GUEST POST: A Look Back To When The French Army Invaded Gozo Through Ramla Bay

Following its 268-year sovereignty over the Maltese Islands, the Order of St John had, by 1798, reached a stage of irreversible decadence, in a world whose politics is no longer fuelled by religion but by reason, bringing its crusading ethos to nought by the mid-18th century, and thus its relevancy on the stage of European and Euro-Mediterranean politics.

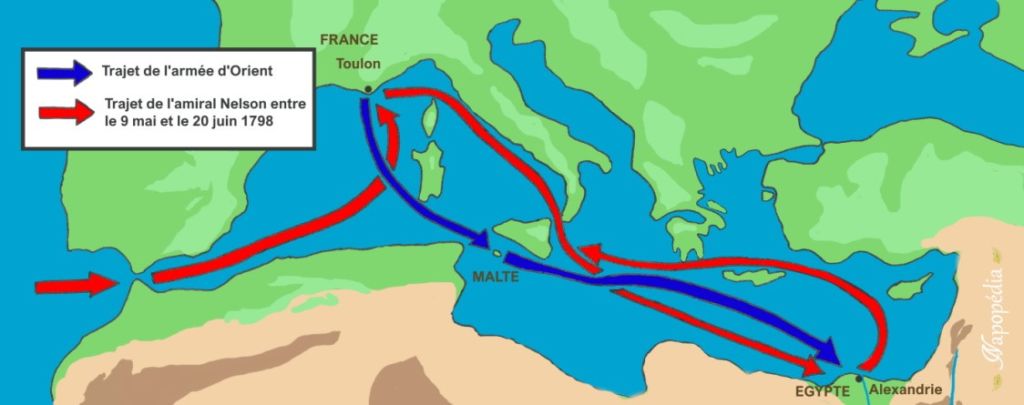

Departing from Toulon on 19th May 1798, and on his way to Egypt, in a bid to reach India and destroy Britain through economic warfare and attrition, Napoleon Bonaparte had made a stop in Malta on 10th June 1798 (still a general under the Republic at this time) to oust the anachronistic and aristocratic Order, and introduce Malta as a client state of the French Republic, imbibed with republican and revolutionary principles and laws.

With the Order refusing to formally surrender, Bonaparte’s Armee D’Orient (Army of the Orient/East) had conducted military landings across four points: St. Julian’s, Marsaxlokk, St. Paul’s Bay and Ramla on the sister island of Gozo (Malta is an archipelago made of three islands). As the larger of the three islands, and the administrative head, the island of Malta is prominently mentioned during these landings, however, the events concerning the island of Gozo are comparatively given little mention.

Here’s a look at the military landings of Gozo, at the beach of ‘Ramla’, as they had occurred on 10th June 1798.

A basic outline of the route taken by the French Navy/Army starting on 19 May 1798 (blue arrow)

The defences of Ramla Bay:

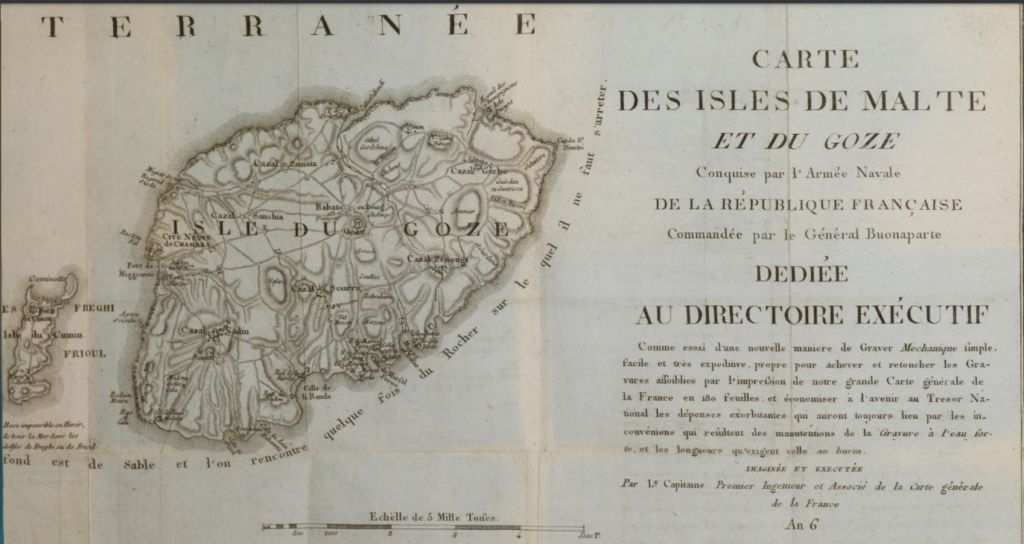

Of the two habitable islands (the third being the minuscule ‘Comino’), Gozo had a reputation of being the poorly defended of the two, having suffered its worst attack in 1551 when Barbary corsairs had landed and dragged its entire population into slavery.

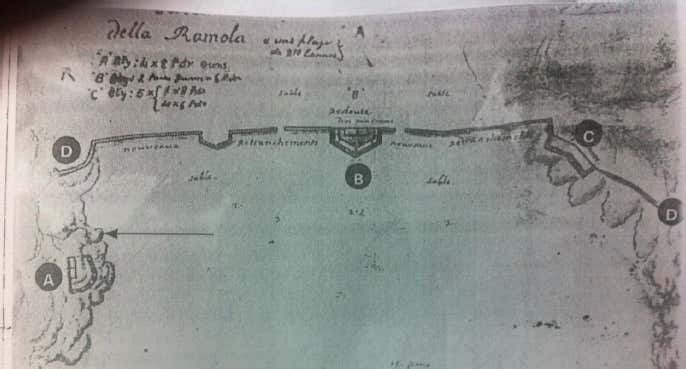

The bay of Ramla, situated on the north of the island, was always the favoured spot for enemy landings due to its fairly large and sandy beach, making it ideal for longboats and small ships to numerously conduct landings. The Order of St John had finally addressed the absence of defences on this beach in 1715, by constructing two; The Battery of ‘Belancourt’ (on the left-hand edge of the bay, also known as the Xaghra battery, due to it facing towards the direction of the village of Xaghra), the Battery of ‘Gironda’ (on the right-hand edge of the bay, also known as the Nadur battery, due to the same reasons), and the redoubt of ‘Vendome’ placed in the centre of the sandy shore. All three instalments were linked together with a defensive trench.1 Only the bare foundations of these batteries and the redoubt exist today.

In addition to the above, the mouth of the bay was fortified with an underwater sea wall; this was not however a wall to be understood in the literal and conventional sense, but rather a series of varying rocks and stones piled on one another to create a general semblance of a wall, enough to keep ships out from advancing.

There is mention of it being referred to as a “gettete di pietre” (“a throw of stones”). However, there are no longer any remains of this wall either; given its unsteady construction. It is believed to have easily been washed away by the currents ages ago.

The mouth of the bay was also protected by a ‘fougasse’, placed just below and to the side of the Gironda/Nadur battery. A ‘fougasse’ worked similar to a howitzer/mortar launcher; this was a (roughly) conical-shaped carving into a rock formation, filled with large quantities of gunpowder, followed by a collection of varying sizes of boulders. A soldier would light a fuse connecting to the gunpowder, sending these rocks and stones flying at an angle into the bay to damage any approaching vessels and wound invaders onboard.

An outline of Nadur’s defences: ‘A’ and ‘C’ denote Gironda and Belancourt batteries respectively, with B is the Vendome redoubt placed in the centre. The arrow points towards the ‘fougasse’ is placed. The above-mentioned trench is also seen here. (Source: https://www.academia.edu/3591456/Ir_Ramla_l_Hamra)

Napolean’s preparations

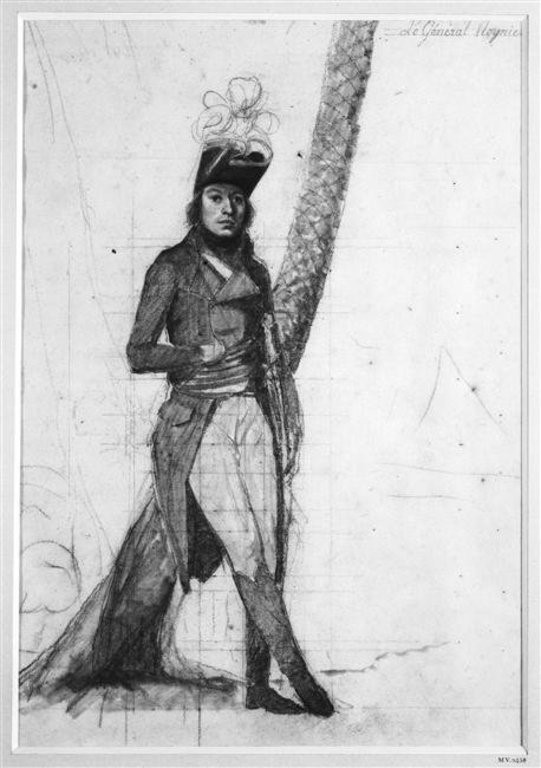

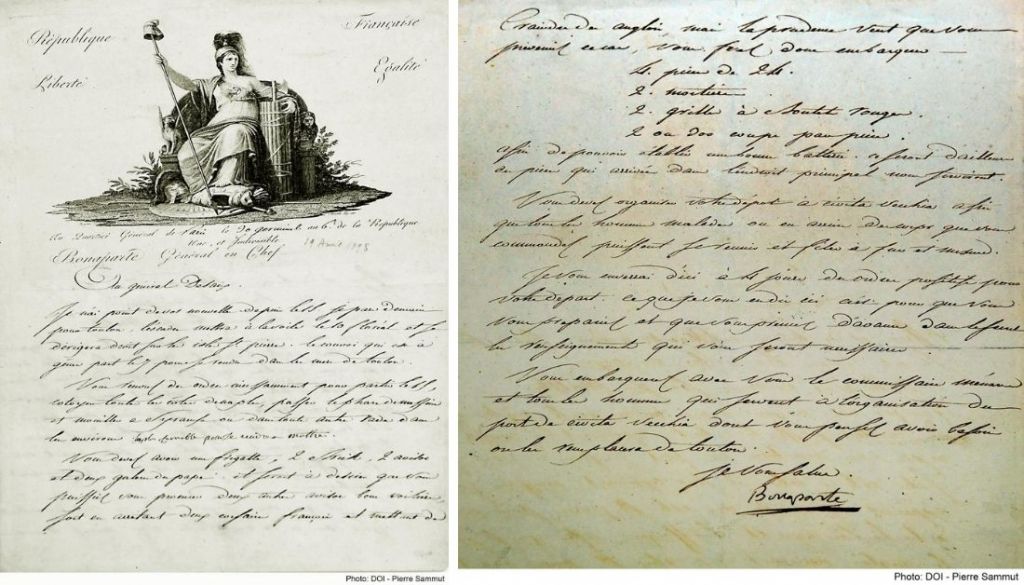

In conjunction with the other three landings on the main island of Malta, General Bonaparte, as head of the army, had drawn up his instructions for the landings at Gozo to General Berthier, his chief-of-staff. The orders, dated 9th June 1798, one day prior to the landings, were given to General Reynier and Admiral Brueys, through General Berthier, to form a convoy with the frigate L’Alceste as its flagship and scout the northern coasts of the island to determine a suitable landing spot:

“You will give the order, Citizen General (Berthier), to Admiral Brueys to bring the convoy around the frigate L’Alceste within reach of disembarking at the coast of La Ramla…If the Admiral thinks that the port of Miggiarro (Mgarr) is more advantageous for anchoring there… it will be able to replenish the convoy. He will put the command of the L’Alceste under the orders of General Reynier, and for everything related to the landing.”

Particular importance was given for Reynier to scout ‘Aain Rihanna’ (Ghajn Rihanna, today San Blas beach), Ramla bay, and some other spots, to determine the best landing spot for his incursion and to conduct himself in a way that will not alarm the inhabitants until the moment of disembarkation.

Further instructions by Bonaparte indicate that the landings were to be conducted ashore with the use of longboats, capable of carrying a number of troops, to the area deemed most appropriate by Reynier and not to allow for the disembarkation of more than the number of troops necessary to capture Gozo.

Following the capture of Gozo, a military commander was to be appointed for the island, the organization of a hospital with a hundred beds to cater for the Army’s sick. A company of artillerymen from the 4th demi-brigade were to stay on Gozo as part of the defence force (to man the existing guns along the coasts and those on the walls of the Citadella presumably).

A portrait of General Reynier in Egypt, sketched by Andre Dutertre in 1798 months, if not weeks, after having departed from Malta. Source: RMN-Grand Palais (Chateau de Versailles)

10th June 1798: The landing

A few sources have provided first-hand accounts of the landings which allowed for the successful capitulation of Gozo, from the Order of St John over the French army. These are derived from the first-hand accounts of General Reynier, and sources compiled by 19th-century scholar Clement de La Jonquiuere.

Reynier writes to Napoleon, on 13 June 1798, with a follow-up report and starts off with giving us an outline of the defences of the island of Gozo:

“This island was defended by a militia corps made up of inhabitants and formed into a regiment of musketeers of 800 men, a regiment of coast-guards of 1200 men, and in a company of 3008 including 30 mounted, in all 2300 men who were distributed over the different points of the coast, furnished with forts and batteries in all places of the northern part of the island.”

A portion of a map comprising of both Malta, Comino and Gozo, here depicting the second-half with Comino (far-left) and Gozo. The map is dated 1798 and shows all the towns, villages and fortifications (Ramla included). Taken from Louis de Laus de Boissy, Bonaparte Au Caire, ou memoirs sur l’expedition de ce General en Egypte published in 1799.

For an island with a population of 16,000 at this time9 and measuring 67 km², a force of 2,300 troops seems both excessively impressive. Following the instructions by Bonaparte, to determine a landing spot seemed most suitable for the landings, Reynier gives us his verdict on the matter:

“In order to avoid losing men and committing the first hostilities by landing near forts and [artillery] batteries, and so as not to expose the vessels to the [cannon] fires of the batteries; I looked for a point that was not guarded, and far away from the batteries, and I chose Redum-Kibir (Rdum il-Kbir), between the New Tower (Sopu Tower) and the first battery in Ramla’s bay (Gironda Battery).

“At this place, the shore is very steep and the inhabitants looked at it as safe from any offence. A passage that the waters have made in these rocks which border the shore could be used to climb heights.”

Reynier writes that currents drove the convoy away as far as four leagues (equating to about 22km) away from the coast. The morning of the day was spent rallying the convoy together, distributing the orders and approaching the coast once again.

Reynier moves to attack, with Rdum Il-Kbir as the landing point:

“At one o’clock in the afternoon he was with the Alceste and the convoy, eight to nine hundred toises from the shore12…I had troops embark in all the rowboats and I [Reynier] left from the Alceste along with the third company of grenadiers of the 85th demi-brigade… the bombards L’Etoile and Le Pluvier approached the land along with the rowboats; and as soon as the enemy saw the direction they were taking [towards Rdum Il-Kbir] they all ran there to fill up the heights. Hoping to arrive there likewise, I made oars.”

A letter written by Napoleon Bonaparte himself ordering one of his generals to invade Malta and Gozo.

Geoffrey Saint-Hilaire, one of the scientists accompanying the French army, who seems to have been present on the day, adds a gruesome detail: “A single, well-adjusted cannon shot broke a rudder [of a longboat] ; the shooting, which lasted half a quarter of an hour almost at close range and without our people being able to retaliate, killed a sergeant-major [of the Grenadiers] placed between General Reynier and my brother, as he wanted, and snatched out of importunity to be first to disembark.”

If interpreted by its literal sense, this can only mean that the Sergeant in question was unfortunate enough to be killed by a cannonball shot straight at and into him; a gruesome death which although unlucky would have occasionally happened during this era. Sources identify the Sergeant by only one name; Bertrand.

The 3rd company of Grenadiers eventually successfully disembarked at the base of the cliff:

Two hundred men lined the crest of the heights… and every moment this number increased.15 We climbed as quickly as possible, and almost without firing, despite the rapid slope formed by the landslides of earth and rocks, in spite of the fire of the enemies which plunged on them and the quarters of stone which they threw. Astonished, however, by the audacity of the grenadiers who always advanced despite the obstacles, they (Gozitan militia) fled. This fight was decided in a few minutes, and before any of the boats which followed had the chance to arrive.

Once the heights were secure, the grenadiers moved on to securing the “first” battery at Ramla17 which most likely refers to the Gironda battery, given its proximity to Rdum il-Kbir. No details on whether there was any fighting to take it, though it is likely for the defenders to have abandoned their post and fled also.

Aftermath

The brief assault resulted in the disarmament of the bay which allowed for the disembarkation of the rest of the invasion force to control the island. From here, one part of the force marched onto Fort Chambray to demand its capitulation. The other marched towards Rabat; the island’s administrative capital also containing a small citadel. By nightfall, both locations had capitulated.

A Captain of the engineers, Geoffroy, writes to General Reynier on the night of the 10th June from Rabat, a brief set of events concerning the march from Ramla up to Rabat, through the intermediary village of Xaghjra:

When you gave me the order to halt the companies of the 9th demi-brigade, to march on Sciarra (present-day Xaghjra), to arrange them in rows along the side of the road, I could only reach them once I reached at the heights of the city. Seeing how I could no longer halt the soldiers, I encouraged them to do the opposite and march forward to the village of Sciarra. As soon as he also sensed this, the General Lefebvre also ordered the men to march on, Lefebvre seized Sciarra, and established himself in the Church of the village, and from then protected himself with a line of observation posts. 18

By nightfall of the 10th, the island of Gozo was in possession of the French Republic. As was customary of the time, and following their surrender, the Knights commanding the overall defences of the island dined with their Revolutionary victors before their expulsion.

As with the inhabitants of the main island of Malta, the Gozitan inhabitants also enjoyed the many liberal ideals of the French revolution until relations soured into open rebellion in September 1798. The main citadel in Rabat fell by October to Maltese rebels, aided by British marines, along with the entire island.

The main island of Malta would however remain in a state of conflict against the French army stationed there for two years until September 1800.

Sources

https://www.academia.edu/3591456/Ir_Ramla_l_Hamra

Sir Hannibal Scicluna, Actes et documents pour servir à l’histoire de l’occupation française de Malte pendant les années 1798-1800 (Malta: Empire, 1932) (Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliotheque national de France)

Charles Savona Ventura, War and population change in the Maltese context, (https://www.um.edu.mt/umms/mmj/PDF/140.pdf)

Comte Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau, Histoire Generale de Napoleon Bonaparte Tome Premier (Paris: Ponthieu et Comp., 1827)

Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Lettres écrites d’Egypte à Cuvier, Jussieu, Lacépède, Monge, Desgenettes, Redouté jeune, Norry, etc., aux professeurs du Muséum et à sa famille (Paris:1901) (Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliotheque national de France)

Clement De La Jonquiere, L’Expedition D’Egypte 1798-1801 Tome 1er

Lovin Malta is open to external contributions that are well written and thought-provoking. If you would like your commentary to be featured as a guest post, please write to [email protected], add Guest Post in the subject line and attach a profile photo for us to use near your byline. Contributions are subject to editing and do not necessarily represent Lovin Malta’s views.

Share with a history buff!