Meet This Year’s Winner Of Europe’s Highest Award For Human Rights Fighters

Fighting your fears and struggling to change that one trait about yourself that some might find annoying and problematic becomes the talk of the day this time of the year. But for some people, this internal battle takes on a much larger, much more selfless nature throughout their lives… and this time of the year, we look back and remember their valiant efforts far from our own tiny Mediterranean shores.

This Wednesday, the European Parliament in Strasbourg will be giving out the annual Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought – a high honour that comes in the shape of a certificate and €50,000 – to one Ilham Tohti.

But who is Ilham Tohti, and why does Tohti deserve to take home such a prestigious honour?

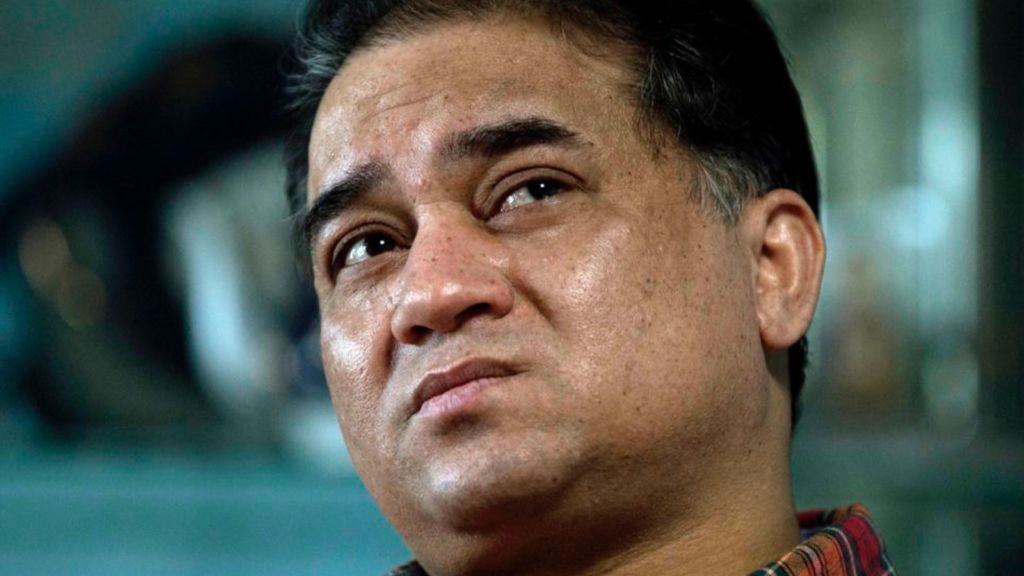

Ilham Tohti

lham Tohti is a renowned Uyghur human rights defender, economics professor and advocate of the rights of China’s Uyghur minority.

A group of Turkic-speaking Muslims from the Central Asian region, the Uyghurs are one of a number of persecuted Muslim minorities in China, with the largest population living in the northwestern autonomous Xinjiang region.

Amidst horrific allegations and first-hand accounts of torture and forced political re-education under the threat of violence, the Uyghurs have been the victims of this conflict since as far back as 1931. More recently, however, the plight of the ethnic minority has been kicked into overdrive, and the world is definitely watching.

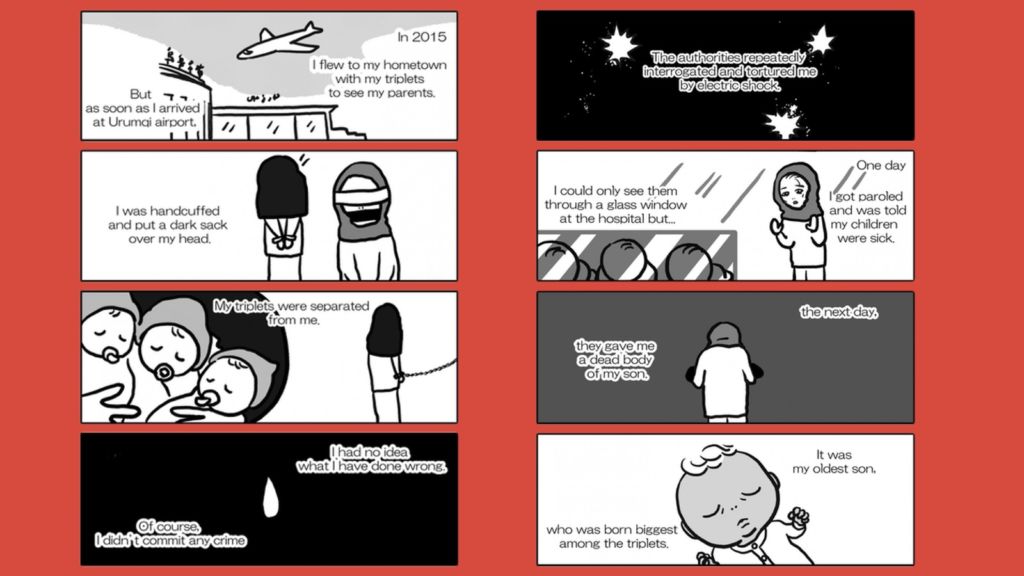

Just last weekend, Manchester City’s Turkish-German midfielder Mesut Özil took to social media to raise awareness on Uyghur persecution, leading Chinese state media to pull all of its TV coverage of the upcoming Arsenal-City game after he showed his support to the Uyghurs. Meanwhile, a Japanese comic book telling the tragic tale of a 29-year-old Uyghur woman from China is going viral online, already being viewed over a quarter of a million times in mere days and drawing millions of people to the region’s horrific tale.

Then came the concentration camps.

In recent years, a number of camps in Xinjiang started arbitrarily detaining Uyghur Muslims, forcing them to renounce their ethnic identity and religious beliefs and swear loyalty to the Chinese government.

Since April 2017, over one million innocent Uyghurs have been kept in this network of detention camps.

Excerpts from 'What has happened to me — A testimony of a Uyghur woman', a poignant manga by Tomomi Shimizu

Police at a protest by Uyghurs in China's Xinjiang region in 2016. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It is in this delicate and dangerous atmosphere that Ilham Tohti came to prominence.

For over two decades, economist Tohti has worked tirelessly to foster dialogue and understanding between Uyghurs and other Chinese people. However, his efforts for peace and increased human rights have merely landed him in a heap of trouble with authorities.

In September 2014, Tohti was sentenced to life in prison for his activism (branded as a separatist) following a two-day show trial.

In spite of all that he’s suffered, Tohti remains a voice of moderation and reconciliation. The suppression of his non-violent dissidence by an authoritarian state echoes Andrei Sakharov’s own woes 31 years ago, with the human rights concern in China now becoming a crucial international issue.

“This could help my father be away from potential harm from the Chinese government,” Ilham’s daughter Jewher said in reaction to this year’s award announcement earlier this year. “He was one of the very few people who could speak up for the Uyghurs, and it was very difficult for him to continue his work for so many years, even if he knew his work could get him into trouble… and prison.”

The last time Jewher Tohti saw her father was nearly seven years ago, in February 2013. The last time his family members heard about him was 2017… around the same time the first notorious camps started showing up.

Extending its recognition of the battle for human rights beyond the EU’s borders, the European Parliament will be recognising Tohti – and the Uyghurs’ plight – in a ceremony today, Wednesday 18th December. You can stream the ceremony live later today by clicking here.

The European Parliament has earned a reputation as a dedicated sponsor of people’s basic rights and of democracy. Fundamental rights apply to all people in the EU, no matter their status or origin. In fact, some of these freedoms are as old as Europe: life, liberty, thought, and expression.

Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani campaigner for children’s education, Yazidi women who had been prisoners of the Islamic State in Iraq, a doctor from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, political prisoners from Latin America: all have found a voice on the European Parliament’s stage.

This week’s ceremony has been months in the making, with the initial process of this year’s Sakharov Prize officially kicking off last September

It is around this time that, each year, MEPs nominate candidates for the prize. Each nominee must have the support of at least 40 MEPs (out of the 751), and each individual Member may support only one nominee.

After rigorous selection procedures involving joint meetings of a number of committees, a shortlist of three candidates is drawn up and then submitted to the Conference of Presidents for a final vote. The winner is usually announced in October (this year it was on the 24th), and the award ceremony takes place in December at plenary sitting in Strasbourg.

Shortlisted alongside Tohti this year were murdered Brazilian political activist and human rights defender Marielle Franco, Native Brazilian leader and environmentalist Chief Raoni, environmentalist and human rights defender Claudelice Silva dos Santos, and The Restorers, a group of five students from Kenya – Stacy Owino, Cynthia Otieno, Purity Achieng, Mascrine Atieno and Ivy Akinyi – who developed i-Cut, an app to help girls deal with female genital mutilation.

Last year, the Sakharov Prize was given to Oleg Sentsov, a Ukrainian film director who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for “plotting terrorist acts” against the Russian “de facto” rule in Crimea.

To really appreciate the Sakharov Prize’s worth in today’s society, we need to go back to the award’s namesake and its formation in 1988.

In a very different and turbulent world that was plunged deep into a Cold War, Russian physicist Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov had first come to prominence a couple of decades before as the father of the Soviet two-stage hydrogen bomb in 1955.

Growing increasingly terrified of what implications his invention had for the future of mankind, Sakharov spent the rest of his life raising awareness of the dangers of the nuclear arms race. By 1963, his efforts led to the signing of the nuclear test ban treaty. By 1970, he founded a committee to defend human rights and victims of political trials, and in 1975, he won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Back in the USSR, however, Sakharov was anything but adored by the powers that be.

Seen as a subverise dissident, Sakharov – fast approaching his 60s – was exiled to Gorky by Soviet authorities after becoming one of the regime’s most courageous critics, embodying the crusade against the denial of fundamental rights. He even actively fought for the release of fellow political dissidents in his country.

While in exile, Andrei Sakharov learnt that the European Parliament intended to create a prize for freedom of thought which would bear his name. From his exile, he sent a message to the European Parliament in 1987, giving his permission for his name to be given to the prize and saying how moved he was. He rightly saw the prize as an encouragement to all those who, like him, had committed themselves to championing human rights.

Andrei Sakharov

In 1988, the Sakharov Prize was born, with Nelson Mandela and Anatoli Marchenko being its first winners. One year later, 68-year-old Andrei Sakharov died on the eve of an important speech he was to deliver in Congress.

The prize that bears Sakharov’s name to this day goes far beyond borders, even those of oppressive regimes, to reward human rights activists and dissidents all over the world.

Since 1988, 36 exceptional individuals and organisations have been awarded the Sakharov Prize for their efforts to defend human rights and fundamental freedom.

Sadly, infringements, abuse and persecution are still rife in the world, even half a century after Andrei Sakharov’s own battles to defend human rights in his home country.

Thankfully, though, it is by recognising the trials and tribulations of these silent millions that the European Parliament hopes to shine a very important spotlight on the pain that groups like the Uyghurs are going through on a daily basis.

And maybe, just maybe, we can all help make the new decade a better time for everyone to live in.