out to see how increased shipyard vessel traffic and lax air pollution monitoring is causing perpetual health concerns for residents in Malta’s historic Three Cities.

Dozens of testimonies and new open-source data paint a grim reality where the citizens’ right to breathe clean air remains at risk – and accountability elusive.

This is a deep dive into the region’s ongoing air problem – and the implications which the numbers point at.

“A truck in your living room”: the residents speak out

When asked to share why he had first reached out to an activist group fighting against pollution, Peter*, a lifelong resident in Senglea, recalled how he had done so because of a strong smell of diesel fumes emanating from a privately-owned shipyard nearby. Peter is being referred to with a pseudonym at his own request.

Peter and his family have lived in Senglea for generations. Louis*, on the other hand, is a newcomer – he moved to Senglea around three years ago. When speaking to reporters, Louis said that there is “no way” he leaves any of the windows in his living room open.

“It feels like parking a truck in your living room with the engine running,” he said.

The activist group which Peter reached out to is known as ‘Azzjoni: Tuna Artna Lura’ (literal translation: ‘action: give us our land back’), or ATAL. Louis is one of the group’s newest members. Over the last few years, ATAL’s limited resources have been diverted towards an awareness campaign about air pollution generated by Palumbo Shipyard’s operations.

The second time Peter reached out to the group occurred just a few months after he had spoken to them. This time, it was a very stark visual reminder of the industrial activity going on a few hundred metres away from his home.

“I went out to dry my clothes and could literally see soot dust falling off of them, it was falling off the clothes like raindrops from the sky. It was like someone was burning tires. I reached out to the coalition and they told me to call the Environment and Resources Authority (ERA) and file a report,” Peter said.

“I called the ERA and they told me they were aware of it, but then heard nothing at all from them,” he added.

When asked about how living near a shipyard affects her psychologically, Rita*, speaking to us in her home in Cospicua, described a constant sense of unease about the air pollution generated by the shipyard’s industrial activity.

“Obviously, it’s not pleasant to spend your time worrying about these kinds of things. I have plenty of other things to worry about in my day-to-day life, this is an extra layer which I shouldn’t even have in the first place,” she says, echoing a sentiment expressed by more than a dozen interviewees from Senglea, Cospicua, and Vittoriosa.

Peter recounted how his 88-year-old father developed breathing difficulties over the past three years.

“My elderly father didn’t have breathing problems before. Now, he does. In the last three years, he’s been suffering from asthma. He has to take his inhaler every day and he often needs to go to hospital for treatment,” Peter said.

“I don’t know whether it’s because of his old age or because of the problems with air quality here. My father has been living in Senglea all his life,” he added.

While this may not be a narrative that is familiar to the average reader, for residents like Peter and Louis, these scenarios are a description of their day-to-day reality.

An MSC cruiseship berthed in Palumbo shipyard in 2021.

Formerly an integral part of the British Empire’s military presence in Malta, the dockyard, as it is commonly known, is now owned by Palumbo Shipyard and their business partners, MSC Cruises.

Palumbo Shipyard, which is a subsidiary of the Italian Palumbo Group SPA, was granted a 30-year concession agreement for the dockyard in Cospicua in 2010. In 2020, MSC Cruises SA, a global cruiseliner company headquartered in Switzerland, bought 50% of Palumbo group’s Malta-registered companies, effectively taking over partial ownership of the dockyard.

Rita, Peter, and Louis were among the residents who had cried foul when, in July 2020, press reports officially confirmed rumours that MSC Cruises and Palumbo Shipyard were about to strike a deal. Their concerns about increased pollution generated by the shipyard were later vindicated by the intensification of industrial activity that came about as a result of a deal that was not subject to public consultation.

ATAL had sent a public letter to the office of the prime minister and several members of Parliament in March of that same year.

Among other things, the letter appealed to authorities to engage with affected stakeholders, consult with them before any changes in the shipyard’s operations are implemented, and to follow up on reports of maladministration from the concessionaire, Palumbo Shipyard.

When residents had sent out their letter, just a few months before the deal was officially confirmed, Palumbo Shipyard had, according to a Times of Malta report, described the letter as “nothing but provocation from the usual suspects who, for the past 10 years, have been bent on seeing the destruction of the shipyard, little realising the harm they are causing not just to the facility on an international level, but also to Malta.”

Palumbo Shipyard does not publish any figures about the volume of ships which enter and exit the shipyard and it does not publish any data related to the emissions generated by its operations.

While this lack of information hampers the possibility of adequately assessing the situation on the ground, open-source data obtained from vesselfinder.com by our investigative partners Reflekt shows that the volume of different ship categories peaked in different years – passenger ships, along with cruise and cruise ferry ships, peaked in 2021, while cargo ships and tankers peaked in 2022.

In terms of the number of hours ships spent in the shipyard, the trends that can be observed when comparing 2021 to 2019 are as follows:

– a 590% increase for passenger ships with a gross tonnage above 50,000 tonnes,

– a 127.3% increase for cruise and cruise ferry ships, and

– a 91.4% increase for passenger ships.

While no ships with a gross tonnage above 100,000 tonnes were detected in 2019, they spent a total of 1,843 hours in the shipyard in 2020. That volume nearly doubled to 3,548 hours in 2021.

The 127.3% increase in the number of hours cruise and cruise ferry ships spent in the shipyard is particularly significant due to concerns about the particularly high levels of emissions emitted by cruise ships.

In a report published in January 2021, the European Network of Corporate Observatories (ENCO) noted that “cruise ships are renowned for producing enormous quantities of pollution, in the form of NOx, sulphur dioxide, particulates, sewage and of course huge quantities of carbon dioxide”, estimating “that one cruise ship emits as many air pollutants as five million cars going the same distance”.

The number of hours passenger ships, cruise, and cruise ferry ships spent in the shipyard declined in 2022:

– passenger ships with gross tonnage above 100,000 tonnes by 65%,

– passenger ships with gross tonnage above 50,000 tonnes by 45%,

– cruise and cruise ferry ships by 39.5%, and

– passenger ships by 19.3%.

As for cargo ships and tankers, the volume of hours spent in the shipyard peaked in 2022 for both vessel categories. In that year, the number of hours cargo ships spent in the shipyard increased by 62.2% when compared to 2019. The number of hours for tankers increased by 125%.

It is significant to note that the time period showing increased shipyard activity, following the joint venture, also coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw residents spending more time at home.

The implications

We discussed our findings In an exclusive interview with air quality expert Axel Friedrich. Axel, whose vast experience in the field draws on decades spent working at the German government’s federal environment agency and includes a principal role in uncovering the DieselGate scandal, recently visited Malta in August of this year as part of his research-based campaigning to tighten air quality regulations in Europe.

Dr Axel Friedrich

When asked about the immediate health impact on residents in the Southern Harbour region, the air quality expert singled out the proximity of the shipyard with residential areas as a uniquely aggravating characteristic among harbours in the Mediterranean.

“This shipyard is located in the middle of a city, which means a medium-sized enterprise sitting in the middle of a city, which is normally not the case. Normally, we separate these two activities, living and industrial activities,” Axel said during the interview.

One of the activists involved in ATAL is Josianne Micallef. She lives in Senglea. She describes her decision to move to the town two years ago as a lifelong dream come true.

Josianne, a resident in Isla who lives close to the shipyard.

“I always wanted to live in Senglea. Whenever I came here, it felt like I was going abroad,” she says when asked about what drew her to the town.

“Every day, I think about how lucky I feel to live in a place that’s so beautiful. The shipyard is the only problem that there really is here,” she adds, referring to the levels of air and noise pollution.

Josianne frankly points out that, while she was aware that the shipyard would be something she has to live with to move to her dream town, it is the overriding feeling that the company can operate unhindered by adequate monitoring and enforcement that gets to her. Josianne argues that ATAL’s campaign wishlist amounts to just that: fulfilment of their right to know about the impact of the shipyard’s operations and reassurance that the shipyard is bound by a set of regulations that is strictly enforced.

While Josianne’s exposure to the shipyard’s activities varies according to the level of industrial activity going on that particular day, her weariness of the long-term impact of exposure is constant. While the shipyard was relatively quiet on the day of the interview, she described how just four days before that, she “couldn’t even open up the balcony” because she couldn’t hear herself or her partner talking. That day, noises generated by hydroblasting went on from 8am to late in the night.

Asked to elaborate on why she thinks the activist group’s campaign is worth fighting for, Josianne puts it succinctly: “It’s important because there is nothing more important than the air we breathe everyday.”

A pillar of the community speaks up

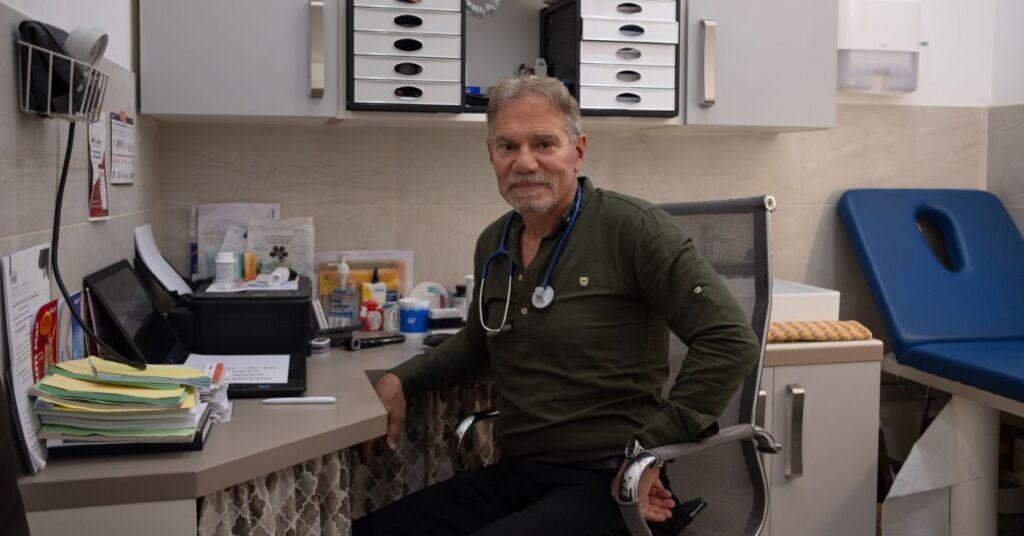

We first met Dr Joseph Tonna, a general practitioner who has been living and working in Senglea practically all his life, in his hometown’s Gardjola Gardens, a quaint, tiny green space which sits at the very tip of the mini-peninsula on which the locality was built. He sees his patients regularly at Milia’s pharmacy, a small private clinic on Senglea’s iconic Triq il-Vitorja.

Portrait of Dr Joseph Tonna in his clinic. Dr Tonna has been a family doctor in the area for decades, and has noticed an increase in asthma over the past few years.

“Back when I first became a doctor forty years ago, whenever I would prescribe oral bronchodilators like Salbutamol to my patients, it was almost a bit of a taboo. They would be taken aback, it was so rare,” Dr Tonna had explained.

“Along the years, especially over the last decade, respiratory issues in both children and adults have increased drastically. We write up bronchodilator prescriptions on a daily basis now. A lot of the illnesses we deal with are respiratory,” he added.

Respiratory illnesses which necessitate oral bronchodilator treatment, such as asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases (COPD), tend to occur at a higher rate when people are exposed to various types of pollutants like the ones generated by the industrial activity occurring in the shipyard as well as the combustion of heavy fuel oil from the ships’ engines.

In a documentary titled Black Trail published in April 2021, Faig Abbasov, shipping director for Transport & Environment (a Europe-based NGO advocating for clean transport) describes heavy fuel oil as “the dirtiest fuel imaginable”, a cheap by-product that is left over from the production of diesel and gas.

Exhaust from MSC Fantasia while docked in Palumbo Shipyard for repairs.

We filed a Freedom of Information (FOI) request with the health ministry to obtain data about the total number of oral bronchodilator units granted through the same ministry’s Pharmacy of Your Choice (POYC) department over the last five years, along with a breakdown of which pharmacy distributed which amount of units in any given year. We also obtained information about how much taxpayer money the government spent to subsidise oral bronchodilators which patients can obtain for free through the POYC system.

The POYC unit is responsible for the granting and entitlement of free medical products and services to patients who require medication for chronic illnesses. After an initial, spurious refusal to the request and a follow-up complaint, the health ministry eventually reversed its initial refusal and granted full access to the requested information.

For the purposes of this investigation, we analysed the distribution patterns of three commonly-prescribed types of oral bronchodilators: beclometasone (250MCG), budesonide (200MCG), and salbutamol (100MCG). We also obtained data for beclometasone (50MCG), budesonide (100MCG), and fluticasone (both 250MCG and 50MCG).

Since oral bronchodilators with higher dosages are used for more severe respiratory issues, we focused solely on the highest doses of the most frequently used oral bronchodilators. Fluticasone was the least prescribed oral bronchodilator out of the total of five different oral bronchodilator medicines we obtained data for, and was therefore excluded from the analysis.

On the nationwide front, the data clearly shows that people in the Southern Harbour region – which includes Cospicua, Senglea, Vittoriosa, and Valletta, whose unique skyline is regularly overshadowed by massive cruise liner ships that often dock there – were the largest user-base for all three different types of inhalers analysed during this investigation.

The period covered ranges from 2018 – 2021. While we did manage to obtain data for 2022, the latest available regional population demographics are from 2021, meaning the comparison could only be made up until 2021.

From 2018 – June 2023, the government spent a total of €5.5 million to subsidise patients’ access to oral bronchodilators through the POYC scheme.

Another FOI request filed during the course of this investigation clearly showed that in 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022, citizens of the Southern Harbour region were the biggest residential cohort of patients discharged from Mater Dei Hospital following an asthma diagnosis.

Additionally, the Southern Harbour region was the only region in Malta to have an even higher rate of asthma discharges post-COVID – where, furthermore, the diagnosis hit record numbers.

A Parliamentary question filed by Nationalist MP Albert Buttigieg in May of this year also shed some light on the number of COPD-related hospital admissions.

Since 2017, the only other district that experienced a higher rate of COPD-related hospital admissions than the Southern Harbour was the Northern Harbour district.

Dr Tonna reviewed our data, along with the open-source data obtained from Vessel Finder. According to his professional opinion, he described the data as a further confirmation of his previous suspicions about the existence of a link between the shipyard’s industrial activity and the subsequently poorer air quality in the surrounding areas.

While it cannot be claimed that the high rate of respiratory illnesses in the Southern Harbour region is entirely due to the shipyard’s activity alone, the fact that the shipyard is a key industrial activity hub situated just metres away from dense residential hotspots, all occurring within the context of the Grand Harbour’s busy, restrictive space, remains.

What does the official air monitoring data tell us?

One of the main issues flagged by ATAL was the frequency with which ERA’s air quality monitoring station in Senglea malfunctioned, preventing the activists from adequately being able to assess the levels of key air pollutants like nitrogen dioxide and ultrafine particles grouped under the category of PM2.5.

It took protracted public pressure and lobbying from residents in the Three Cities to move authorities to install the station in the first place. It was only put in place after the deal between Palumbo Shipyard and MSC Cruises was signed.

As part of our investigation, we filed an FOI request with ERA to obtain validated data sets collected from the air monitoring station in Senglea. Since the air monitoring station was only put to use three years ago, the data we obtained covers 2020 to 2022.

The Senglea station reports hourly readings of the levels of nitrogen dioxide, nitrogen monoxide, sulphur dioxide and carbon monoxide. It also reports daily readings for PM2.5 and PM10 particles.

During the period under review, the monitor was unable to detect at least one type of pollutant 18.4% of the total amount of time it’s been in use from July 2020 – December 2022.

Friedrich voiced doubts about the location of the mobile air monitoring station in Senglea and the length of time taken to validate data-sets from 2022.

According to the European Air Quality directive, ERA is required to set up monitoring stations in locations that are determined by two criteria: the location in which one expects to have the highest level of pollution in the area, ideally in a location which also has a high density of people living in it.

The station in Senglea is located just outside Gardjola Gardens, at a considerable distance away from both population and pollution hotspots.

When we asked Friedrich to share his insights about the findings related to asthma discharges from hospital and the rate of patients admitted to hospital because of a COPD-related diagnosis, the researcher argued that the data clearly shows that the level of air pollution monitoring needs to step up.

“There’s an urgent need for the government of Malta to not only measure the air pollution required by the Air Pollution Directive but also monitor the concentration of ultrafine particles, particle numbers, and of black carbon to demonstrate the concentrations and take action to reduce it,” Axel said, adding that the delays in efforts to improve monitoring and enforcement “cost lives and money”.

To understand whether this failure rate was consistent among all air monitoring stations run by ERA or whether the station in Senglea was an isolated case, we also obtained the same data-sets from the air quality monitoring station in Msida for the sake of comparison. The Msida station’s failure rate for the same time period is 1.05%, far lower than the 18.4% observed in Senglea.

In addition, the data-sets provided by ERA through our FOI request have a huge missing chunk of data that has not been validated. 61.1% of the data from the station in Senglea is inaccessible for the purpose of this analysis due to a lag in the validation process from ERA.

In other words, the data does not tell us what the levels of air pollutants were for the last six months of 2022, even though experts like Friedrich confirm that the process of data validation should not take more than a month to conclude. The extent and frequency of data blackouts make it exceptionally difficult to understand the full extent of the air pollution exposure in the area.

“Abandonment”

One of the activists involved in ATAL is Yana Mintoff. Her family, including her father, former prime minister Dom Mintoff, is widely known in Cottonera. Yana has been a steadfast anti-poverty activist in her hometown for the last decade.

She has often been at the front-facing end of the collective’s meetings with key authorities whose area of responsibility involves Palumbo Shipyard.

These are the Environment and Resources Agency (ERA), Malta Investment Management Company Ltd (MIMCOL), Infrastructure Malta (IM) and the office of the environment minister, Miriam Dalli.

“Every time we go (to these meetings), we spend an hour, an hour and a half asking the same questions and not getting any answers, or getting passed on to other authorities, or being told that nothing can be done because there is no legislation about certain types of pollution like noise,” Yana continued.

“There’s no sense of responsibility. It’s worse than evasive – it’s abandonment.”

Yana Mintoff, one of the activists who forms part of the coalition, in her office.

Four months before the deal between Palumbo Shipyard and MSC Cruises was signed, the government made sweeping promises to install shore-to-ship technology covering the Grand Harbour area, originally announcing the €50 million project in February 2020. This year, Infrastructure Malta announced the completion of one of the shore-to-ship electricity points, which is situated in Senglea’s Boiler Wharf.

Such technology allows docked vessels to make use of power supplied by the national grid. Without such technology, ships rely on their own engines as a source of power, and therefore emit higher levels of pollution.

While the north side of the Grand Harbour has now been fitted out with shore-to-ship technology, Infrastructure Malta stated that it is yet to begin this process for the south side of the Harbour. The electricity point in Boiler Wharf, a Transport Malta operated charging point which began operating as a permanent cruise liner docking point earlier this year, is the only charging point in the south side of the Harbour so far.

We sent questions to Infrastructure Malta about the latest progress updates on the shore-to-ship project. Specifically, we asked about whether the Boiler Wharf project is included in the €50 million EU-funded budget, whether the agency can confirm that this electricity point will be used to permanently accommodate cruise-liners, a detailed breakdown of how the funds are being used, and whether Palumbo Shipyard will also be furnished with charging points.

In the responses provided to our questions, the spokesperson confirmed that the Boiler Wharf investment falls under the €50 million budget. The spokesperson did not provide a breakdown of expenses and was non-committal about whether Palumbo Shipyard will also be required to install charging points.

“After completion of the current ongoing project focusing on the north side of the Harbour, Infrastructure Malta has plans to implement more on-shore power supply investment targeting the south side of the Harbour, offering such facilities also to private operators like Palumbo,” the spokesperson said.

Short-sightedness

Josianne’s concerns about how the communities in Senglea are influenced by sponsorship money from Palumbo Shipyard were not just her own.

Tonna, along with all the other residents we interviewed throughout the course of this investigation, referred to the strong influence Palumbo Shipyard has over the communities in the Three Cities through sponsorships dished out to key entities like local councils, Senglea’s parish church, Senglea’s local band club, Senglea’s regatta club, and even the town’s football team.

Tonna, a proud Senglea native himself, is intimately familiar with the dynamics generated by this sponsored influence.

“Because of that influence, everyone keeps their mouth shut,” Tonna said. Tonna also remarked that he sustained criticism from prominent community interests who received sponsorships from Palumbo Shipyard whenever he spoke about the health impact of air pollution in their hometown.

“I always tell people the same thing: that decision is a short-sighted one. This year, Senglea’s football club got a promotion. There was a lot of joy in the community. We won the Regatta shield as well. This brings a sense of camaraderie, so the community doesn’t want to lose that sponsorship. It’s difficult to find people who are willing to speak up (about air pollution) after something like that happens,” he added.

We tracked down a total of eight community-led initiatives and organisations in the Three Cities which received sponsorships from Palumbo Shipyard. We asked these entities to explain whether they saw any issue with speaking up about air pollution generated by one of their main sponsors and whether this amounted to a conflict of interest with their stated aim of representing their community’s interests.

We sent these questions to all of the below, but received no replies.

This is one half of the first article in an investigative series titled ‘Particulate Matters’.

Reporting by Julian Delia, Joanna Demarco, Christian Zeier, and Anina Ritscher.

This investigation was funded by journalismfund.eu through its environmental reporting grant.

Further funding was obtained from the Citizens’ Lab Fund as administered through SOS Malta.

All photos by Joanna Demarco

What do you make of these revelations? Sound off in the comments below and read what the authorities had to say about the investigation here.