Maltese Modern Art and Identity – Some Considerations On The Debate

The historically very recent debate on Malta’s collective memory and identity – collective identity being a term that emerged in 1960s global contemporary historical discourse as noted historian Eric Hobsbawm shows – is one which, like all identity debates, presents contradictions and political nuances according to ideological positions.

In modern history, this debate was central to political fora with the Strickland-Mizzi dispute on whether Maltese roots were either Phoenician or Latin, hence Anglo-Saxon or Italian, a debate which showed how politically polarized the question of identity can be.

Since the post-war years, the discussion has focused on defining Malta as an independent nation, spearheaded in the political arena by Borg Olivier and Mintoff with the strive for socio-economic autonomy. The study of Maltese art and its history has naturally engaged with the evolution of the identity debate and art’s conveyance of selfhood as a collective notion.

Through his publications, lectures, as well as informal conversations, Prof. Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci (Professor of modern and contemporary art history) from the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Malta, is tackling the many issues presented by the identity debate within the sphere of modern art, together with my own research assistance and conversations with colleagues and students.

This continuous exchange has highlighted certain characteristics which, thanks to the invitation of Te fit-Tazza and Lovin Malta, are being addressed here to raise awareness on arguments currently being debated:

In the field of research and curatorship, there is a tendency to show how foreign artists and movements have influenced Maltese modern art without considering how the Maltese themselves developed aesthetic experimentations alongside their contemporaries and, in some cases, even left an imprint on the work of their overseas counterpart. This can be encountered in academia and at the state level, as well across more popular platforms, albeit the many positive changes.

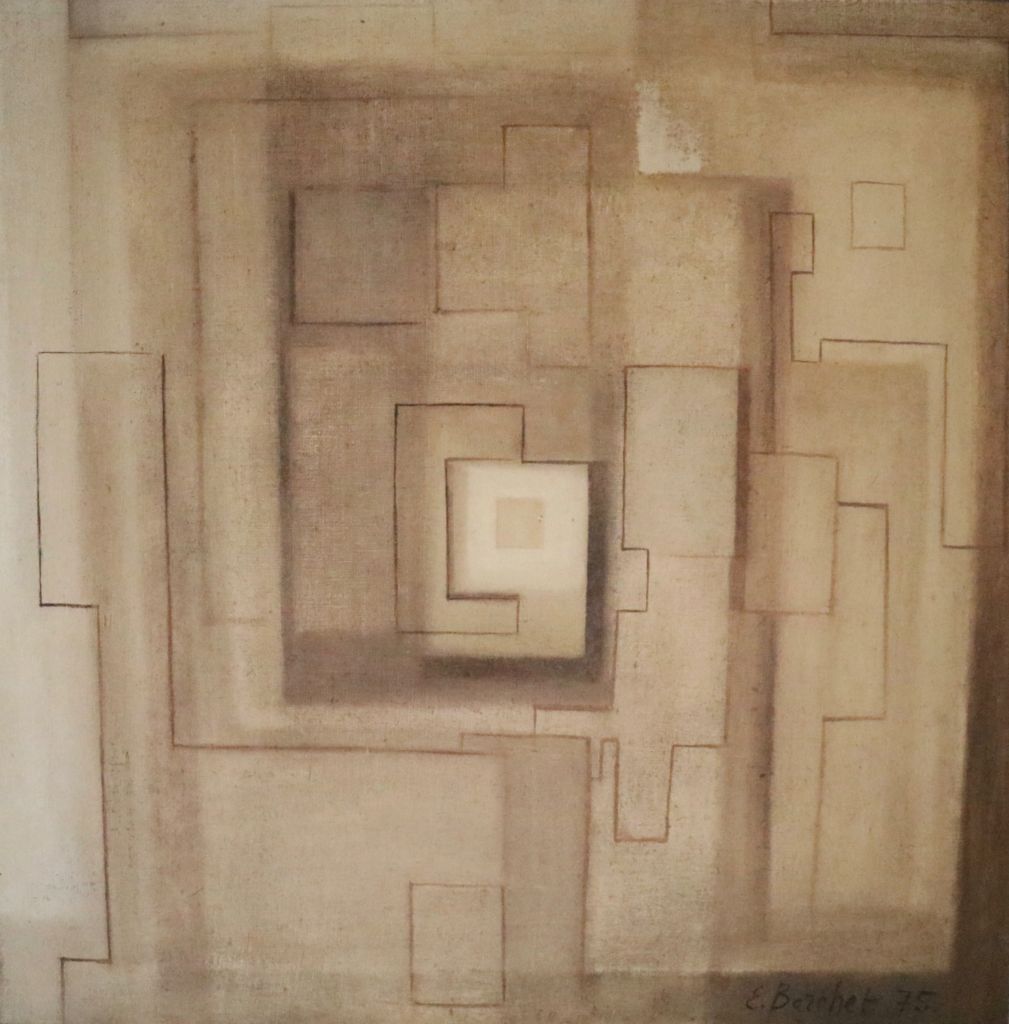

Esprit Barthet, Abstract, 1975. Photo credit: Emma Micallef. Image courtesy: APS Mdina Cathedral Contemporary Art Biennale

Notwithstanding, the term ‘foreign influence’ is not without discrimination. Oftentimes, the dialogue with foreign modern artists and movements seems to be exclusively European or Western. This means that the position of Malta as forming part of Southern Europe is upheld as the leading narrative, rather than that of Malta as the nucleus of the Mediterranean – a region that bridges Europe with North Africa, East and West, together with various languages, religions, and artistic traditions. The links with the Mediterranean region are now being addressed in research, and by several established contemporary Maltese artists.

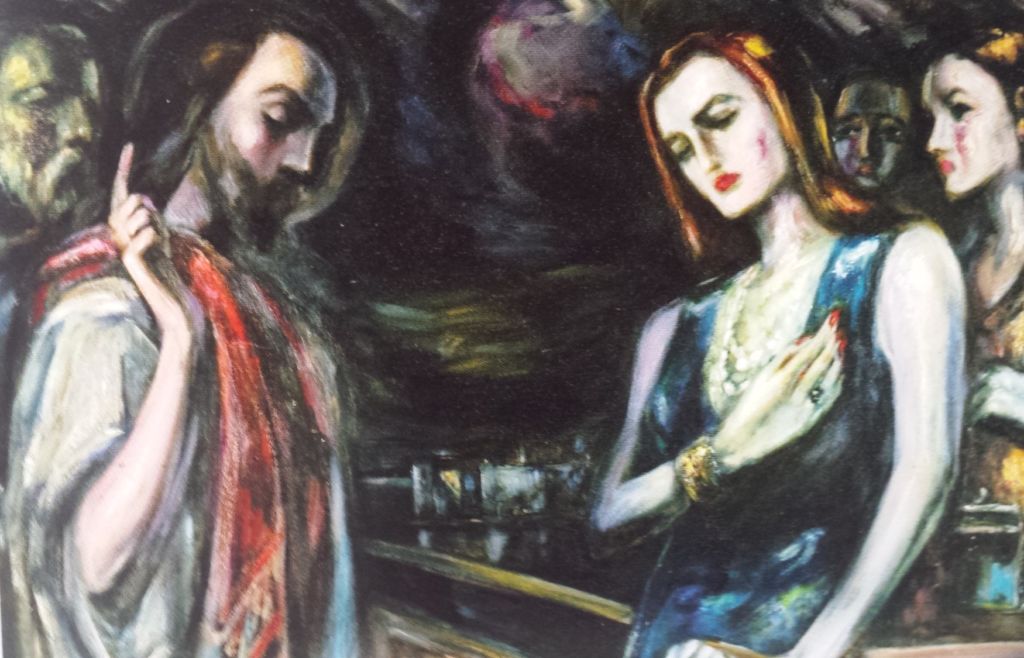

Carmelo Mangion, Christ and the Adulteress, undated. Photo credit: Peter Bartolo Parnis. Image courtesy: Carmelo Mangion family archives

One issue, speaking on a more general level, is that knowledge on famous artworks located at a geographical, and often even cultural, distance sometimes supersedes that of artworks and found metres away from our very homes. The names Josef Kalleya, Carmelo Mangion, Giorgio Preca, and several others, are seemingly absent from the collective consciousness, as are public artworks visible to all. This means that our modern artists and artworks exist on the margins of collective memory in spite of their significance to understanding the evolution of our cultural identity.

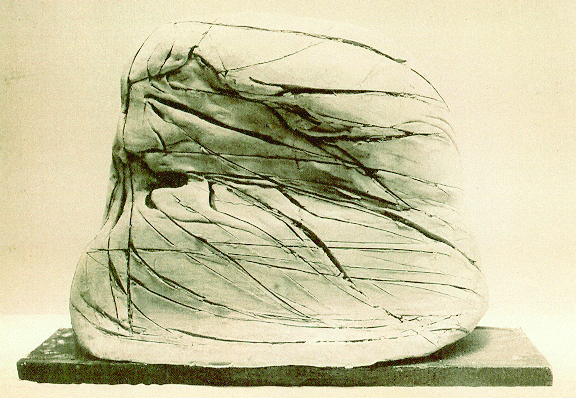

Toni Pace, Sea Urchins, 1965. Photo credit: Elisa von Brockdorff. Image courtesy: APS Mdina Cathedral Contemporary Art Biennale

One argument presented by Schembri Bonaci is a development on J.J. Cremona’s statement about the characterlessness of Maltese art. This was presented by Cremona as a defining quality in itself, and has been appropriated by Schembri Bonaci to argue for the hybridity and eclecticism of Maltese modern art – “the lack of uniformity and ideological-aesthetic consistency in the arts” as Schembri Bonaci puts it – encapsulating the plurality of Malta’s modern art.

Josef Kalleya, Enigma, 1970. Image courtesy: Josef Kalleya family archives

Finally, the subject of the public dialogue surrounding and influencing the development of art in twentieth-century Malta is one that reveals an apparent lack of critical engagement with the aesthetic choices made by artists, as well as with the politics of such choices. As the century progressed, dialogue gradually opened up beyond the limits of reportage and descriptive text. Thankfully, great strides have been made to address the arts with critical viewpoints, and committed writings on Maltese modern and contemporary art have been published in relatively recent years.

Josef Kalleya and Victor Pasmore at Kalleya's Blata l-Bajda studio in the early 1970s. Image courtesy: Josef Kalleya family archives

From my own sphere of academia and curatorship, and thanks to the many projects headed by Schembri Bonaci, these points and others serve as guides for the development a theoretical and historiographical path for the study of Maltese modern art, to work towards establishing an objective and critical debate across research and creative platforms.

Nikki Petroni read for an undergraduate degree in History of Art at the University of

Malta and pursued postgraduate studies at University College London (UCL), graduating in 2013. She completed a Ph.D. in Maltese Modern art at the University of Malta in 2019 under the supervision of Prof. Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci. She is a visiting lecturer in Modern and Contemporary art at the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Malta. Petroni is part of the curatorial committee of the APS Mdina Cathedral Contemporary Art Biennale and Coordinator of the Strada Stretta Concept (Valletta Cultural Agency). Aside from being an independent researcher and curator, she has edited several academic essays, books, and exhibition catalogues.

Lovin Malta is open to external contributions that are well written and thought-provoking. If you would like your commentary to be featured as a guest post, please write to [email protected], add Guest Post in the subject line and attach a profile photo for us to use near your byline.

Do you agree?