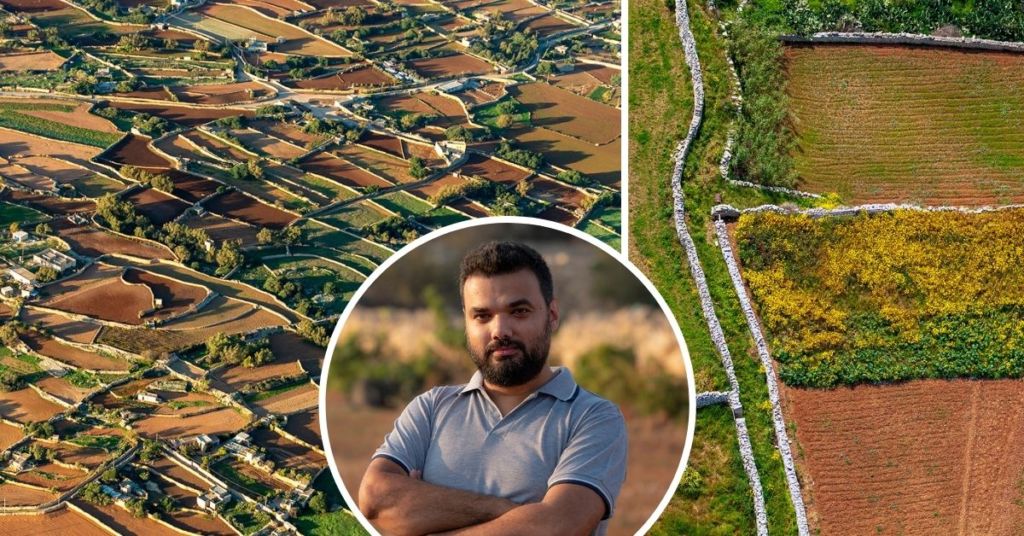

Saving Farmland Requires Sweeping Regulatory And Policy Change By Maltese Government

Malcolm Borg of the NGO Ghaqda Bdiewa Attivi went to court this week in a bid to save Malta’s rural landscape as we know it.

“Farmers are facing their greatest problem ever,” Borg told Lovin Malta. “This can really bring down the agricultural sector.”

Borg is the coordinator of the NGO, which is funding the court appeal against an eviction order served on two 72-year-old farmers who have tilled fields in Żabbar on leasehold for decades.

The eviction is the first of its kind, serving as a precedent that is expected to spawn many such cases. There are already 40 similar cases working their way through the courts. Other farmers have been receiving lawyer’s letters demanding exorbitant raises in ground rent.

These legal contestations – as well as the appeal – arise from the lack of proportionality between ground rent and price of land. Constitutional courts tend to accept restrictions on private property rights in the public interest – such as protecting the environment or agricultural land – for as long as such proportionality is maintained.

Credit: Daniel Cilia

Lovin Malta has published a separate analysis on the eviction order and appeal.

Yet resolving proportionality would not save farmland unless the runaway price of land is reined.

“The court expert evaluated the price of the fields using a measure to calculate the price of commercial land,” Borg said, referring to the case in Żabbar, in which the court expert set the price for the fields and agricultural store at €845,000.

“If the rent has to be a proportionality of the price of land, the price of agricultural land has to remain low. Farmers can never afford to pay a rent that is a percentage of the commercial price of land.”

Lovin Malta has seen legal letters being sent to farmers in which landowners are demanding raises of ground rent amounting to several thousand annually.

This may be proportional to the price of land – if rent had to be equivalent to a couple of percentage points – but it would be an extra cost that would cascade to higher vegetable prices and all farm produce, including dairy (much land under lease is used to grow fodder for dairy cattle).

“That is not an option for farmers,” Borg said, “because consumers would buy imported vegetables or products instead and a farmer would not be able to compete.”

Malcom Borg - Credit: Daniel Cilia

The price of land in the countryside has been rising rapidly in the past few years on the back of speculative investment that is in turn driven by greater ease of acquiring development permits outside the development zone as well as rising demand for recreational plots in the countryside.

Planning policies of the so-called Rural Policy and Design Guidance, issued in 2015, made it easier to get development permits beyond development zones. It became possible to get permits for stables and to have rooms and defunct farms to be redeveloped into dwellings.

It also allowed swimming pools to fully spill over-development zones, and developments at the edges of development zones have also been allowed to protrude into Outside Development Zones. All of this has allowed development to proliferate in the countryside, and speculatively drive up the price of land in the countryside.

Fields sold for recreation now cost tens of thousands, rising to hundreds of thousands in the case of fields adjacent to a road or having a room and a view.

Borg said: “Morally and ethically, there is nothing wrong with people who want to have a field to enjoy the countryside. After all, there are people who have no garden and no roof. But it has increased demand for land, and hence driven up prices. Buying a field is also seen as an asset, as an investment.”

Credit: Daniel Cilia

A resolution of the European Parliament passed a few years ago warned about “non-farmers increasingly interested in purchasing agricultural plots, very often for purely speculative purposes.”

It then called on Member States to discourage or avert “speculative land transactions” on agricultural land. It also called on governments “to give small and medium-sized local producers, new entrants and young farmers priority in the purchase and rental of farmland.”

Borg, whose NGO represents commercial farmers, says that the demand for recreational plots in the countryside has intensified with the advent of COVID.

“It’s the government that has to find a formula to resolve this problem,” Borg elaborated. “The starting point has to be that the use of agricultural land has to remain exclusively for agriculture, and the ground rent has to be at a level that encourages agriculture use and not any other uses. Agricultural land is of fundamental importance to the country.”

Borg believes that the fact that Malta is 80% reliant on food imports makes protecting agricultural land for agricultural uses more compelling.

“We are an island State in an unstable geographical region and we rely on other countries for our food,” he said. “That puts us in a vulnerable situation. For example, when COVID broke out, some countries initially started hoarding food produce. So, it makes sense that as a country we maintain some agricultural production in order to have a buffer, or resilience, in case of any external shocks to the food supply.”

Cover photo credit: Daniel Cilia

What do you think about this issue?