It’s Been 60 Years Since The Maltese Church Made Being Part Of The Labour Party A Sin

Last weekend marked the 60-year anniversary of the interdiction of the Executive Committee of Labour Party by the Maltese Catholic Church.

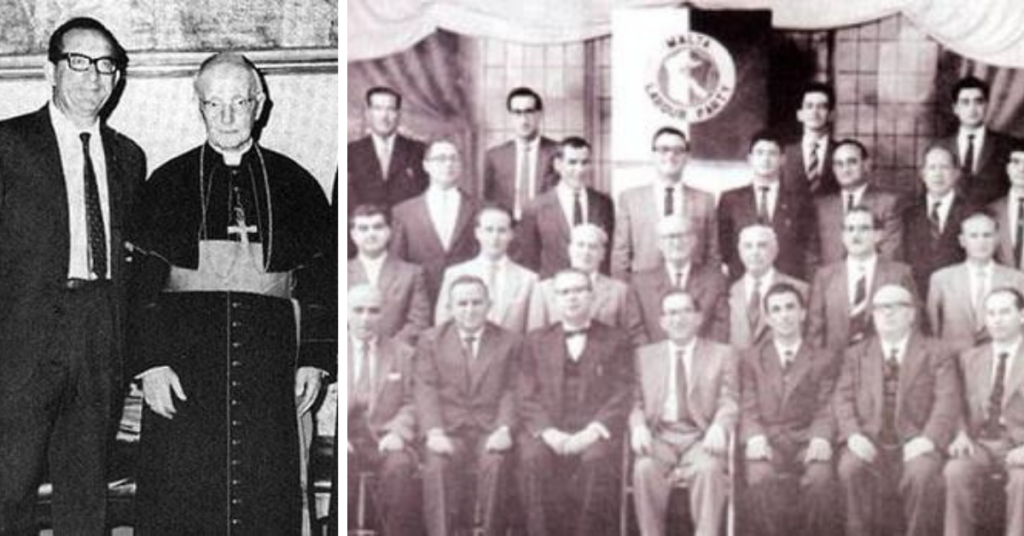

Back in April 1961, with the Maltese church convinced that the Malta Labour Party was becoming ever more communist, archbishop Michael Gonzi imposed an interdiction of the executive members of the Labour Party. This was then extended to all of the party’s activists and voters.

The event has been described as one of the last attempts by the church’s leadership to impose political power directly on the population and was largely driven by the rivalry between Gonzi and Labour leader Dom Mintoff, who was an advocate of the separation between church and state and who by that time had become had started to push for an independent and secular Malta.

Those who were interdicted were banned from receiving sacraments, in what was at the time a society dominated by religion and the church.

Those who died during this period were denied the right to be buried on consecrated ground, instead being buried in an unconsecrated part of the cemetery referred to as l-Miżbla (the dump). Several Labour Party officials, including Deputy Leader and highly-regarded author Ġużè Ellul Mercer, were among those buried in this way.

Some, like former Minister Joe Micallef Stafrace, who recently passed away, weren’t even allowed to get married in a church, instead having to do so in the sacristy.

Labourite weddings were often celebrated in English because they were considered to be “foreigners” with the newlyweds often being heckled by mobs.

Households known to belong to Labour supporters were often skipped by priests during Easter blessing. The country was quite literally torn apart.

The role the church played in every aspect of Maltese life at the time cannot be overstated.

The conflict had been years in the making with things finally coming to a head in April 1961 when the Labour Party declared that it would be willing to accept development assistance from any country.

This was interpreted as confirmation of the church’s fear that the Labour Party was inching closer to the Soviet Union and its style of communism.

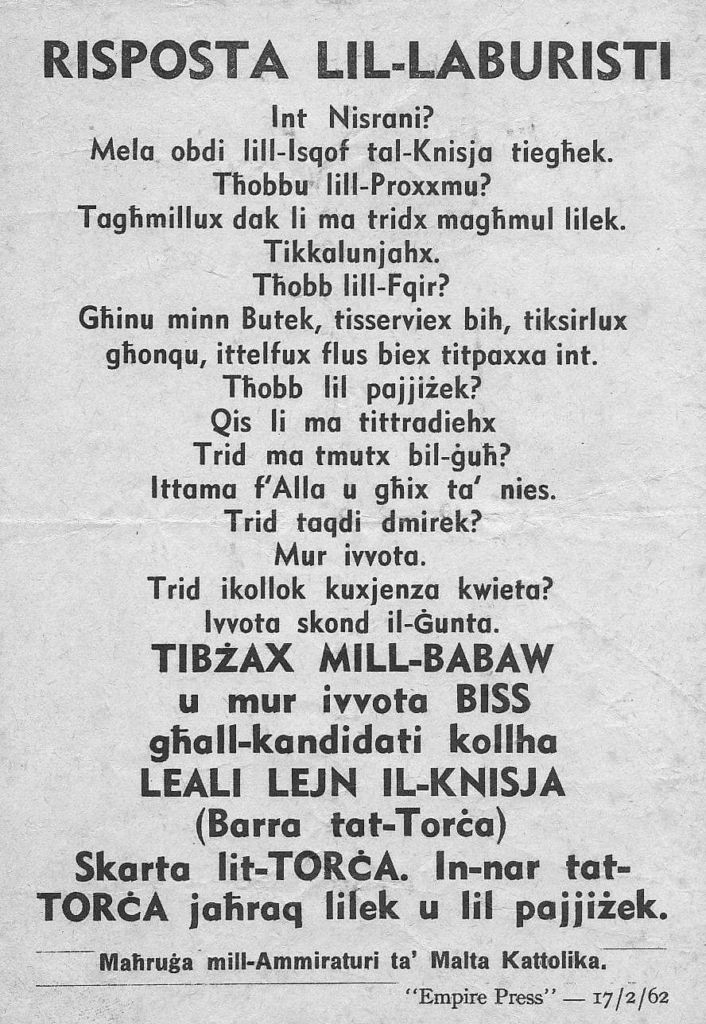

Members of the Labour Party Executive Committee were interdicted on 8th April 1961. Then, almost one month later, the church declared reading or selling socialist newspapers, attending Labour meetings, or voting for the party, a mortal sin.

The period was a tense and humiliating one for supporters of the Labour Party. Rallies were also often disrupted by continuous churchbells ringing and whistling and other deliberate noise by Catholic laypeople, while church sermons were predominately used to damn their political rivals.

The Labour Party did not win the 1962 election, though it still succeeded in garnering 33% of the vote, thanks to over 50,000 loyal supporters who came to be known as the ‘Suldati ta l-Azzar’ (soldiers of steel). Labour also lost the 1966 election before returning to power in 1971.

A formal peace agreement was reached on 4th April 1969 with the church declaring that it was wrong to impose mortal sin as political censure.

The agreement also made it clear that in a modern society it is necessary to make a distinction between the political community and the Church.

Two years ago, archbishop Charles J. Scicluna blessed the graves in which Ellul Mercer and other Labour politicians and activists were interred and finally apologised on behalf of the church and offered some closure to those victimised by the church’s actions.

Though it is now firmly in the past, the episode created deep divisions within Maltese society, many of which are still felt today.

Share this with someone who needs to read it.