Joseph Muscat’s Libel Case Against Facebook Fiend Will Test Malta’s Boundaries Of Speech On Social Media

The upcoming libel lawsuit filed by former Prime Minister Joseph Muscat against Facebook fiend Christian Grima is destined for media and political stardom.

It is the latest and most high-profile of a series of libel cases over posts or comments on Facebook, which has emerged as the main libel battleground after the overhaul of the Media and Defamation Act in 2018, which made it harder to target professional journalists with all types of libel, especially diversionary or vexatious libel suits.

It is telling, in this case, that Muscat announced the libel suit against Grima’s post in a Facebook post of his own. Grima, a lawyer who has built a following with his prolific, incendiary Facebook posts on local politics, retaliated with additional posts.

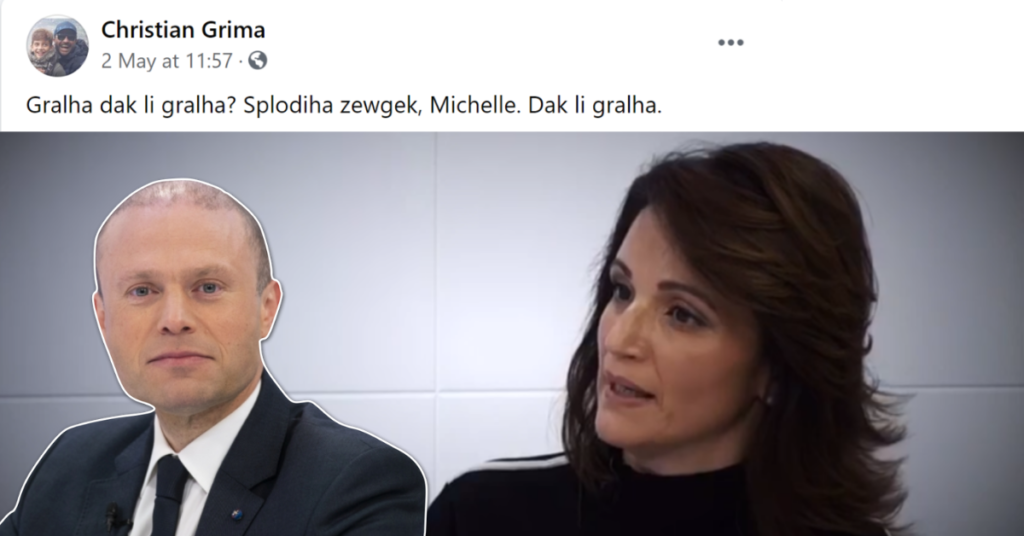

Muscat went for libel over a Facebook post in which Grima shared a link to a media interview of Muscat’s wife Michelle, adding a comment in reference to something uttered in the interview about ‘what happened to her’ – a reference to the assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia. Grima then wrote: “Your husband blew her up, Michelle. That is what happened to her.”

In a libel suit of this type – given that it is obvious to everyone in this country that Muscat didn’t literally blow up Caruana Galizia – Grima’s defence cannot be mounted on the basis of stating true facts. In libel cases, the onus is on the author to prove the accuracy of his statement and, failing that, the only other avenue of defence is to plead that the statement constitutes honest opinion or does not cause serious harm to the plaintiff.

These are two concepts that were introduced in the Media and Defamation Act of 2018, which is one of the more progressive legal reforms piloted by former Justice Minister Owen Bonnici, under pressure at the time to offer more legal protections to the media in the aftermath of Caruana Galizia’s assassination.

Honest opinion replaced the earlier concept of fair comment. Yet honest opinion – like fair comment before it – is not something you can just pluck out of thin air, it has to be an opinion or comment propped by facts.

In this case, it is a fact that Muscat did not take the action of triggering the bomb that killed Caruana Galizia.

However, Grima may plead that he was talking rhetorically, not literally, and that he was referring to the wider climate of impunity that reigned under Muscats’ premiership, the sense of political protection the assassins felt (as one of them recently testified in court), and the brotherly-like closeness between the man charged with commissioning the assassination, Yorgen Fenech, and Muscat’s trusted chief of staff, Keith Schembri – in this sense, Grima may argue that his statement constitutes an honest opinion.

It is at this point that the argument morphs into a test of the other concept of serious harm. The law specifies that libel, to be successful, has to “cause serious harm or are likely to seriously harm the reputation of the specific person or persons making the claim [for libel].”

Whether Grima’s statement, in particular, causes Muscat serious harm has to be considered in a context. That context is the societal dynamic surrounding the case, the particular medium – Facebook, which is more informal than professional media platforms – as well as Grima’s style.

Grima’s posts are written in a style that is stinging and grotesque – in that sense, it’s in the same vein of satire, which is allowed a measure of creative licence to offend and to mock. Grima’s followers are used to that style, and aware that his grotesque and incendiary posts are not necessarily the literal or factual truth, but a depiction of altered reality that’s more allegorical than factual.

All of this is likely to make Muscat’s libel struggle to pass the test of serious harm.

Yet two recent decisions by magistrate Rachel Montebello on Facebook posts offer little comfort to Grima. Montebello, who presides over the case involving Fenech, is one of the magistrates assigned libel cases, the other being Victor Axiak.

In a decree at the end of last year during criminal proceedings against Fenech, Montebello ordered contempt of court proceedings against the author of satirical website Bis-Serjeta for a satirical Facebook post on Fenech’s lawyers. The decree was intended to protect the lawyers as ‘officers of the court’, but senior legal sources told Lovin Malta that the provision of the law invoked was designed to protect court officials in their official duties, or at least lawyers during court proceedings, not lawyers featured in a satirical Facebook post.

The other case was brought by a member of parliament Rosianne Cutajar against two individuals, Rachel Williams and Godfrey Leone Ganado, over a Facebook comment that called the MP a “whore” (the comment was in Maltese: “Bil-Malti nghidu QAHBA”). The comment, written by Ganado under a post by Williams, arguably ought to have failed the test of serious harm.

Yet Cutajar prevailed, although Montebello did say that damages to be awarded would be “minimal” – €500 to be paid jointly by the two defendants. Most controversially, however, is the fact that Williams was found liable, even though she didn’t write the comment, simply for not having deleted the comment from her Facebook wall. In this sense, she was considered an editor of sorts responsible for comments on her wall.

The upcoming case, Joseph Muscat versus Christian Grima, will now serve as a fresh battleground for what Maltese courts consider fair or liable on social media.