Trials By Jury Shouldn’t Serve As An Excuse For Stifling Free Expression In Malta

The court ban on the airing of a televised interview with Miriam Chetcuti, whose daughter Chantelle was murdered by her estranged partner two years ago, is another reminder of the need for reforms of the judicial process, particularly the trial by jury system.

On Thursday, the Criminal Court accepted an urgent request to ban the interview, which was due to air during an episode of ONE TV’s discussion programme Awla on murders. The application was filed by Justin Borg, the accused in Chantelle Chetcuti’s murder case, who is expected to face a trial by jury.

He asked the court to ban the programme’s producers from showing the interview, discussing or referring to the case in any way, on the grounds that it would prejudice his right to a fair hearing.

Borg argued that Awla’s large viewership meant the interview and any subsequent discussions about the case could be viewed by potential jurors, who could be influenced against him by it.

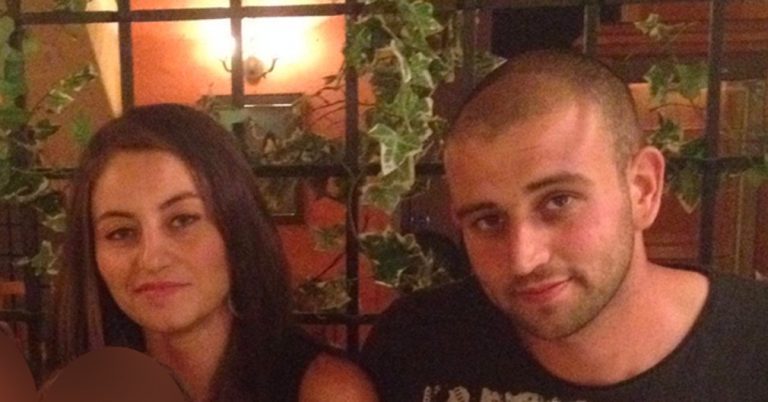

Chantelle Chetcuti with her former husband Justin Borg

A similar argument was made by former police officer Simon Schembri, who in 2018 also petitioned the courts to ban a Xarabank interview with Liam Debono, the man charged with his attempted murder.

In Schembri’s case, the Court of Magistrates had accepted to ban the interview on the basis of a legal provision allowing the judiciary to prohibit the publication of material related to a case until before the end of proceedings.

Borg’s request – filed a few hours before the programme was due to air after he was alerted to it by a promotional video online – was accepted provisionally and a sitting appointed next week for the court to hear both sides’ arguments.

This means that on Wednesday, a judge could still overturn the decision to ban the interview. However, the case does bring to mind a warning by the editors of the country’s four leading independent media organisations following the Schembri case in 2018.

The decree, they had said, risked “opening the floodgates for similar decisions” that would place the press in contempt of court by reporting about an ongoing criminal case.

“We feel this is unprecedented in the recent history of journalism. The decree punishes journalistic endeavour that can create offence – something safeguarded by the European Court of Human Rights,” they said.

The two cases are similar, but they are also different, in that while Borg is the accused in this case, Schembri was the victim in his.

Both, however, justified their request on similar grounds: that this one interview in the constant stream of content we receive every single minute on our multiple devices – would be the one to give the other party an unfair advantage and elicit public sympathy.

It is true that the influence of press coverage on a story, situation or court case – especially when strategic and sustained – cannot and should not be downplayed. It is also true that not all stories are created equal.

However, at this stage, I believe we should be questioning whether it is still feasible for our legal system to be based on the assumption that people are somehow naturally independent or impartial.

The way we consume information today is barely recognizable from the way we did ten years ago, let alone when the laws of criminal procedure were drafted.

We live in the age of social media bubbles, and the average person will consume a vast amount of personalised, targeted information every day. While is easier to broadcast a message today, it is also a lot more difficult to cut through the noise.

Malta is also a country barely the size of a small European city – where any major event is reported upon instantly and reaches practically everyone that isn’t asleep within minutes – and which then dominates media reports, politicians’ statements, and everyone and his dog’s thoughtful Facebook post for days if not weeks after.

Can we really assume, and indeed count on, jurors to come into a trial without any preconceptions, and can we be banning publications in order to preserve their supposed impartiality?

A demonstration that was held the day after Chantelle's killing (Photo: Women's Rights Foundation/Facebook)

Arbitrarily wielding the power of the courts in what should essentially be editorial decisions – with the understanding that these are taken maturely and responsibly – is dangerous because it creates another avenue for stifling journalistic expression, without any trade-off.

Chetcuti’s case elicited national outrage which saw demonstrations in the streets. The criminal proceedings have also been covered extensively.

It would require a huge suspension of belief to assume that none of the jurors that will be deciding Borg’s fate will go into the trial without any preconceived ideas about the case. And if we can assume they weren’t unduly influenced by the coverage that immediately followed the murder, why should we assume they will be now?

If anything, the news that an interview was banned by the courts will likely garner more attention than the interview would have in the first place, and gives the impression that the one side in the case is being victimised by the system. What is there to be said about how that could influence a juror, I wonder?

Maybe it is time to do away with the trial by jury system altogether, particularly because of how small Malta is and how inevitably connected to each other we all are, in some way or another. With criminal cases becoming more and more complex, society would likely be better suited to having panels of qualified and accountable adjudicators decide.

Share this with someone that needs to read it