Guest Post: Naxxar Lions Are A Symptom Of A Much Bigger Problem

Last December’s discovery of lions and a panther being kept in sub-standard conditions in Naxxar has shocked many—but for those of us working in the field of animal welfare, this case, while alarming, is sadly just the tip of the iceberg.

The truth is, we have long known that dangerous animals are being kept in residences and other environments that are completely inadequate for their physical and psychological wellbeing. What we do not know, however, is the true extent of the problem.

Born in Captivity Is Not Born for Captivity

Let me be clear: I am, and have always been, unequivocally against the keeping of wild and dangerous animals in captivity.

Whether they were born in the wild or in captivity, lions, tigers, primates, venomous reptiles, and other such animals are not suited to human environments.

Even when provided with food, veterinary care, and affection, these animals are deprived of their most basic natural instincts—roaming vast territories, socialising with their species, hunting, climbing, and living in complex, ever-changing ecosystems.

A lion born in captivity still needs space to roam and a pride to interact with. A monkey kept as a pet will never thrive without the mental stimulation and social dynamics of a troop. A snake needs climate regulation and space to behave naturally, not a terrarium in someone’s living room.

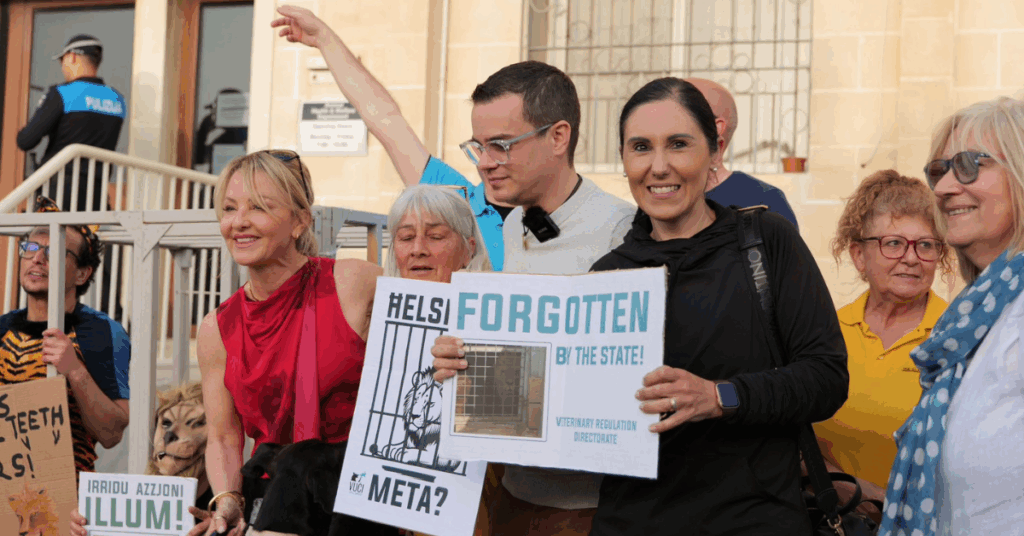

Which brings me to a question that has been circulating: Why wasn’t I, as Commissioner for Animal Welfare, present at the recent protest organised by activists?

I deeply respect and often agree with the causes championed by animal welfare activists.

However, the role of the Commissioner is governed by legal and ethical standards that demand neutrality and impartiality.

My duties include enforcing animal welfare laws, making policy recommendations, and working collaboratively with all relevant stakeholders—including government entities.

While nothing in the law explicitly prohibits me from attending such protests, doing so could compromise the perceived objectivity and effectiveness of my office.

Although my actions may not always be visible to the public and even in this non-executive position, I am always pushing, raising my voice, and fighting with every tool available to ensure that these animals—and others in similar situations—get the best outcome possible.

Now that we can’t give them back the life they were meant to have, we need to keep trying to give them a better future.

The Amnesty – A Step Toward Truth

The recently announced amnesty aims to shed light on a situation that has long remained hidden.

It gives owners the chance to voluntarily register any dangerous animals they currently have, without facing legal penalties.

While we know this measure won’t uncover every case, it will help us build a more accurate picture of the scale of the problem.

Without the amnesty, we would have remained at a status quo, only discovering the presence of such animals when it’s too late or when a tragedy occurs, such as if they escape. Since it is not feasible nor legal to check door-to-door in every residence, this amnesty, while not ideal, is the better option compared to doing nothing.

We Must Do Better

As Commissioner for Animal Welfare my priority will always be justice for animals.

When a country like Malta does not have the space, the facilities, or the trained professionals to provide even a basic safety net for dangerous or exotic animals, those animals simply should not be allowed here. Full stop.

It doesn’t matter how well-meaning an owner claims to be—because good intentions do not build sanctuaries, replicate natural habitats, or undo a lifetime of suffering behind bars.

Time To Draw the Line

Keeping wild animals for show, status, or fascination—no matter how much affection or care an owner may believe they are providing—results in suffering, even if that suffering is unintended.

Intent does not erase impact. The truth is, wild animals have complex physical, social, and psychological needs that no private setting can ever truly meet. While some owners may act out of ignorance rather than malice, the state has a responsibility to know better.

By allowing this to continue, we are not just condoning the suffering—we are enabling it. Malta must draw a clear and uncompromising line: we cannot provide the right environment for these animals, then they should not be here, simples!

So, What Now?

As Commissioner for Animal Welfare, my role is a consultative one — this means that while I can make formal recommendations to the Government, I do not have the executive authority to implement them myself.

Unfortunately, this distinction is often misunderstood by the public, which has led to undue criticism, and, at times, abuse directed at both myself personally, and my office.

In the case of the lions found in Naxxar, I recommended that the animals be confiscated, relocated abroad to a suitable sanctuary, and that the owner be charged in accordance with the law.

My understanding is that these recommendations are being followed, but—as is often the case—legal and procedural complexities are causing delays (four months and counting).

While thoroughness and legality cannot be rushed, especially in sensitive cases involving living beings and public safety, we must not forget that animals are suffering every single day these decisions are delayed.

As Commissioner, this is what I urge people to keep in mind and act upon — especially before ever supporting the idea of bringing or keeping wild animals as pets.

Alison Bezzina is the Commissioner for Animal Welfare