When The Sea Plays Into A Mini-Tsunami: A Deep Dive Into Malta’s ‘Milgħuba’

The following is an explainer into Malta’s seiches or “milgħuba” by Aldo Drago, Professor in Oceanography at the Malta College of Arts, Science & Technology.

He set up the Physical Oceanography Unit and has led several research projects over several years, setting the foundations for real-time meteo-marine observations and forecasting in the Maltese Islands. Among his research activities, he initiated and continued to conduct sea level measurements since 1993, with installations at various coastal stations in Mellieha Bay, Portomaso, Marsaxlokk and the Grand Harbour.

The Milgħuba is a known phenomenon which has been studied and about which we have already written a lot. Yet when it happens it raises fascination and curiosity by the people who experience it. The low-lying streets near the coast such as in particular areas in Marsaxlokk, and near the Worker’s Monument in Msida, become flooded when there is no rain and the weather is perfectly fine. The sea comes in and retreats over several repeated cycles, each a couple of tens of minutes long.

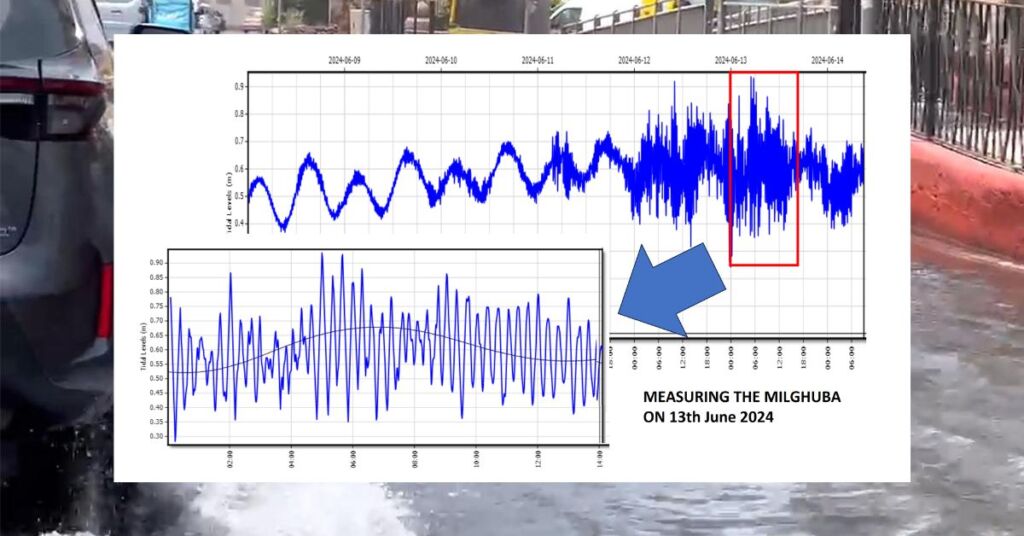

This is the Milghuba which was experienced again last Friday, especially in the early morning hours. The phenomenon was monitored by a Transport Malta sea level station in Marsaxlokk. The zoomed frame in the picture is a sea level record of the phenomenon, with excursions of the sea surface going up and down following vertical excursions of more than 60cm, and reaching peak levels at 5 and 5.30 am GMT (7am and 7.30am local time).

The longer track of sea level recordings at the top of the picture shows how the seiches started much earlier (from 12th June onwards), but the sea level became more prominently high when the tide (black line) was also at its rising phase. Indeed, the seiches are very common in our sea, but when a combination of factors add up, they then become more evident.

Observations made by sea level gauge operated by Transport Malta in Marsaxlokk

The Milgħuba has long been observed and studied, but its real trigger and source was explained only in the late 1990s through the work of scientists studying the phenomenon in the Balearic Islands as well as in the Maltese Islands by the then Physical Oceanography Unit, led by the author of this article

Our fishers are well acquainted to the phenomenon. In fact, the Maltese name for these seiches comes from the verb ‘lagħab’ and ‘milgħuba’ translated in English means ‘play of the sea’. The oldest records of these seiches go back to 1860 when Sir Airy studied tidal records measured by a mechanical sea level gauge by the British Admiralty in the Grand Harbour.

The origin of these seiches is now known. They are triggered by atmospheric gravity waves which propagate on density interfaces in the air, and favoured by particular atmospheric conditions often related to upper air flows from the SE. For this reason, seiches often occur in coincidence with dust loading in the atmosphere drawn from the Saharian desert.

Seiches are not created directly in the ports or embayments, but originate in the open sea, moving towards land like a mini-tsunami.

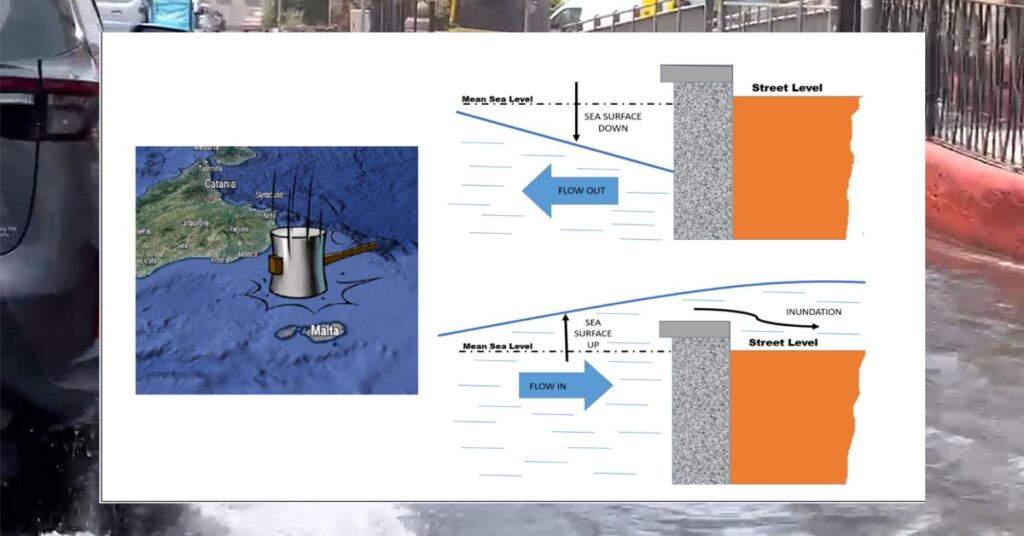

Graphic showing how the sea in the first phase of a seiche cycle retreats outwards as the water level drops, while in the later phases it fills inwards towards the coast, overcomes the embankment and overflows on land. This cycle can repeat several times.

The air waves in the atmosphere are the trigger. As they propagate in the atmosphere, they create a varying pressure on the sea that we can compare to a big hammer hitting the surface of the water. This brings with it a series of ripples in the sea, somewhat different from the normal waves that we usually associate with the impact of the local wind, basically because they have much longer periods of the order of minutes. In the open sea these waves extend over a range (wavelength) of tens of kilometres.

In the open sea this wave is only a few centimetres high. When it reaches the beaches the length of this wave gets shorter and the resonance with the mass of water in the beach area makes the wave get stronger and reach its highest point on the inner coast of the beaches where the water level can go down and up, by more than a metre in a few minutes.

During the flooding phase the water follows a tsunami-like behaviour and in a few minutes it first retreats out of the shore with the consequence that the water is lowered, and where the sea is shallow the land is exposed; after that, the water comes back in full force and rises far above the normal level so that it floods the land near the coast. Therefore, this phenomenon is very similar to a tsunami, but it is in no way linked to seismic activity or earthquakes. Following the atmospheric origin, it is often called a meteo-tsunami.

Have you ever experienced a seiche? Send this to someone who’d love to find out more about this natural phenomenon

Lovin Malta is open to interesting, compelling guest posts from third parties. These opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the views of the company. Submit your piece at [email protected]