A Look At Modernist Architecture In Malta

Being an inherently conservative nation, change was never something the Maltese took on willingly.

Baroque architecture was deeply rooted in the local architectural scene for several hundreds of years, making it very hard to replace the eloquent and grandiose architecture. With limited construction materials, construction techniques were scarcely challenged and change was not deemed necessary. Reinforced concrete was not a commonplace construction material until after the Second World War so construction was inadvertently limited to masonry walls and stone slabs coupled with steel or timber beams.

It was not until the late 1950s & 1960s after the postwar construction boom that several architects and artists were returning from their studies and work experiences overseas that change and architectural development started to happen on the island. English and Italian architecture magazines became commonplace at the Public Works Department and were undoubtedly a source of inspiration for the architecture which followed.

Project: White Rocks Complex - Photo Credit (Facebook): Nicky Farrugia

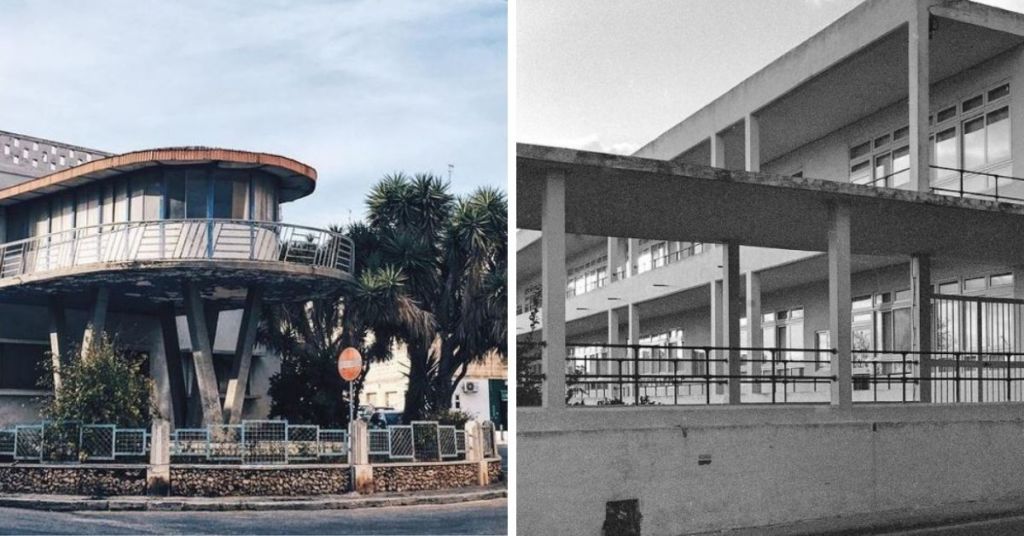

In 1964, when Malta sought independence from the British, the time was right to develop a new architectural language and this is when International Modernist Architecture really gained ground. The progressive and innovative language heavily influenced the design of a number of schools being built at the time. Change was seemingly invited and the younger architects at the Public Works fought hard to overcome the preconceived notions and ideas architecture had to fulfil.

Decoration was discarded, architecture became more honest and seemingly more brutal. Ornamentation was achieved through structural forms. Proportions, geometry, and composition were key. The architecture was focused on basic, fundamental principles; the penetration of natural light and cross ventilation.

Project: Villa Gauci, Gwardamanga - Photo Credit: Author; Project: Villa, Kappara - Photo Credit (Instagram): simonbernardgrech

The architectural concept and detailing did not stop at the facade but was taken through into the interiors of the space and shaped important design elements such as railings and doors. The advances in construction techniques allowed for new principles to come to play, larger openings allowed for larger expanses of glass to be integrated.

Whilst perhaps in isolation, this was not necessarily the best climatic decision, the play of light and shadow was a key component that so prompted the advent of cantilevered concrete shading structures and brise-soleil screens.

Project: Undulating concrete ceiling,Tal-Virtu Photo Credit (Instagram): davidfeliceap - Project: Semi-detached villa, Balzan - Photo Credit: Author

Concrete shell structures and curved forms were striking and exciting elements that were now made possible. The architecture fell servant to its surroundings and sought to integrate the natural environment on which it was to form part. An excellent example of this is Renato Laferla’s ‘school on stilts’ built to span over the existing Mall Gardens in Floriana. Nonetheless, much of Laferla’s work was also heavily criticised. The master found strong objection and public outcry but found backing in his contemporary Joseph Tonna who also worked at Public Works and very aptly wrote:

“Had man been content with the supreme achievements of Rheims, there would have been no Renaissance; had he been content with the Renaissance there would have been no Ronchamp. Whatever the heights achieved by a past style, there can be no justification for grafting it onto the buildings of another age, with another spirit pervading its social life, its scholarship, and its arts.” Sunday Times of Malta 17th April 1960 article by Joseph Tonna read.

Joseph G. Huntingford was given some liberty and freedom when he was sent to work in Gozo allowing the master par excellence the freedom to realise his dreams with little influence or obstruction from his superiors in Malta at the Public Works.

Project: Villa, Birkirkara - Photo Credit (Instagram): call_me_gwen; Project: Qala Primary School - Photo Credit (Instagram): markgmuscat

With time, experience and experimentation, the architecture looked upon vernacular architecture and therefore the local climatic considerations – Regionalism was founded. An example of this is the Manikata Church by Richard England, where references are drawn from the surrounding landscape and vernacular volumes found in nature together with prehistoric architectural forms. This period of high quality, timeless modernist architecture was short-lived and by the 1980s it was overrun by Post-Modernism.

Some of the best architectural masters to have ever graced our islands are the makers and founders of Modernist Architecture in Malta. Nonetheless, respect for these works is only very slowly garnering support and several of these architectural gems have already been raped. Public awareness has been made possible through the dedication of young individuals like Te fit-Tazza and Malta Doors.

Slowly the Planning Authority is also starting to issue protection status for some of the modernist properties which are still intact. It may not be too late to preserve what’s left but we need to act now and we need to act fast before a lot more of these gems fall into disrepair or into the hands of greedy developers.

Unfortunately, we have a long way to go in the urban planning of the country and although some pieces still stand they have been engulfed by mass development leaving them to stick out like a sore thumb.

Established in 2014, A Collective is a Maltese based architecture studio, aspiring to form a collaborative of creative and passionate individuals. This article is part of ongoing series with Te Fit-Tazza.

Lovin Malta is open to external contributions that are well written and thought-provoking. If you would like your commentary to be featured as a guest post, please write to [email protected], add Guest Post in the subject line and attach a profile photo for us to use near your byline.

What do you think of modernist architecture in Malta?